The Invisible Building Blocks That Shape Our World

Have you ever wondered what makes up the screen you’re reading this on? Or why neon signs glow with distinct colors? The answer lies in the fascinating world of atoms – the fundamental building blocks of all matter around us. From the smartphone in your pocket to the stars twinkling in the night sky, everything is composed of these incredibly tiny particles that are too small to see even with the most powerful optical microscopes.

When you switch on a fluorescent tube light, witness the brilliant colors of fireworks, or see the aurora dancing across polar skies, you’re actually observing the behavior of atoms and their electrons. These phenomena, which seem almost magical, can be explained through the principles of atomic structure that we’ll explore in this chapter.

The study of atoms represents one of humanity’s greatest intellectual achievements. Just over a century ago, atoms were considered indivisible particles. Today, we understand their intricate internal structure, can manipulate individual atoms, and use this knowledge to create technologies like lasers, LED displays, and quantum computers that are revolutionizing our world.

This chapter will take you on a journey from the early philosophical ideas about atoms to the sophisticated quantum mechanical models that explain atomic behavior with remarkable precision. You’ll discover how scientists like Rutherford, Bohr, and others revolutionized our understanding of matter itself.

Learning Objectives: What You’ll Master in This Chapter

By the end of this comprehensive study guide, you will be able to:

- Understand the historical development of atomic models and their limitations

- Explain Rutherford’s alpha particle scattering experiment and its groundbreaking conclusions

- Master Bohr’s model of the hydrogen atom and its postulates

- Calculate energy levels, radii, and frequencies in hydrogen-like atoms

- Analyze atomic spectra and understand the origin of spectral lines

- Solve numerical problems involving atomic transitions and energy calculations

- Connect atomic structure to real-world applications in technology and nature

- Prepare effectively for CBSE Board exam questions on atomic physics

Section 1: The Quest to Understand Atoms – Historical Development

Early Atomic Concepts

The concept of atoms isn’t new – it dates back over 2,400 years to ancient Greek philosophers like Democritus, who proposed that matter consists of indivisible particles called “atomos” (meaning “uncuttable”). However, these were purely philosophical ideas without experimental evidence.

The scientific study of atoms began in earnest during the 19th century. John Dalton’s atomic theory (1803) provided the first scientific framework, proposing that elements consist of identical atoms and compounds form through definite combinations of different atoms. This theory successfully explained the laws of chemical combination but treated atoms as solid, indivisible spheres.

Physics Check: Can you explain why Dalton’s model was revolutionary for its time, even though we now know it’s incomplete? Consider how it explained the law of conservation of mass and definite proportions.

Thomson’s “Plum Pudding” Model

The discovery of the electron by J.J. Thomson in 1897 shattered the idea of indivisible atoms. Thomson’s cathode ray tube experiments revealed that atoms contain negatively charged particles much lighter than atoms themselves. This led to his “plum pudding” model (1904), where atoms were imagined as spheres of positive charge with electrons embedded within, like raisins in a pudding.

[INSERT DIAGRAM: Thomson’s plum pudding model showing a sphere of positive charge with embedded electrons, alongside his cathode ray tube experimental setup]

Thomson’s model successfully explained:

- The electrical neutrality of atoms

- The formation of ions through electron gain or loss

- Basic chemical bonding concepts

However, it couldn’t explain the stability of atoms or the characteristic spectra emitted by different elements.

The Revolutionary Alpha Particle Scattering Experiment

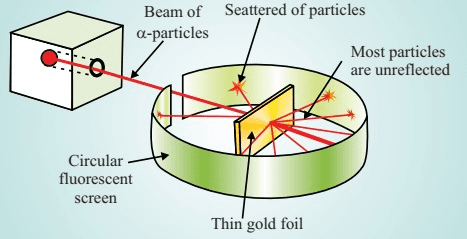

Everything changed in 1909 when Ernest Rutherford, along with his students Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, conducted one of the most important experiments in physics history. They fired alpha particles (helium nuclei) at a thin gold foil and observed their scattering patterns.

