The Revolutionary Science Shaping Our World

Imagine walking into your local pharmacy and picking up human insulin that was produced by bacteria, or eating vegetables that have been genetically modified to resist pests and provide better nutrition. Perhaps you’ve heard of COVID-19 vaccines developed using cutting-edge genetic engineering techniques, or witnessed how DNA fingerprinting helps solve criminal cases on television. These aren’t scenes from a science fiction movie – they’re everyday realities made possible by biotechnology.

Biotechnology represents one of the most exciting and rapidly evolving fields in modern biology. It’s the science that allows us to harness living organisms and their cellular components to develop products and processes that benefit humanity. From the insulin that saves diabetic lives to the genetically modified crops that feed millions, biotechnology bridges the gap between laboratory discoveries and real-world solutions.

As a Class 12 biology student, you’re about to embark on a fascinating journey through the molecular machinery that makes life tick. You’ll discover how scientists can cut and paste DNA like text in a document, how bacteria can be transformed into living factories, and how the same principles that govern natural genetic processes can be manipulated to solve human problems.

This chapter isn’t just about memorizing processes and terminology – it’s about understanding the fundamental principles that are revolutionizing medicine, agriculture, and industry. Whether you’re preparing for your CBSE board exams or planning a career in biotechnology, this comprehensive guide will provide you with the deep understanding and practical knowledge you need to excel.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this study guide, you will be able to:

- Understand the fundamental principles of genetic engineering and biotechnology

- Explain the structure and function of key tools used in biotechnology, including restriction enzymes, vectors, and host organisms

- Describe the process of recombinant DNA technology from gene isolation to protein production

- Analyze the steps involved in gene cloning and the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

- Evaluate different cloning vectors and their specific applications

- Apply biotechnology principles to solve real-world problems in medicine, agriculture, and industry

- Critically assess the ethical implications and biosafety concerns of genetic engineering

- Connect biotechnology concepts to current research and emerging technologies

- Demonstrate practical knowledge through experimental design and data analysis

- Prepare effectively for CBSE board examinations and competitive entrance tests

1: Foundations of Biotechnology – Understanding the Molecular Revolution

What Makes Biotechnology Possible?

Biotechnology didn’t emerge overnight. It’s built on decades of fundamental discoveries about how life works at the molecular level. Think of it as a sophisticated toolkit that allows scientists to read, edit, and rewrite the genetic instructions that control all living things.

The foundation of modern biotechnology rests on several key discoveries. First, scientists learned that all living organisms use the same genetic code – the same DNA language whether you’re looking at a bacterium, a plant, or a human being. This universality means that a human gene can function in a bacterial cell, and vice versa. It’s like discovering that all computers in the world use the same programming language, making it possible to transfer software between different machines.

Second, researchers discovered enzymes that could cut DNA at specific sequences, like molecular scissors with incredible precision. These restriction enzymes, combined with other enzymes that could paste DNA fragments together, gave scientists the ability to manipulate genetic material with surgical accuracy.

Biology Check: Can you explain why the universality of the genetic code is crucial for biotechnology applications?

The Central Dogma and Biotechnology Applications

Remember the central dogma of molecular biology: DNA → RNA → Protein. This fundamental principle underlies every biotechnology application. When we insert a human insulin gene into bacteria, we’re relying on the bacterial machinery to transcribe that DNA into RNA and translate it into functional human insulin protein.

Understanding this flow of genetic information helps explain why biotechnology works across species boundaries. A gene is essentially a recipe written in DNA, and as long as the host organism can read that recipe (which most can, thanks to the universal genetic code), it can produce the desired protein.

Real-World Biology: The human insulin gene was one of the first major successes of biotechnology. Before genetic engineering, diabetics relied on insulin extracted from pig and cow pancreases, which sometimes caused allergic reactions. Now, genetically engineered human insulin is identical to what your pancreas produces naturally.

Key Principles of Genetic Engineering

Genetic engineering operates on several fundamental principles that you must understand thoroughly:

1. Gene Isolation and Identification

Scientists must first identify and isolate the specific gene they want to work with. This involves understanding the gene’s sequence, its location in the genome, and how it’s regulated. Modern techniques like genome sequencing and bioinformatics make this process increasingly precise.

2. Vector-Mediated Gene Transfer

Genes don’t just jump from one organism to another naturally. They need a vehicle – a vector – to carry them. Vectors are typically modified viruses, plasmids, or other DNA molecules that can enter cells and integrate the foreign gene into the host’s genetic machinery.

3. Host Cell Transformation

The target organism (usually bacteria, yeast, or cultured cells) must be made competent to take up the foreign DNA. This often involves treating cells with chemicals or using physical methods to make their membranes permeable.

4. Selection and Screening

Not every cell will successfully take up and express the foreign gene. Scientists need methods to identify which cells have been successfully transformed. This usually involves antibiotic resistance genes or other selectable markers.

5. Gene Expression and Protein Production

Once the gene is in the host cell, it must be expressed at appropriate levels. This requires understanding gene regulation, promoter sequences, and the cellular environment needed for protein production.

2: The Molecular Toolkit – Enzymes and Vectors in Biotechnology

Restriction Enzymes: The Molecular Scissors

Restriction enzymes are the foundation tools of genetic engineering. These proteins, originally discovered in bacteria as a defense mechanism against viral DNA, can cut DNA at very specific sequences. Think of them as incredibly precise molecular scissors that recognize specific letter patterns in the DNA alphabet.

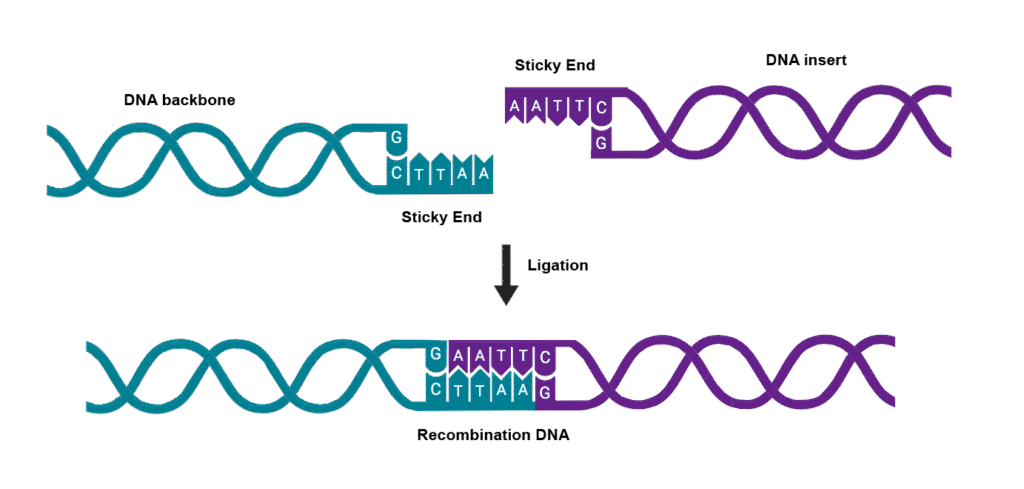

PROCESS: Restriction Enzyme Action: EcoRI recognizes the sequence GAATTC and cuts between G and A on both strands, creating complementary sticky ends that can pair with other DNA fragments cut by the same enzyme

Each restriction enzyme recognizes a specific sequence, typically 4-8 base pairs long. For example, EcoRI (named after E. coli strain RY13 where it was discovered) cuts DNA wherever it finds the sequence GAATTC. What’s remarkable is that it makes the same cut in this sequence whether it’s in human DNA, bacterial DNA, or plant DNA.

The cuts made by many restriction enzymes create “sticky ends” – short single-stranded overhangs that can base-pair with complementary sequences. This property is crucial for genetic engineering because it allows DNA fragments from different sources to be joined together precisely.