Real-World Physics: Alpha particles are still used today in smoke detectors! The americium-241 source emits alpha particles that ionize air molecules, creating a small current. When smoke particles enter the chamber, they disrupt this current, triggering the alarm.

The experimental setup involved:

- A radioactive source emitting alpha particles

- A thin gold foil (only a few atoms thick)

- A fluorescent screen to detect scattered alpha particles

- A moveable detector to measure scattering at different angles

Section 2: Rutherford’s Nuclear Model – A Paradigm Shift

Unexpected Results That Changed Physics

If Thomson’s model were correct, the massive alpha particles should have passed through the gold foil with minimal deflection, like bullets through tissue paper. Instead, Rutherford’s team observed:

- Most alpha particles passed straight through (about 98%)

- Some were deflected at small angles (less than 1%)

- A tiny fraction bounced back (about 1 in 8,000)

Rutherford famously described his surprise: “It was almost as incredible as if you fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you.”

The Nuclear Model Emerges

To explain these results, Rutherford proposed a revolutionary model in 1911:

- The atom is mostly empty space (explaining why most alpha particles passed through)

- A tiny, dense, positively charged nucleus sits at the center (explaining the rare large-angle scattering)

- Electrons orbit the nucleus at relatively large distances (maintaining electrical neutrality)

Problem-Solving Strategy: When analyzing scattering experiments, always consider the relative sizes and charges of the particles involved. The impact parameter (closest approach distance) determines the scattering angle.

Mathematical Analysis of Scattering

The scattering of alpha particles follows a specific mathematical relationship. For an alpha particle with kinetic energy E approaching a nucleus with atomic number Z:

[EQUATION: Closest approach distance: r₀ = (2kZe²)/(4πε₀E)]

Where:

- k = Coulomb’s constant

- Z = atomic number of target nucleus

- e = elementary charge

- ε₀ = permittivity of free space

- E = kinetic energy of alpha particle

For gold (Z = 79) and typical alpha particles (E ≈ 5 MeV), this gives r₀ ≈ 10⁻¹⁴ m, much smaller than atomic dimensions (≈ 10⁻¹⁰ m).

Common Error Alert: Students often confuse the distance of closest approach with the nuclear radius. The closest approach distance represents the point where the alpha particle momentarily stops before being repelled, not the actual size of the nucleus.

Section 3: Limitations of Rutherford’s Model and the Path to Bohr

The Stability Problem

Despite its success in explaining scattering experiments, Rutherford’s model faced a fundamental problem from classical physics. According to Maxwell’s electromagnetic theory, any accelerating charged particle must radiate energy. Since electrons in circular orbits are constantly accelerating (centripetal acceleration), they should:

- Continuously radiate electromagnetic energy

- Spiral into the nucleus in about 10⁻⁸ seconds

- Emit a continuous spectrum of radiation

This prediction contradicted two key observations:

- Atoms are stable and exist for indefinite periods

- Atoms emit discrete spectral lines, not continuous spectra

Spectral Evidence

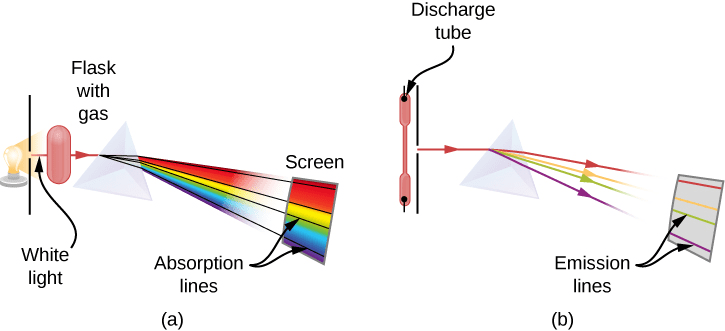

When atoms are excited (by heating or electrical discharge), they emit light with very specific wavelengths characteristic of each element. This creates line spectra rather than continuous spectra, providing a unique “fingerprint” for each element.

Real-World Physics: This principle enables astronomers to determine the composition of distant stars and galaxies by analyzing their spectra. The same technique helps identify elements in crime scene analysis and quality control in manufacturing.

The Hydrogen Spectrum

Hydrogen, being the simplest atom, provided the clearest spectral evidence. The visible lines of hydrogen (Balmer series) follow a precise mathematical pattern discovered by Johann Balmer in 1885:

[EQUATION: Balmer Formula: 1/λ = R∞(1/2² – 1/n²)] where n = 3, 4, 5, …

Where R∞ is the Rydberg constant (1.097 × 10⁷ m⁻¹) and λ is the wavelength of emitted light.

This empirical formula worked perfectly but had no theoretical explanation until Bohr’s revolutionary model.

Section 4: Bohr’s Model – Quantum Meets Classical Physics

The Quantum Leap

In 1913, Niels Bohr made a bold assumption that combined classical physics with Planck’s new quantum theory. He proposed that electrons in atoms exist in specific, quantized energy levels, revolutionizing our understanding of atomic structure.

Bohr’s Fundamental Postulates

Postulate 1: Quantized Orbits

Electrons revolve around the nucleus in circular orbits, but only certain orbits are allowed. These orbits correspond to specific energy levels where the electron does not radiate energy.

Postulate 2: Angular Momentum Quantization

The angular momentum of an electron in an allowed orbit is quantized:

[EQUATION: L = mvr = nħ = n(h/2π)]

Where:

- L = angular momentum

- m = electron mass

- v = orbital velocity

- r = orbital radius

- n = principal quantum number (1, 2, 3, …)

- ħ = reduced Planck constant

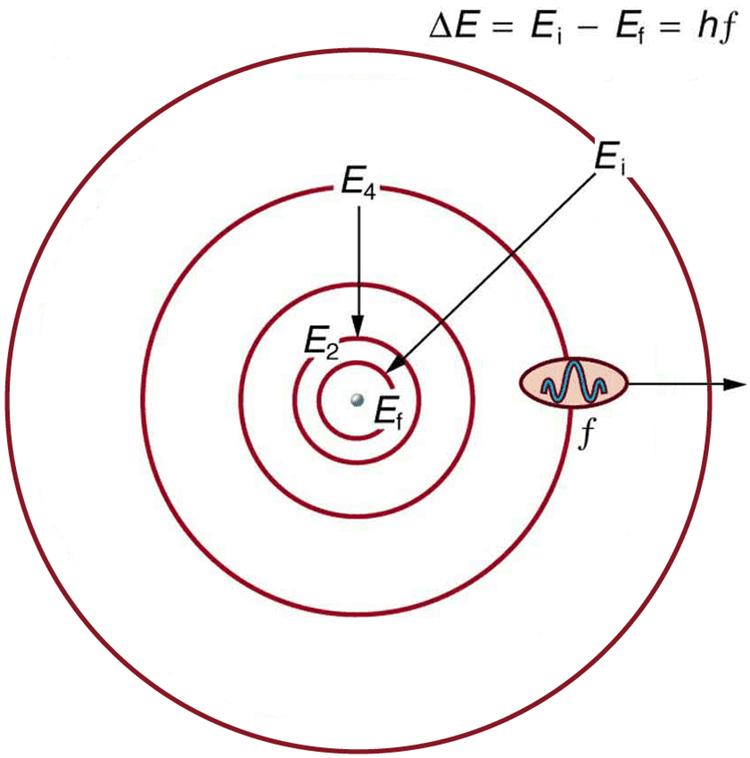

Postulate 3: Quantum Transitions

When an electron jumps between energy levels, it emits or absorbs a photon with energy equal to the difference between the levels:

[EQUATION: E_photon = hf = E_final – E_initial]

Deriving the Bohr Model

Let’s derive the key relationships for hydrogen-like atoms step by step.

For a circular orbit, the centripetal force equals the electrostatic force:

[EQUATION: mv²/r = ke²/r²]

From the angular momentum quantization:

[EQUATION: mvr = nħ, so v = nħ/(mr)]

Substituting into the force equation:

[EQUATION: m(nħ/mr)²/r = ke²/r²]

Solving for the orbital radius:

[EQUATION: r_n = n²ħ²/(mke²) = n²a₀]

Where a₀ = ħ²/(mke²) = 0.529 × 10⁻¹⁰ m is the Bohr radius.