Common Error Alert: Students often confuse restriction enzymes with ligases. Remember: restriction enzymes CUT DNA, while ligases JOIN DNA fragments together.

Types of Restriction Enzymes and Their Applications

Type I Enzymes: These cut DNA at random sites far from their recognition sequences. They’re not useful for genetic engineering because the cuts aren’t predictable.

Type II Enzymes: These are the workhorses of biotechnology. They cut within or very close to their recognition sites, producing predictable fragments. Examples include EcoRI, BamHI, and HindIII.

Type III Enzymes: These cut at specific distances from their recognition sites but are less commonly used in genetic engineering.

For biotechnology applications, Type II enzymes are preferred because they produce consistent, predictable cuts that allow precise manipulation of DNA fragments.

DNA Ligases: The Molecular Glue

While restriction enzymes cut DNA, ligases join DNA fragments together. The most commonly used is T4 DNA ligase, derived from bacteriophage T4. This enzyme can join DNA fragments that have compatible sticky ends or even blunt ends (though less efficiently).

Understanding how ligases work is crucial for genetic engineering. The enzyme catalyzes the formation of phosphodiester bonds between the 3′-hydroxyl group of one DNA fragment and the 5′-phosphate group of another, effectively “sealing” the gaps in the sugar-phosphate backbone.

Vectors: The Molecular Vehicles

Vectors are DNA molecules that can replicate independently in host cells and carry foreign genes. Think of them as molecular vehicles that transport genes from one organism to another. The choice of vector depends on the specific application, the size of the gene to be cloned, and the type of host cell.

Plasmid Vectors

Plasmids are small, circular DNA molecules that exist independently of the main chromosome in bacterial cells. They’re ideal vectors because they:

- Replicate autonomously

- Are easily isolated and manipulated

- Can be transferred between bacterial cells

- Often carry antibiotic resistance genes for selection

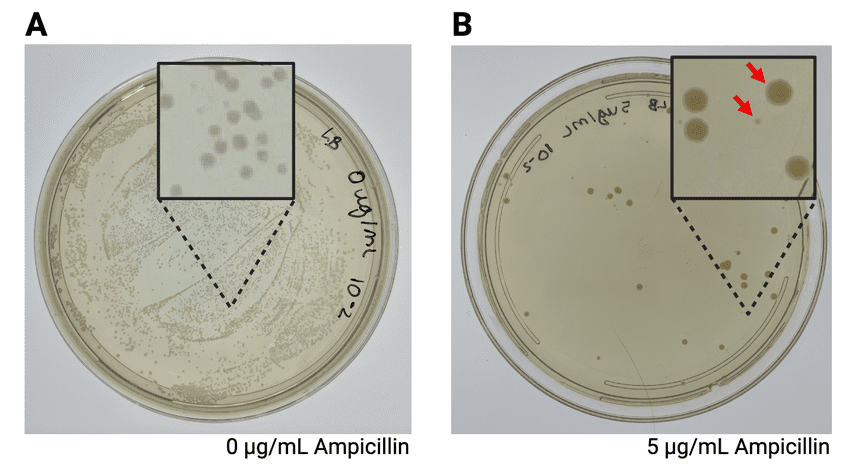

Real-World Biology: The pBR322 plasmid was one of the first engineered cloning vectors. It contains genes for resistance to ampicillin and tetracycline, allowing researchers to select for bacteria that have taken up the plasmid.

Characteristics of Ideal Vectors

An ideal cloning vector should have several key features:

1. Origin of Replication (ori): This sequence allows the vector to replicate independently in the host cell. Different origins work in different organisms, so the choice depends on your host system.

2. Selectable Markers: Usually antibiotic resistance genes that allow you to identify cells that have taken up the vector. If bacteria grow on antibiotic-containing medium, they must have the resistance gene from the vector.

3. Multiple Cloning Site (MCS): A region containing recognition sites for several different restriction enzymes, allowing flexible insertion of foreign DNA.

4. Small Size: Smaller vectors are easier to manipulate and more likely to be taken up by host cells.

5. High Copy Number: Vectors that replicate to high numbers per cell produce more of the cloned gene product.

Bacteriophage Vectors

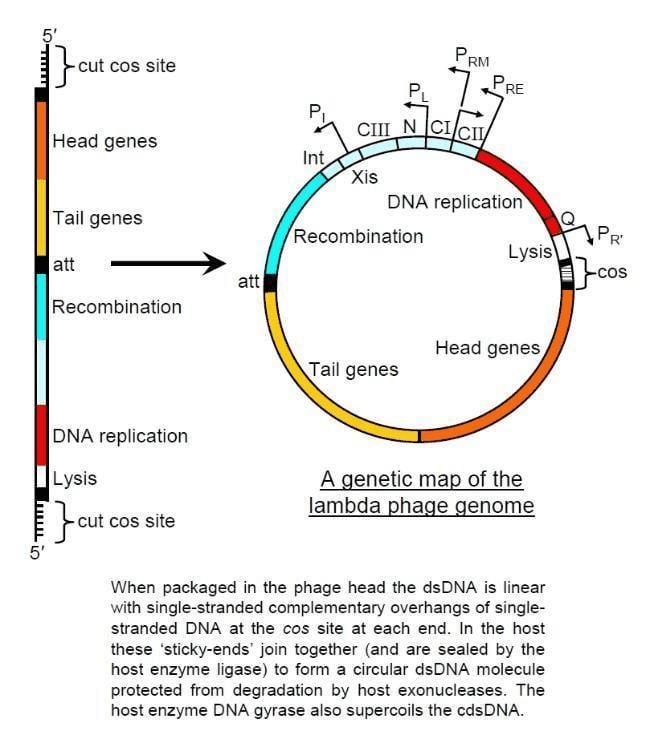

For cloning larger DNA fragments, bacteriophage (virus) vectors like lambda phage are used. These can accommodate larger inserts than plasmids and have efficient mechanisms for entering bacterial cells.

Lambda vectors can carry inserts up to about 23 kb, making them suitable for cloning larger genes or gene clusters. The phage life cycle ensures efficient delivery of the recombinant DNA into bacterial hosts.

3: The Process of Genetic Engineering – From Gene to Product

Step-by-Step Genetic Engineering Process

Understanding genetic engineering requires following the logical sequence of steps from identifying a useful gene to producing the final product. Let’s walk through this process using human insulin production as our example.

Step 1: Gene Identification and Isolation

The first challenge is identifying exactly which gene you want to clone. For insulin, scientists needed to isolate the gene encoding human insulin from the vast human genome. This involves:

- Locating the gene using genetic mapping techniques

- Understanding the gene’s structure, including exons, introns, and regulatory sequences

- Designing strategies to isolate the gene intact

Modern genome sequencing has made gene identification much easier, but it’s still a crucial first step that requires careful planning.

Step 2: Gene Cloning and Amplification

Once isolated, the gene must be amplified to produce enough material for further work. This typically involves:

- Inserting the gene into a cloning vector

- Transforming bacterial cells with the recombinant vector

- Selecting successfully transformed cells

- Growing large cultures to amplify the gene

PROCESS: Insulin Gene Cloning: The human insulin gene is inserted into a plasmid vector using compatible sticky ends created by restriction enzymes. The recombinant plasmid is then used to transform E. coli bacteria, which replicate the plasmid and express the insulin gene.