Physics Check: Notice how the orbital radius increases as n². This means the electron in the fourth energy level (n=4) is 16 times farther from the nucleus than in the ground state (n=1).

Energy Levels in Hydrogen

The total energy of an electron in the nth orbit is:

[EQUATION: E_n = -13.6/n² eV]

The negative sign indicates that the electron is bound to the nucleus. Higher energy levels (larger n) have less negative energies, approaching zero as n → ∞ (ionization).

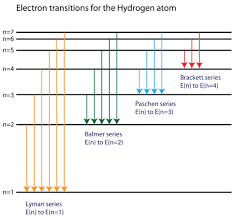

Spectral Series Explained

Bohr’s model beautifully explained the hydrogen spectrum. Different series correspond to transitions ending at different energy levels:

- Lyman Series (UV): Transitions to n=1

- Balmer Series (Visible): Transitions to n=2

- Paschen Series (IR): Transitions to n=3

- Brackett Series (IR): Transitions to n=4

The general formula becomes:

[EQUATION: 1/λ = R∞(1/n₁² – 1/n₂²)]

Where n₁ < n₂ and R∞ = mke⁴/(8ε₀²h³c) = 1.097 × 10⁷ m⁻¹

Historical Context: Bohr’s successful derivation of the Rydberg constant from fundamental physical constants was considered one of the greatest triumphs in theoretical physics, earning him the Nobel Prize in 1922.

Section 5: Problem-Solving with Bohr’s Model

Systematic Problem-Solving Framework

When solving Bohr model problems, follow these steps:

- Identify the given information (initial state, final state, element)

- Determine what you need to find (wavelength, frequency, energy, etc.)

- Choose appropriate equations based on the problem type

- Apply conservation principles (energy, angular momentum)

- Check units and reasonableness of your answer

Energy Transition Calculations

Example Problem 1: Calculate the wavelength of light emitted when a hydrogen electron transitions from n=4 to n=2.

Solution:

Step 1: Find the energy change

E₄ = -13.6/4² = -0.85 eV

E₂ = -13.6/2² = -3.4 eV

ΔE = E₄ – E₂ = -0.85 – (-3.4) = 2.55 eV

Step 2: Convert to joules

ΔE = 2.55 eV × 1.6 × 10⁻¹⁹ J/eV = 4.08 × 10⁻¹⁹ J

Step 3: Find wavelength using E = hf = hc/λ

λ = hc/ΔE = (6.63 × 10⁻³⁴ × 3 × 10⁸)/(4.08 × 10⁻¹⁹) = 487 nm

This wavelength corresponds to blue-green light in the visible spectrum (Balmer series).

Orbital Radius and Velocity Calculations

Example Problem 2: Find the radius and velocity of an electron in the third energy level of hydrogen.

Solution:

Step 1: Calculate radius

r₃ = 3² × a₀ = 9 × 0.529 × 10⁻¹⁰ m = 4.76 × 10⁻¹⁰ m

Step 2: Calculate velocity using v = nħ/(mr)

v₃ = 3 × 1.055 × 10⁻³⁴/(9.11 × 10⁻³¹ × 4.76 × 10⁻¹⁰) = 7.3 × 10⁵ m/s

Common Error Alert: Remember that orbital velocity decreases with increasing n, even though the electron has higher total energy. This is because potential energy increases more than kinetic energy decreases.

Section 6: Advanced Applications and Extensions

Hydrogen-like Ions

Bohr’s model extends to hydrogen-like ions (single electron systems like He⁺, Li²⁺, Be³⁺). The key modification is including the nuclear charge Z:

[EQUATION: E_n = -13.6Z²/n² eV]

[EQUATION: r_n = n²a₀/Z]

This explains why helium ions emit higher energy photons than hydrogen atoms.

Ionization Energy

The ionization energy is the minimum energy required to remove an electron from the ground state:

For hydrogen: E_ionization = 0 – (-13.6) = 13.6 eV

Real-World Physics: Understanding ionization energies is crucial for plasma physics, used in fusion reactors and plasma displays. Different elements require different energies to create and maintain plasma states.