Step 3: Vector Construction

Creating a recombinant vector involves several precise molecular biology techniques:

- Cutting both the vector and the gene insert with the same restriction enzyme

- Mixing the cut vector and insert under conditions that favor base-pairing

- Using DNA ligase to seal the joins between vector and insert

- Transforming competent bacterial cells with the recombinant vector

Step 4: Transformation and Selection

Not every bacterial cell will take up the recombinant vector, so selection is necessary:

- Treat bacterial cells to make them competent (able to take up DNA)

- Mix competent cells with recombinant vectors

- Plate cells on selective medium (usually containing antibiotics)

- Only cells with the vector (and its resistance gene) will survive

Step 5: Screening for Recombinants

Even among antibiotic-resistant colonies, not all will contain the desired gene insert. Additional screening is needed:

- Colony PCR to check for the presence of the insert

- Restriction enzyme analysis of isolated plasmids

- DNA sequencing to confirm the correct sequence

Step 6: Expression and Production

Once you have confirmed recombinant clones, the focus shifts to protein production:

- Optimize culture conditions for maximum protein expression

- Scale up from laboratory cultures to industrial fermenters

- Purify the desired protein from bacterial lysates

- Test the protein for biological activity and safety

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Amplifying Specific DNA Sequences

PCR revolutionized molecular biology by allowing researchers to amplify specific DNA sequences millions of times in just a few hours. Think of it as a highly efficient molecular photocopying machine that can make billions of copies of a specific gene.

PROCESS: PCR Amplification: Three-step cycle repeated 25-35 times: 1) Denaturation at 94°C separates DNA strands, 2) Annealing at 50-65°C allows primers to bind to target sequences, 3) Extension at 72°C allows Taq polymerase to synthesize new DNA strands

Components Required for PCR:

- Template DNA: The DNA containing the sequence you want to amplify

- Primers: Short DNA sequences that define the boundaries of amplification

- Taq Polymerase: A heat-stable DNA polymerase that can work at high temperatures

- dNTPs: The four DNA building blocks (dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dTTP)

- Buffer and Mg²⁺: To provide optimal conditions for the enzyme

The PCR Cycle:

Each PCR cycle doubles the number of target sequences, leading to exponential amplification. After n cycles, you have 2ⁿ copies of the original sequence. This means that after 30 cycles, you have over a billion copies!

Applications of PCR in Biotechnology:

- Amplifying genes for cloning

- Genetic fingerprinting and forensics

- Medical diagnostics (detecting pathogens)

- Evolutionary studies using ancient DNA

- Quality control in biotechnology processes

Biology Check: Can you calculate how many copies of a DNA sequence you would have after 25 PCR cycles, starting with a single copy?

Challenges in Gene Expression

Getting a cloned gene to produce functional protein in a host organism involves overcoming several challenges:

Codon Usage Bias: Different organisms prefer different codons for the same amino acid. A human gene might use codons that are rare in E. coli, leading to poor expression.

Post-translational Modifications: Many proteins require modifications (like glycosylation) after translation. Bacterial systems may not be able to perform these modifications.

Protein Folding: Complex proteins may not fold correctly in bacterial cells, leading to inactive products or inclusion bodies (aggregated proteins).

Regulatory Sequences: The gene’s natural regulatory sequences may not function in the host organism, requiring the use of host-specific promoters.

4: Host Systems and Transformation Techniques

Choosing the Right Host Organism

The choice of host organism is crucial for successful genetic engineering. Each type of host has advantages and disadvantages that make it suitable for different applications.

Bacterial Hosts (E. coli)

Escherichia coli remains the most popular host for genetic engineering because:

- Fast growth (doubling time of about 20 minutes)

- Well-understood genetics and physiology

- Inexpensive to culture

- High levels of protein expression possible

- Extensive collection of modified strains available

However, bacterial hosts have limitations:

- Cannot perform complex post-translational modifications

- May not fold complex eukaryotic proteins correctly

- Lack membrane-bound organelles for certain proteins

- May produce endotoxins that complicate protein purification

Real-World Biology: Most recombinant human insulin is produced in E. coli bacteria. The bacteria are grown in large fermenters, and the insulin is harvested and purified from the bacterial cells.

Yeast Hosts (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)

Yeast offers advantages over bacterial systems:

- Eukaryotic cellular machinery for proper protein folding

- Ability to perform some post-translational modifications

- Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status for food applications

- Can secrete proteins into the growth medium

Yeast limitations include:

- Slower growth than bacteria

- More complex culture requirements

- Different glycosylation patterns than humans

Mammalian Cell Hosts

For proteins requiring complex modifications, mammalian cells are often necessary:

- Proper human-like post-translational modifications

- Correct protein folding and assembly

- Appropriate subcellular localization

Disadvantages include:

- Very slow growth and expensive culture media

- Risk of viral contamination

- Complex culture requirements

- Lower protein yields

Transformation Techniques

Getting foreign DNA into host cells requires overcoming the natural barriers that cells have against taking up external genetic material.

Transformation in Bacteria

Bacterial cells have cell walls and membranes that normally prevent DNA uptake. Several methods can make bacteria “competent” for transformation:

Chemical Competence: Treating cells with calcium chloride or other chemicals makes their membranes permeable to DNA. The mechanism isn’t fully understood, but it involves disrupting the normal membrane structure.

Electrocompetence: Brief electrical pulses create temporary pores in bacterial membranes, allowing DNA to enter. This method (electroporation) is often more efficient than chemical methods.

PROCESS: Bacterial Transformation: Competent cells are mixed with recombinant DNA on ice, heat-shocked at 42°C for 90 seconds, then returned to ice. The thermal shock is thought to drive DNA through membrane pores.

Transformation in Eukaryotic Cells

Eukaryotic cells present additional challenges because they have more complex membrane systems and often larger sizes.

Electroporation: High-voltage electrical pulses create temporary pores in the cell membrane, allowing DNA entry.

Microinjection: Direct injection of DNA into the cell nucleus using microscopic needles. This method is precise but labor-intensive.

Lipofection: DNA is complexed with cationic lipids that can fuse with cell membranes, delivering the DNA into the cytoplasm.

Viral Vectors: Modified viruses can efficiently deliver genes into eukaryotic cells by exploiting the virus’s natural infection mechanisms.

Selection and Screening Strategies

After transformation, only a small percentage of cells will have taken up the foreign DNA. Efficient selection and screening methods are essential for identifying successful transformants.

Antibiotic Selection

The most common selection method uses antibiotic resistance genes on the vector. Cells that haven’t taken up the vector will die when grown on antibiotic-containing medium, while transformed cells will survive and grow.

Blue-White Screening

This elegant system allows researchers to distinguish between vectors that have taken up an insert and those that haven’t. The method uses the lacZ gene (encoding β-galactosidase) with a multiple cloning site inserted within it.

- Vectors without inserts produce functional β-galactosidase, which cleaves X-gal to produce blue colonies

- Vectors with inserts disrupt the lacZ gene, resulting in white colonies

- White colonies are likely to contain the desired recombinant DNA

Reporter Genes

Genes encoding easily detectable proteins (like Green Fluorescent Protein) can be linked to the gene of interest, making it easy to identify expressing cells under appropriate conditions.

Optimizing Expression Systems

Getting high levels of protein production requires careful optimization of the expression system:

Promoter Choice: Strong, inducible promoters allow controlled, high-level expression. The lac promoter system in bacteria can be induced with IPTG when protein production is desired.

Culture Conditions: Temperature, pH, oxygen levels, and nutrient availability all affect protein expression. Cooler temperatures often improve protein folding, while higher temperatures may increase expression levels.

Codon Optimization: Modifying the gene sequence to use preferred codons for the host organism can dramatically improve expression levels.

Protein Fusion: Fusing the target protein to well-expressed proteins can improve production levels and facilitate purification.

5: Advanced Cloning Vectors and Specialized Applications

Plasmid Vectors: Beyond Basic Cloning

While simple plasmid vectors work well for basic cloning, specialized applications require more sophisticated vector systems.

Expression Vectors

These plasmids are designed specifically for high-level protein production:

- Strong promoters (like T7, tac, or trc) for high transcription levels

- Ribosome binding sites optimized for the host organism

- Inducible systems allowing controlled protein expression

- Fusion tags for protein purification and detection

Real-World Biology: The pET vector system uses bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase for extremely high levels of protein expression. The T7 polymerase is under control of an inducible promoter, allowing researchers to turn protein production on and off.

Shuttle Vectors

These versatile vectors can replicate in multiple host organisms, allowing easy transfer of cloned genes between different systems. For example, a yeast-bacterial shuttle vector can replicate in both E. coli (for easy manipulation) and yeast (for expression studies).

Binary Vectors

Used primarily for plant transformation, these vectors work in conjunction with Agrobacterium tumefaciens to transfer genes into plant cells. The system takes advantage of the bacterium’s natural ability to transfer DNA into plant cells.

Viral Vectors: Harnessing Nature’s Delivery Systems

Viruses have evolved sophisticated mechanisms for delivering genetic material into cells. Biotechnologists have modified these natural systems to create powerful gene delivery vectors.

Retroviral Vectors

Retroviruses integrate their genetic material into the host cell’s chromosome, making them useful for stable gene expression:

- Permanent integration ensures long-term expression

- Can infect a wide range of cell types

- Relatively large packaging capacity (8-10 kb)

- Safety concerns due to random integration

Adenoviral Vectors

These vectors don’t integrate into the host genome but can achieve high levels of transient expression:

- High efficiency of infection

- Can infect both dividing and non-dividing cells

- Large packaging capacity (up to 37 kb)

- Episomal replication reduces insertional mutagenesis risk

PROCESS: Adenoviral Gene Delivery: Modified adenovirus lacking essential genes for replication is used to deliver therapeutic genes. The virus can infect cells efficiently but cannot replicate, making it safer for gene therapy applications.

Lentiviral Vectors

A subclass of retroviruses that can infect non-dividing cells:

- Can infect neurons and other post-mitotic cells

- Lower immunogenicity than other viral vectors

- Stable integration with less tendency to silence

- Important for gene therapy applications

Artificial Chromosome Vectors

For cloning very large DNA fragments or entire genes with their regulatory sequences, artificial chromosome vectors are necessary.

Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs)

Based on bacterial F-factor plasmids, BACs can carry inserts of 150-300 kb:

- Stable maintenance of large inserts

- Low copy number reduces recombination problems

- Useful for genome sequencing projects

- Can clone entire gene clusters with regulatory elements

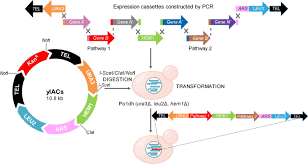

Yeast Artificial Chromosomes (YACs)

These can carry even larger inserts (200-2000 kb):

- Contain yeast centromere, telomeres, and origin of replication

- Can clone very large genomic regions

- Higher instability than BACs

- Useful for functional genomics studies

Specialized Cloning Strategies

Gateway Cloning

This system uses site-specific recombination to move genes between vectors:

- No restriction enzymes or ligases required

- High efficiency and directionality

- Easy to move genes between different expression systems

- Reduces cloning artifacts

TOPO Cloning

Uses topoisomerase enzymes for rapid, efficient cloning:

- Single-step cloning procedure

- No restriction enzyme digestion required

- High efficiency transformation

- Particularly useful for PCR products

Gibson Assembly

A method that uses overlapping DNA fragments and enzymes to assemble multiple fragments in a single reaction:

- Can assemble multiple fragments simultaneously

- No restriction enzyme sites required

- Useful for constructing complex plasmids

- Enables seamless cloning without scars

Vector Modifications for Specific Applications

Protein Purification Tags

Vectors can be modified to add peptide tags that facilitate protein purification:

- His-tags for metal affinity chromatography

- GST-tags for glutathione affinity purification

- FLAG-tags for immunoaffinity purification

- MBP-tags for improving protein solubility

Subcellular Localization Signals

For eukaryotic expression, vectors can include signals directing proteins to specific cellular compartments:

- Nuclear localization signals

- Mitochondrial targeting sequences

- Endoplasmic reticulum signal sequences

- Membrane anchoring domains

Biology Check: Why might you want to direct a recombinant protein to a specific subcellular compartment?

6: Biotechnology Applications in Medicine and Agriculture

Medical Applications: Revolutionizing Healthcare

Biotechnology has transformed modern medicine, providing new treatments for diseases that were previously incurable and improving the quality of life for millions of people worldwide.

Recombinant Pharmaceuticals

The production of human proteins in bacterial, yeast, or mammalian cells has created a new class of medicines:

Human Insulin: The first major success story of biotechnology. Recombinant human insulin is identical to pancreatic insulin but produced in E. coli or yeast. This eliminates allergic reactions sometimes caused by animal insulin and ensures a steady supply.

Growth Hormone: Recombinant human growth hormone treats children with growth hormone deficiency. Before biotechnology, growth hormone was extracted from human cadaver pituitaries, with limited supply and safety concerns.

Blood Clotting Factors: Factors VIII and IX for treating hemophilia are now produced recombinantly, eliminating the risk of viral transmission from blood products.

Real-World Biology: Factor VIII, used to treat hemophilia A, was previously isolated from donated blood plasma. The recombinant version eliminated the risk of HIV and hepatitis transmission that occurred in the 1980s before blood screening was available.

Monoclonal Antibodies

These laboratory-produced antibodies that target specific molecules have revolutionized both diagnosis and treatment:

- Cancer therapy (targeting tumor-specific antigens)

- Autoimmune disease treatment

- Organ transplant rejection prevention

- Diagnostic tests with high specificity

Gene Therapy

The direct introduction of genetic material into patient cells to treat disease:

- Correcting genetic defects (like in severe combined immunodeficiency)

- Cancer treatment using modified immune cells

- Vision restoration in inherited blindness

- Challenges include delivery methods and immune responses

Personalized Medicine

Biotechnology enables treatment tailored to individual genetic profiles:

- Pharmacogenomics (drug responses based on genetics)

- Targeted cancer therapies based on tumor genetics

- Genetic testing for disease predisposition

- Customized dosing based on genetic variants

Diagnostic Applications

Biotechnology has dramatically improved medical diagnostics, making tests faster, more accurate, and more accessible.

PCR-Based Diagnostics

The sensitivity of PCR allows detection of pathogens even when present in very small numbers:

- COVID-19 testing using RT-PCR

- HIV viral load monitoring

- Genetic disease diagnosis

- Cancer biomarker detection

PROCESS: RT-PCR for Virus Detection: RNA viruses are first converted to DNA using reverse transcriptase, then amplified using standard PCR. This allows detection of RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2 with high sensitivity and specificity.

DNA Microarrays and Sequencing

These technologies allow simultaneous analysis of thousands of genes:

- Cancer classification based on gene expression patterns

- Pharmacogenomic testing for drug responses

- Pathogen identification and antibiotic resistance testing

- Genetic variation analysis for disease risk assessment

Agricultural Biotechnology: Feeding the World

Agricultural biotechnology addresses the challenge of feeding a growing global population while dealing with climate change, pest resistance, and limited arable land.

Genetically Modified Crops

Genetic engineering has created crops with improved characteristics:

Pest Resistance: Bt corn and cotton contain genes from Bacillus thuringiensis that produce proteins toxic to specific insects. This reduces pesticide use and increases yields.

Herbicide Tolerance: Crops engineered to survive specific herbicides (like glyphosate) allow farmers to control weeds more effectively without damaging the crop.

Enhanced Nutrition: Golden rice contains genes for β-carotene production, potentially reducing vitamin A deficiency in developing countries.

Real-World Biology: Bt cotton has dramatically reduced pesticide use in many countries. In India, Bt cotton adoption led to a 50% reduction in pesticide applications while increasing yields by 30-40%.