Limitations of Bohr’s Model

Despite its successes, Bohr’s model has limitations:

- Only works for hydrogen-like atoms

- Cannot explain fine structure of spectral lines

- Doesn’t account for electron spin

- Contradicts the uncertainty principle

- Cannot predict intensities of spectral lines

These limitations led to the development of quantum mechanics in the 1920s.

Section 7: Experimental Verification and Modern Applications

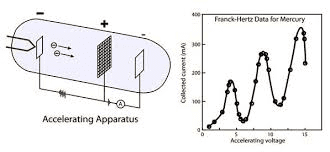

Franck-Hertz Experiment

In 1914, James Franck and Gustav Hertz provided direct experimental evidence for quantized energy levels. They fired electrons through mercury vapor and measured the energy loss of electrons at specific voltages.

The experiment showed that electrons lose energy only in specific amounts (4.9 eV for mercury), confirming Bohr’s quantized energy levels.

Laser Technology

Modern laser technology depends directly on the principles discovered through atomic physics:

- Population Inversion: Creating more atoms in excited states than ground states

- Stimulated Emission: Photons triggering identical photons from excited atoms

- Coherent Light: All photons have the same wavelength and phase

Real-World Physics: From barcode scanners to surgical procedures, from fiber optic communications to DVD players, lasers based on atomic transitions are everywhere in modern technology.

Atomic Clocks

The most precise timekeeping devices use atomic transitions. Cesium atomic clocks measure time based on the microwave radiation emitted when cesium atoms transition between energy levels. These clocks are accurate to one second in 30 million years!

Section 8: Laboratory Investigations and Experimental Skills

Spectroscopy Experiments

Understanding atomic structure requires hands-on experience with spectral analysis:

Equipment Needed:

- Discharge tubes containing various gases

- High-voltage power supply

- Spectroscope or diffraction grating

- Wavelength measurement tools

Procedure:

- Excite gas atoms using electrical discharge

- Observe emitted light through spectroscope

- Measure wavelengths of prominent lines

- Compare with known atomic spectra

- Identify elements based on spectral fingerprints

Data Analysis:

- Calculate frequencies from measured wavelengths

- Determine energy differences between levels

- Verify relationships predicted by Bohr’s model

Error Analysis in Atomic Measurements

Common sources of error in spectroscopy:

- Instrumental Resolution: Spectroscope limitations

- Temperature Effects: Doppler broadening of lines

- Pressure Broadening: Collision effects in gas discharge

- Calibration Errors: Reference wavelength uncertainties

Problem-Solving Strategy: Always consider significant figures based on instrumental precision. Wavelength measurements typically have uncertainties of ±1 nm with school spectroscopes.

Designing Controlled Experiments

When investigating atomic properties:

- Control variables: temperature, pressure, voltage

- Measure systematically across ranges

- Use appropriate control groups

- Account for environmental factors

- Repeat measurements for statistical reliability

Section 9: Practice Problems – Mastering Atomic Calculations

Multiple Choice Questions

Question 1: In Rutherford’s alpha particle scattering experiment, what fraction of alpha particles were deflected by more than 90°?

A) About 50%

B) About 10%

C) About 1%

D) About 0.01%

Answer: D) About 0.01% (1 in 8,000)

Explanation: The vast majority of alpha particles passed through with little deflection, demonstrating that atoms are mostly empty space. Only a tiny fraction encountered the dense nucleus directly.

Question 2: According to Bohr’s model, the angular momentum of an electron in the nth orbit is:

A) nh

B) nħ

C) n²ħ

D) ħ/n

Answer: B) nħ, where ħ = h/2π

Question 3: The wavelength of the first line in the Balmer series of hydrogen is approximately:

A) 486 nm

B) 656 nm

C) 434 nm

D) 410 nm

Answer: B) 656 nm (corresponding to the n=3 to n=2 transition)

Free Response Problems with Complete Solutions

Problem 1: A hydrogen atom absorbs a photon and its electron moves from n=1 to n=3. Calculate:

a) The energy of the absorbed photon

b) The wavelength of the photon

c) The region of electromagnetic spectrum

Solution:

a) Energy calculation:

E₁ = -13.6/1² = -13.6 eV

E₃ = -13.6/3² = -1.51 eV

ΔE = E₃ – E₁ = -1.51 – (-13.6) = 12.09 eV

b) Wavelength calculation:

E = hf = hc/λ

λ = hc/E = (4.14 × 10⁻¹⁵ eV·s × 3 × 10⁸ m/s)/(12.09 eV)

λ = 1.03 × 10⁻⁷ m = 103 nm

c) This wavelength is in the ultraviolet region (Lyman series).

Problem 2: Calculate the radius and velocity of an electron in the second Bohr orbit of a Li²⁺ ion (Z=3).

Solution:

For hydrogen-like ions: r_n = n²a₀/Z

r₂ = (2²)(0.529 × 10⁻¹⁰ m)/3 = 7.05 × 10⁻¹¹ m

For velocity: v = Zke²/(nħ)

v₂ = (3)(2.18 × 10⁶ m/s)/2 = 3.27 × 10⁶ m/s

(Note: 2.18 × 10⁶ m/s is the velocity in the first Bohr orbit of hydrogen)

Data Analysis Problems

Problem 3: The following wavelengths were observed in the Balmer series of hydrogen:

- 656.3 nm (red)

- 486.1 nm (blue-green)

- 434.0 nm (blue)

- 410.2 nm (violet)

Determine which transitions these correspond to and verify using Bohr’s model.

Solution:

Using the Balmer formula: 1/λ = R∞(1/4 – 1/n²) where n ≥ 3

For 656.3 nm: 1/λ = 1.524 × 10⁶ m⁻¹

1.097 × 10⁷(1/4 – 1/n²) = 1.524 × 10⁶

Solving: n = 3 (transition 3→2)

Similarly:

- 486.1 nm corresponds to n=4→2

- 434.0 nm corresponds to n=5→2

- 410.2 nm corresponds to n=6→2

The calculated wavelengths match experimental values within measurement uncertainty.

Experimental Design Questions

Question: Design an experiment to measure the ionization energy of hydrogen atoms. Include equipment needed, procedure, data analysis methods, and potential sources of error.

Answer Framework:

- Equipment: High-energy photon source (UV/X-ray), hydrogen gas sample, photoelectron spectrometer, energy analyzer

- Procedure: Irradiate hydrogen with photons of known energy, measure kinetic energy of ejected electrons

- Analysis: Use Einstein’s photoelectric equation: E_photon = Ionization Energy + KE_electron

- Error Sources: Instrumental resolution, photon energy uncertainty, electron scattering effects

Section 10: Exam Preparation Strategies

High-Frequency Topics in CBSE Exams

Based on exam analysis, focus your preparation on:

- Rutherford’s scattering experiment (conceptual understanding and conclusions)

- Bohr’s postulates and their applications to hydrogen spectrum

- Energy level calculations and transitions between levels

- Wavelength/frequency calculations for spectral series

- Radius and velocity calculations for Bohr orbits

- Hydrogen-like ion modifications (effect of nuclear charge)

Problem-Solving Time Management

For numerical problems:

- Simple calculations (2-3 marks): 3-4 minutes

- Multi-step problems (5 marks): 8-10 minutes

- Derivations (3-5 marks): 6-8 minutes

Exam Tip: Always write the relevant formula first, substitute values with units, and box your final answer with appropriate significant figures.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Unit Conversions: Always convert eV to joules when using SI formulas

- Sign Conventions: Energy levels are negative; energy differences are positive when emitting photons

- Quantum Numbers: Remember n starts from 1, not 0

- Formula Selection: Use the correct form for hydrogen-like ions (include Z factor)

- Significant Figures: Match precision to given data (usually 3 significant figures)

Common Error Alert: Many students forget that the Bohr radius formula gives the radius for hydrogen (Z=1). For other hydrogen-like ions, divide by Z.