Disease Resistance

Engineering crops to resist viral, bacterial, and fungal diseases:

- Papaya ringspot virus resistance in papaya

- Late blight resistance in potatoes

- Bacterial wilt resistance in bananas

- These modifications can save entire crops from devastating diseases

Environmental Stress Tolerance

Climate change makes stress tolerance increasingly important:

- Drought tolerance for water-limited regions

- Salt tolerance for coastal agriculture

- Temperature tolerance for changing climates

- Enhanced photosynthesis efficiency

Plant Transformation Techniques

Getting genes into plant cells requires specialized methods due to plant cell walls and tissue organization.

Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation

This bacterium naturally transfers DNA into plant cells and has been modified for genetic engineering:

- Uses the Ti plasmid system for DNA transfer

- Works well with dicotyledonous plants

- Can transfer large DNA fragments

- Natural process adapted for biotechnology

PROCESS: Agrobacterium Transformation: Plant tissue is wounded and infected with Agrobacterium carrying recombinant Ti plasmids. The bacterium transfers T-DNA containing the desired gene into plant cells, where it integrates into the nuclear genome.

Particle Bombardment (Gene Gun)

Physical method that shoots DNA-coated particles into plant cells:

- Works with monocots that are difficult to transform with Agrobacterium

- Can transform multiple genes simultaneously

- Useful for chloroplast transformation

- Less precise than Agrobacterium but more versatile

Protoplast Transformation

Plant cell walls are removed enzymatically, and DNA is introduced into the naked protoplasts:

- Allows direct DNA uptake

- Useful for basic research

- Plant regeneration can be challenging

- Less commonly used for crop development

Tissue Culture and Plant Regeneration

Successful plant genetic engineering requires the ability to regenerate whole plants from transformed cells:

Callus Culture: Undifferentiated plant cells grown on nutrient media

Shoot Regeneration: Hormonal treatments induce shoot formation from callus

Root Development: Different hormone combinations promote root formation

Acclimatization: Gradual adaptation of tissue culture plants to greenhouse conditions

INSERT DIAGRAM: Plant transformation workflow showing tissue culture, Agrobacterium infection, selection on antibiotic medium, shoot regeneration, and whole plant development

7: Industrial Biotechnology and Bioprocessing

Microbial Production Systems

Industrial biotechnology harnesses microorganisms to produce valuable compounds on a large scale. This field, sometimes called “white biotechnology,” uses biological systems to manufacture everything from pharmaceuticals to biofuels.

Fermentation Technology

Large-scale microbial cultivation requires sophisticated bioreactor systems:

- Batch Fermentation: Closed system where all nutrients are added at the beginning

- Fed-Batch Fermentation: Nutrients are added gradually during cultivation

- Continuous Fermentation: Steady-state system with continuous nutrient input and product removal

PROCESS: Industrial Insulin Production: E. coli containing human insulin genes are grown in 10,000-liter fermenters. The bacteria produce insulin as inclusion bodies, which are harvested, solubilized, refolded, and purified to pharmaceutical standards.

Optimization Strategies

Maximizing product yield requires careful control of multiple factors:

- pH Control: Maintains optimal conditions for enzyme activity

- Temperature Management: Balances growth rate with protein stability

- Oxygen Supply: Ensures adequate respiration for aerobic organisms

- Nutrient Feeding: Provides carbon and nitrogen sources without excess

- Foam Control: Prevents excessive foaming that can damage cells

Downstream Processing

Converting fermentation broth to pure product involves multiple steps:

- Cell Harvesting: Separating cells from culture medium

- Cell Lysis: Breaking cells to release intracellular products

- Primary Purification: Removing major contaminants

- Chromatographic Purification: Achieving pharmaceutical-grade purity

- Formulation: Preparing final product for storage and use

Enzyme Production and Applications

Enzymes are biological catalysts that can replace harsh chemical processes with environmentally friendly alternatives.

Industrial Enzyme Applications

- Detergents: Proteases, lipases, and amylases for stain removal

- Food Processing: Pectinases for juice clarification, lactase for lactose-free products

- Textiles: Cellulases for fabric softening, catalases for bleach removal

- Paper Industry: Xylanases for pulp bleaching, cellulases for fiber modification

- Biofuels: Cellulases and hemicellulases for biomass conversion

Real-World Biology: The enzyme α-amylase, produced by genetically modified bacteria, is used in high-fructose corn syrup production. This enzyme converts starch to glucose, which is then converted to fructose by glucose isomerase.

Enzyme Engineering

Modifying enzymes to improve their industrial properties:

- Thermostability: Engineering enzymes to work at higher temperatures

- pH Tolerance: Adapting enzymes for extreme pH conditions

- Substrate Specificity: Modifying enzymes to work on different substrates

- Activity Enhancement: Increasing catalytic efficiency through protein design

Biofuel Production

Biotechnology offers sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels through biological conversion of biomass.

Ethanol Production

Fermentation of sugars and starches to produce ethanol fuel:

- First Generation: Using corn starch or sugarcane

- Second Generation: Converting cellulosic biomass (wood, agricultural waste)

- Genetic Engineering: Improving yeast strains for higher alcohol tolerance

- Process Integration: Combining enzyme production and fermentation

PROCESS: Cellulosic Ethanol Production: Lignocellulosic biomass is pretreated to break down cell walls, then treated with cellulase enzymes to convert cellulose to glucose, which is fermented to ethanol by modified yeast strains.

Biodiesel Production

Using microorganisms to produce diesel fuel alternatives:

- Algae Cultivation: High-lipid microalgae as feedstock

- Genetic Modification: Engineering algae for higher oil content

- Extraction Methods: Efficient oil recovery from algal biomass

- Process Economics: Reducing costs to compete with petroleum diesel

Advanced Biofuels

Next-generation fuels produced through synthetic biology:

- Synthetic Biology Approaches: Engineering microorganisms to produce hydrocarbons

- Metabolic Engineering: Redirecting cellular metabolism toward fuel production

- Drop-in Fuels: Biofuels identical to petroleum products

- Scale-up Challenges: Moving from laboratory to industrial production

Biosynthesis of High-Value Compounds

Biotechnology enables production of complex molecules that are difficult or expensive to synthesize chemically.

Pharmaceutical Intermediates

Microbial production of drug precursors:

- Statins: Cholesterol-lowering drugs produced by fungi

- Antibiotics: Penicillin, streptomycin, and other antimicrobials

- Vitamins: B12, riboflavin, and other essential nutrients

- Hormones: Insulin, growth hormone, and reproductive hormones

Fine Chemicals

High-value, low-volume chemicals for specialized applications:

- Amino Acids: Building blocks for pharmaceuticals and food additives

- Organic Acids: Citric acid, lactic acid for food and chemical industries

- Specialty Polymers: Biodegradable plastics and biomaterials

- Flavors and Fragrances: Natural compounds for food and cosmetic industries

Biology Check: Why might a pharmaceutical company choose microbial production over chemical synthesis for a complex drug molecule?

8: Ethics, Safety, and Future Directions in Biotechnology

Biosafety Considerations

As biotechnology becomes more powerful, ensuring the safety of both laboratory workers and the general public becomes increasingly important.

Laboratory Biosafety Levels

Different levels of containment are required depending on the risk posed by the organisms being used:

BSL-1: Basic protection for organisms posing minimal risk to healthy adults (like most E. coli strains used in cloning)

BSL-2: Moderate protection for organisms with moderate risk potential (like some pathogenic bacteria)

BSL-3: High protection for organisms that may cause serious disease (like Mycobacterium tuberculosis)

BSL-4: Maximum protection for extremely dangerous organisms (like Ebola virus)

Real-World Biology: Most undergraduate biotechnology teaching labs operate at BSL-1 level, using non-pathogenic strains of E. coli that have been modified to survive only under laboratory conditions.