Memory Aids and Relationships

Key Constants to Remember:

- Bohr radius: a₀ = 0.529 × 10⁻¹⁰ m

- Hydrogen ground state energy: E₁ = -13.6 eV

- Rydberg constant: R∞ = 1.097 × 10⁷ m⁻¹

- Speed of light: c = 3 × 10⁸ m/s

- Planck’s constant: h = 6.63 × 10⁻³⁴ J·s = 4.14 × 10⁻¹⁵ eV·s

Useful Relationships:

- Energy scales as 1/n²

- Radius scales as n²

- Frequency ∝ Z²/n³ (for transitions)

Practice Schedule Recommendations

3 weeks before exam:

- Review theory and derivations (1 hour daily)

- Solve 5-10 numerical problems daily

- Focus on conceptual understanding

1 week before exam:

- Solve previous year questions under timed conditions

- Review common formulas and constants

- Practice drawing energy level diagrams quickly

Final revision:

- Quick formula review (30 minutes)

- Solve 2-3 challenging problems

- Review common mistakes checklist

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Mastery Checklist

You’ve successfully mastered CBSE Class 12 Physics Chapter 12 – Atoms when you can:

✓ Explain the historical development and limitations of atomic models

✓ Describe Rutherford’s experiment and interpret its results

✓ State and apply Bohr’s postulates to solve numerical problems

✓ Calculate wavelengths, frequencies, and energies for atomic transitions

✓ Analyze spectral data and identify corresponding energy level transitions

✓ Solve problems involving hydrogen-like ions with nuclear charge Z

✓ Connect atomic structure concepts to real-world applications

✓ Approach exam questions systematically with proper problem-solving techniques

Connections to Other Physics Units

The atomic structure concepts you’ve learned connect directly to:

- Chapter 11 (Dual Nature of Matter): De Broglie wavelengths and electron behavior

- Chapter 13 (Nuclei): Nuclear physics and radioactive decay

- Chapter 14 (Semiconductor Electronics): Energy bands and electronic devices

- Modern Physics Applications: Quantum mechanics, laser technology, medical imaging

Bridge to Advanced Studies

If you’re planning to pursue physics or engineering, this chapter provides the foundation for:

- Quantum mechanics and wave functions

- Molecular physics and chemical bonding

- Solid state physics and materials science

- Nuclear and particle physics

- Quantum technologies and computing

Real-World Impact

The principles you’ve studied enable technologies that define modern life:

- Medical Imaging: MRI and PET scans use atomic physics principles

- Communication: Fiber optics and satellite communications rely on laser technology

- Computing: Quantum computers may revolutionize information processing

- Energy: Understanding fusion requires knowledge of atomic structure

- Materials: Nanotechnology manipulates matter at the atomic scale

Final Thought: The journey from philosophical speculation about “atomos” to precise quantum mechanical descriptions represents one of humanity’s greatest intellectual achievements. You’re now part of this continuing story, equipped with the knowledge to understand and contribute to our evolving understanding of the universe’s fundamental building blocks.

Study Resources and Next Steps

Recommended Practice:

- NCERT exemplar problems for additional challenging questions

- Previous 10 years’ CBSE question papers for exam pattern familiarity

- Online simulations for visualizing atomic models and transitions

- Laboratory experiments with spectroscopes when available

Further Exploration:

- Research current developments in atomic physics

- Explore applications in quantum computing and nanotechnology

- Investigate how atomic clocks enable GPS technology

- Study the role of spectroscopy in astronomical discoveries

Remember, mastering atomic physics isn’t just about passing an exam – it’s about understanding the fundamental nature of reality itself. The concepts you’ve learned provide a window into the quantum world that governs everything from the behavior of electrons in your smartphone to the nuclear fusion powering the Sun.

Keep questioning, keep exploring, and let your curiosity about the atomic world drive your continued learning journey in physics and beyond.

This comprehensive study guide represents current CBSE curriculum standards and incorporates the latest understanding of atomic physics. Regular practice with these concepts and problems will ensure your success in board examinations and provide a solid foundation for advanced physics studies.

Recommended –

1 thought on “Atoms Class 12 Notes: NCERT Solutions, Atomic Models & Important Questions for CBSE Board Exams”