Risk Assessment Framework

Evaluating biotechnology applications requires systematic risk assessment:

- Hazard Identification: What are the potential harmful effects?

- Exposure Assessment: How might people or the environment be exposed?

- Risk Characterization: What is the likelihood and magnitude of harm?

- Risk Management: What measures can reduce or eliminate risks?

Environmental Release Protocols

Before genetically modified organisms can be released into the environment, extensive testing is required:

- Contained Greenhouse Studies: Initial testing under controlled conditions

- Small-Scale Field Trials: Limited environmental testing with monitoring

- Large-Scale Trials: Extensive field testing across multiple locations

- Regulatory Approval: Government review of safety data before commercial release

Ethical Considerations in Biotechnology

The power to modify life raises profound ethical questions that society must address.

Informed Consent

Patients and research participants must understand the risks and benefits:

- Gene Therapy Trials: Explaining experimental nature and potential risks

- Genetic Testing: Understanding implications of test results

- Research Participation: Clear explanation of study procedures and risks

- Privacy Concerns: Protecting genetic information from discrimination

Genetic Privacy and Discrimination

Genetic information could be misused if not properly protected:

- Insurance Discrimination: Using genetic information to deny coverage

- Employment Discrimination: Genetic screening for job applications

- Data Security: Protecting genetic databases from unauthorized access

- Family Implications: Genetic information affects relatives, not just individuals

Real-World Biology: The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) in the United States prohibits genetic discrimination in health insurance and employment, addressing some concerns about genetic testing.

Agricultural Ethics

Genetically modified crops raise questions about food safety, environmental impact, and social justice:

- Food Safety: Long-term effects of consuming GM foods

- Environmental Impact: Effects on non-target organisms and ecosystems

- Farmer Rights: Patent issues and seed saving restrictions

- Global Justice: Access to improved crops in developing countries

Enhancement vs. Treatment

Distinguishing between treating disease and enhancing normal human capabilities:

- Therapeutic Applications: Using biotechnology to treat genetic diseases

- Enhancement Applications: Improving normal human traits

- Designer Babies: Genetic modification of embryos for desired traits

- Social Implications: Creating genetic “haves” and “have-nots”

Regulatory Frameworks

Biotechnology is regulated by multiple agencies with overlapping jurisdictions.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

Regulates biotechnology products used as foods, drugs, or medical devices:

- Drug Approval Process: Clinical trials and safety testing for biotech drugs

- Food Safety Assessment: Evaluation of genetically modified foods

- Medical Device Regulation: Oversight of diagnostic biotechnology products

- Manufacturing Standards: Good Manufacturing Practices for biotech products

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Regulates biotechnology products with environmental applications:

- Pesticide Regulation: Bt crops and other biopesticides

- Environmental Release: Permits for field testing of GM organisms

- Risk Assessment: Environmental impact evaluation of biotech products

- Monitoring Requirements: Post-market surveillance of environmental releases

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)

Regulates agricultural biotechnology applications:

- Plant Health: Preventing introduction of plant pests

- Field Testing: Permits for experimental crops

- Interstate Commerce: Regulating movement of GM crops

- International Trade: Coordinating with other countries on GM crop approvals

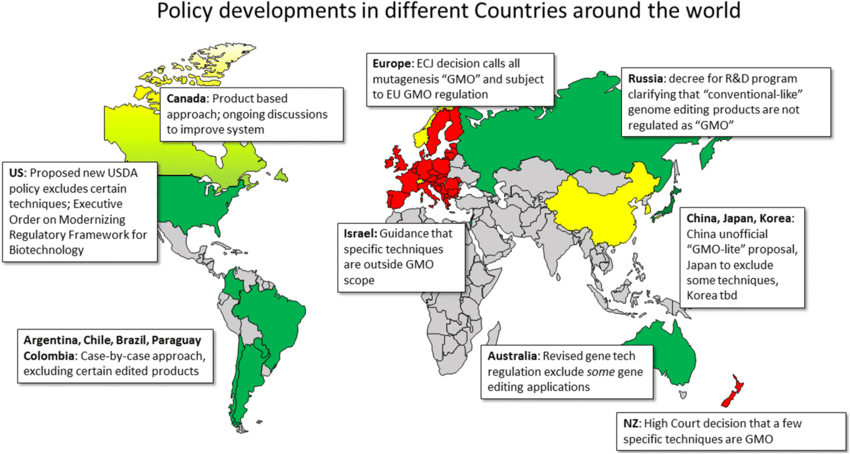

International Perspectives and Harmonization

Different countries have adopted varying approaches to biotechnology regulation, creating challenges for global commerce and development.

European Union Approach

Generally more restrictive than the United States:

- Precautionary Principle: Requiring proof of safety before approval

- Labeling Requirements: Mandatory labeling of GM foods

- Coexistence Policies: Keeping GM and non-GM crops separate

- Public Participation: Extensive public consultation in regulatory decisions

Developing Country Challenges

Many developing countries lack regulatory infrastructure:

- Capacity Building: Training regulators and scientists

- Technology Transfer: Accessing biotechnology developments

- International Cooperation: Harmonizing regulations across borders

- Resource Constraints: Limited funds for regulatory oversight

Future Directions and Emerging Technologies

Biotechnology continues to evolve rapidly, with new techniques and applications constantly emerging.

CRISPR-Cas9 and Gene Editing

Revolutionary gene editing technology with broad applications:

- Precision Medicine: Correcting genetic defects in patients

- Agricultural Applications: Improving crop traits without traditional genetic modification

- Basic Research: Understanding gene function through targeted modifications

- Ethical Considerations: Editing human embryos and germline modifications

Synthetic Biology

Engineering biological systems with predictable behaviors:

- Biological Circuits: Programming cells like electronic devices

- Metabolic Engineering: Designing cellular pathways for desired products

- Artificial Life: Creating organisms with entirely synthetic genomes

- Biocontainment: Engineering organisms that cannot survive outside laboratories

Real-World Biology: Scientists have created synthetic bacteria with entirely artificial genomes, demonstrating that life can be programmed like a computer. These organisms could be designed to produce medicines, clean up pollution, or perform other useful functions.

Personalized Medicine

Tailoring treatments to individual genetic profiles:

- Pharmacogenomics: Customizing drug selection and dosing

- Cancer Genomics: Targeting therapies to specific tumor genetics

- Rare Disease Treatment: Developing therapies for small patient populations

- Preventive Medicine: Using genetic information to prevent disease

Regenerative Medicine

Using biotechnology to repair or replace damaged tissues:

- Stem Cell Therapy: Using pluripotent cells to generate new tissues

- Tissue Engineering: Growing organs and tissues in the laboratory

- Gene Therapy: Correcting genetic defects in specific tissues

- 3D Bioprinting: Using biotechnology and engineering to create tissues

Environmental Applications

Using biotechnology to address environmental challenges:

- Bioremediation: Using microorganisms to clean up pollution

- Carbon Capture: Engineering organisms to remove CO2 from the atmosphere

- Sustainable Manufacturing: Replacing chemical processes with biological ones

- Conservation Biology: Using genetic techniques to preserve endangered species

Practice Problems Section

Multiple Choice Questions

Question 1: Which of the following enzymes is essential for joining DNA fragments in genetic engineering?

a) Restriction endonuclease

b) DNA ligase

c) DNA polymerase

d) Reverse transcriptase

Detailed Solution: The correct answer is (b) DNA ligase. While restriction endonucleases cut DNA at specific sequences and DNA polymerase synthesizes new DNA strands, DNA ligase is specifically responsible for joining DNA fragments by forming phosphodiester bonds between adjacent nucleotides. In genetic engineering, after restriction enzymes cut both the vector and insert DNA, ligase is used to seal the gaps and create a continuous DNA molecule. T4 DNA ligase is commonly used because it can join both sticky and blunt ends, though it works more efficiently with compatible sticky ends.

Question 2: The most commonly used bacterial host for genetic engineering is:

a) Bacillus subtilis

b) Pseudomonas aeruginosa

c) Escherichia coli

d) Staphylococcus aureus

Detailed Solution: The correct answer is (c) Escherichia coli. E. coli is preferred because: 1) It has well-characterized genetics and physiology, 2) It grows rapidly with a doubling time of about 20 minutes, 3) It’s easy and inexpensive to culture, 4) Many modified strains are available for specific applications, 5) It can achieve high levels of recombinant protein expression, and 6) Extensive molecular tools and vectors have been developed for E. coli systems. While other bacteria can be used as hosts, none match E. coli’s combination of convenience, efficiency, and available tools.

Question 3: Which vector would be most appropriate for cloning a 200 kb genomic DNA fragment?

a) Plasmid vector

b) Bacteriophage lambda vector

c) Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC)

d) M13 vector

Detailed Solution: The correct answer is (c) Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC). Different vectors have different insert capacity limits: plasmids can typically carry 5-10 kb, bacteriophage lambda vectors can accommodate up to 23 kb, and M13 vectors are suitable for smaller fragments. BACs, based on the E. coli F-factor, can carry inserts of 150-300 kb, making them ideal for large genomic clones. The low copy number of BACs also reduces problems with recombination and rearrangement that can occur with large inserts in high-copy vectors.

Question 4: In PCR, the primer annealing step typically occurs at:

a) 94°C

b) 72°C

c) 50-65°C

d) 37°C

Detailed Solution: The correct answer is (c) 50-65°C. PCR consists of three temperature steps: denaturation at 94°C to separate DNA strands, annealing at 50-65°C to allow primers to bind to their complementary sequences, and extension at 72°C for Taq polymerase activity. The exact annealing temperature depends on the length and GC content of the primers – longer primers and those with high GC content require higher annealing temperatures. The annealing temperature is typically set 2-5°C below the calculated melting temperature (Tm) of the primers.

Question 5: Which selection method allows discrimination between recombinant and non-recombinant clones?

a) Antibiotic resistance selection only

b) Blue-white screening using lacZ gene

c) Growth on minimal medium

d) Temperature-sensitive selection

Detailed Solution: The correct answer is (b) Blue-white screening using lacZ gene. This method uses the lacZ gene encoding β-galactosidase with a multiple cloning site inserted within it. When the substrate X-gal is present: non-recombinant vectors produce functional β-galactosidase, cleaving X-gal to produce blue colonies, while recombinant vectors (with inserts) disrupt the lacZ gene, resulting in white colonies. This allows easy visual discrimination between vectors that contain inserts (white) and those that don’t (blue). Antibiotic resistance alone only selects for transformed cells but doesn’t distinguish recombinants.

Case Study Analysis Problems

Case Study 1: Human Growth Hormone Production

A biotechnology company wants to produce human growth hormone (hGH) in E. coli for treating growth hormone deficiency in children. The company has isolated the hGH gene and needs to design a production system.

Part A: What modifications might be needed to express human growth hormone effectively in E. coli? Consider codon usage, protein folding, and regulatory sequences.

Detailed Solution: Several modifications would be necessary for effective hGH expression in E. coli:

1) Codon Optimization: The human hGH gene should be modified to use codons preferred by E. coli, as humans and bacteria have different codon usage patterns. Rare codons in E. coli can limit translation efficiency.

2) Promoter Replacement: The natural human promoter won’t function in E. coli. A strong bacterial promoter like T7, tac, or trc should be used, preferably with inducible control to prevent toxic effects during cell growth.

3) Ribosome Binding Site: A bacterial ribosome binding site (Shine-Dalgarno sequence) must be included upstream of the start codon for efficient translation initiation.

4) Protein Folding Considerations: hGH requires disulfide bonds for activity. E. coli’s reducing cytoplasm may not allow proper folding, so expression in the periplasm or use of folding helper proteins might be necessary.

5) N-terminal Methionine: Bacterial expression will add an N-terminal methionine that may need to be removed by methionine aminopeptidase or by using a cleavable signal sequence.

Part B: How would you verify that the produced protein is authentic human growth hormone with biological activity?

Detailed Solution: Authentication would involve multiple analytical approaches:

1) Protein Characterization:

- SDS-PAGE to confirm molecular weight (22 kDa for hGH)

- Western blot using anti-hGH antibodies for specific identification

- N-terminal amino acid sequencing to confirm proper sequence

- Mass spectrometry for precise molecular weight determination

2) Structural Analysis:

- Circular dichroism spectroscopy to verify proper secondary structure

- Differential scanning calorimetry to assess thermal stability

- Size exclusion chromatography to confirm monomeric state

3) Biological Activity Testing:

- Cell-based assays using growth hormone-responsive cell lines

- Receptor binding assays to confirm interaction with hGH receptors

- In vivo bioassays using appropriate animal models

- Comparison with reference standards from established sources

4) Purity Assessment:

- HPLC analysis for purity and related substances

- Endotoxin testing (crucial for bacterial-produced proteins)

- Host cell protein contamination analysis

- DNA contamination testing

Case Study 2: Developing Drought-Resistant Crops

Agricultural scientists want to develop drought-resistant wheat by introducing genes from a desert plant that produces protective proteins during water stress.

Part A: Design a strategy for identifying and cloning drought-resistance genes from the desert plant.

Detailed Solution: A systematic approach would involve:

1) Gene Discovery:

- Subject desert plants to controlled drought stress and analyze gene expression changes using RNA sequencing

- Compare gene expression between stressed and non-stressed plants to identify upregulated genes

- Use bioinformatics to identify genes encoding proteins with known roles in drought tolerance (e.g., late embryogenesis abundant proteins, osmoprotectants)

2) Gene Validation:

- Clone identified genes into bacterial expression vectors to produce recombinant proteins

- Test protein function in vitro (e.g., protective effects against dehydration)

- Express genes in model plants (Arabidopsis) to confirm drought tolerance function

3) Gene Cloning Strategy:

- Extract total RNA from drought-stressed desert plants

- Use reverse transcriptase to synthesize cDNA (to avoid introns that wheat might not process correctly)

- Amplify genes of interest using PCR with gene-specific primers

- Clone into plant transformation vectors with appropriate promoters

4) Vector Construction:

- Use strong, stress-inducible promoters (like those activated by abscisic acid)

- Include selectable markers for plant transformation (antibiotic or herbicide resistance)

- Add transcriptional terminators for proper mRNA processing

Part B: What experimental approach would you use to test drought tolerance in the transformed wheat plants?

Detailed Solution: A comprehensive testing strategy would include:

1) Controlled Environment Testing:

- Grow transformed and control plants under identical conditions

- Subject plants to graduated water stress (progressive drought)

- Monitor physiological parameters: leaf water content, stomatal conductance, photosynthesis rate

- Measure survival rates and recovery after rewatering

2) Molecular Analysis:

- Confirm transgene expression using RT-PCR or qPCR

- Analyze accumulation of drought-protective proteins

- Measure osmolyte concentrations (proline, glycine betaine)

- Monitor stress-responsive gene expression

3) Field Testing:

- Conduct multi-location field trials across different environments

- Test under natural drought conditions and supplemental irrigation treatments

- Measure agronomic performance: yield, grain quality, biomass production

- Assess environmental adaptation and stability

4) Comparative Analysis:

- Compare with non-transformed controls and commercial drought-tolerant varieties

- Statistical analysis of multiple parameters across replicated experiments

- Economic analysis of yield benefits under drought conditions

Experimental Design Questions

Question 1: You want to determine whether a newly cloned gene enhances antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Design a controlled experiment to test this hypothesis.

Detailed Solution:

Experimental Design:

Hypothesis: The cloned gene increases bacterial resistance to a specific antibiotic.

Variables:

- Independent variable: Presence/absence of the cloned gene

- Dependent variable: Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antibiotic

- Controls: Bacteria with empty vector, untransformed bacteria

Materials Needed:

- Bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli)

- Cloned gene in expression vector

- Empty vector (negative control)

- Target antibiotic

- Culture media and plates

- Serial dilution equipment

Experimental Procedure:

1) Strain Preparation:

- Transform bacteria with: a) recombinant vector containing gene, b) empty vector (negative control), c) leave some bacteria untransformed

- Confirm transformation by plating on selective medium

2) MIC Determination:

- Prepare serial dilutions of antibiotic (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 μg/ml)

- Inoculate each concentration with equal numbers of each bacterial strain

- Incubate under standard conditions (37°C, appropriate time)

- Determine lowest concentration preventing visible growth (MIC)

3) Data Collection:

- Record MIC values for each strain

- Perform at least three independent replicates

- Use multiple bacterial colonies from each transformation

4) Controls:

- Positive control: Known antibiotic-resistant strain

- Negative control: Untransformed bacteria and empty vector

- Media control: Ensure sterility and proper antibiotic activity

Expected Results: If the hypothesis is correct, bacteria with the cloned gene should show higher MIC values than controls.

Question 2: Design an experiment to optimize protein expression levels in a bacterial system.

Detailed Solution:

Experimental Objective: Maximize recombinant protein production while maintaining protein solubility and biological activity.

Variables to Optimize:

1) Promoter Systems: Test different promoters (T7, tac, trc, ara)

2) Induction Conditions: IPTG concentration (0-1 mM), induction timing

3) Culture Conditions: Temperature (25-37°C), pH (6.5-8.0)

4) Expression Duration: Time after induction (2-24 hours)

5) Cell Density: OD600 at induction (0.4-0.8)

Experimental Design:

Phase 1: Screening Phase

- Test each variable independently using one-factor-at-a-time approach

- Use small-scale cultures (5-10 ml) for rapid screening

- Measure total protein expression and soluble fraction

- Use SDS-PAGE and densitometry for quantification

Phase 2: Optimization Phase

- Use factorial design or response surface methodology

- Combine optimal levels from Phase 1 screening

- Scale up to larger volumes (50-100 ml) for detailed analysis

- Include protein activity assays if applicable

Measurements:

1) Expression Levels:

- Total recombinant protein (SDS-PAGE analysis)

- Soluble vs. insoluble protein fractions

- Protein concentration (Bradford or BCA assay)

2) Cell Health:

- Growth rate and final cell density

- Cell viability (plating efficiency)

- Culture morphology and color

3) Protein Quality:

- Protein solubility and aggregation

- Biological activity (if assay available)

- Proteolytic degradation assessment

Controls:

- Uninduced cultures (baseline expression)

- Empty vector controls (background protein levels)

- Positive controls (known high-expressing system)

Data Analysis:

- Statistical analysis of expression levels across conditions

- Cost-benefit analysis considering yield vs. culture complexity

- Scalability assessment for industrial production

Common Exam Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Mistake 1: Confusing Enzymes and Their Functions

Students often mix up restriction enzymes, ligases, and polymerases.

Prevention Strategy: Create a table summarizing each enzyme’s function, source, and specific role in genetic engineering. Remember the simple rule: restriction enzymes CUT, ligases JOIN, polymerases SYNTHESIZE.

Mistake 2: Incomplete Process Descriptions

Many students provide partial explanations of complex processes like PCR or gene cloning.

Prevention Strategy: Memorize complete step-by-step procedures. For PCR, always include all three temperature steps with their purposes. For gene cloning, include isolation, insertion, transformation, selection, and expression.

Mistake 3: Vague Examples and Applications

Using generic examples instead of specific, well-explained applications.

Prevention Strategy: Learn detailed examples for each application area. For medical applications, know specific examples like human insulin, growth hormone, and factor VIII, including why biotechnology was needed and how it improved treatment.

Common Error Alert: Don’t just say “bacteria produce human proteins.” Specify which bacteria (E. coli), which proteins (insulin, growth hormone), and why this is advantageous (identical to human proteins, no allergic reactions, unlimited supply).

Mistake 4: Ignoring Safety and Ethical Considerations

Students often focus only on technical aspects and ignore important societal implications.

Prevention Strategy: For every major application, consider both benefits and potential risks. Be prepared to discuss regulatory requirements, environmental concerns, and ethical issues.

Conclusion and Next Steps

As you complete your study of biotechnology, you’ve gained insight into one of the most dynamic and impactful fields in modern science. The principles and techniques you’ve learned – from restriction enzymes and PCR to gene cloning and protein expression – form the foundation of a revolution that’s transforming medicine, agriculture, and industry.

Connecting Biotechnology to Your Future

Whether you’re planning to pursue higher education in biology, considering a career in biotechnology, or simply want to be an informed citizen in our increasingly science-driven world, the knowledge you’ve gained will serve you well. The biotechnology industry offers diverse career opportunities, from research and development to regulatory affairs, quality control, and business development.

Research and Development: Scientists develop new biotechnology products and improve existing processes. This includes molecular biologists, geneticists, protein chemists, and bioprocess engineers.

Quality Control and Regulatory Affairs: Professionals ensure products meet safety and efficacy standards. They work with government agencies to obtain approvals for new products and maintain compliance with regulations.

Manufacturing and Production: Specialists optimize large-scale production of biotechnology products, from fermentation to purification and formulation.

Business and Commercialization: Professionals help bring biotechnology discoveries from the laboratory to the marketplace, including market analysis, business development, and strategic planning.

The Evolving Landscape of Biotechnology

The field continues to evolve rapidly with new technologies and applications emerging constantly. Gene editing technologies like CRISPR-Cas9 are revolutionizing both research and therapy. Synthetic biology is enabling the engineering of biological systems with predictable behaviors. Personalized medicine is moving from concept to clinical reality.

Emerging Technologies to Watch:

- Base Editing and Prime Editing: More precise gene editing technologies

- Epigenome Editing: Modifying gene expression without changing DNA sequence

- Organoids and Tissue Engineering: Growing human tissues and organs in the laboratory

- Artificial Intelligence in Drug Discovery: Using machine learning to design new medicines

- Sustainable Biotechnology: Using biological systems to address environmental challenges

Preparing for Advanced Study

If you’re planning to study biotechnology, biochemistry, or related fields in college, you’ll build on the foundation you’ve established. Advanced courses will delve deeper into:

- Molecular Biology Techniques: More sophisticated methods for studying and manipulating genes

- Protein Structure and Function: Understanding how protein structure relates to biological activity

- Metabolic Engineering: Designing cellular pathways for specific purposes

- Bioinformatics: Using computational tools to analyze biological data

- Bioprocess Engineering: Scaling up laboratory processes for industrial production

Final Thoughts on Exam Success

As you prepare for your CBSE examination, remember that biotechnology is not just a collection of facts to memorize – it’s a logical, interconnected field where each concept builds on previous knowledge. Understanding the underlying principles will help you tackle any question format, whether it asks for basic definitions, detailed processes, or complex applications.

Your study of biotechnology represents more than preparation for an examination – it’s your introduction to understanding how science can address humanity’s greatest challenges. From producing life-saving medicines to feeding a growing global population, from cleaning up environmental pollution to developing sustainable energy sources, biotechnology offers tools for building a better future.

The knowledge and analytical skills you’ve developed will serve you well, whether you become a biotechnology professional, a informed healthcare consumer, or simply a scientifically literate citizen. As you move forward in your education and career, remember that science is not just about understanding the natural world – it’s about using that understanding to improve life for everyone.

The future of biotechnology is bright, filled with exciting possibilities and important challenges. Your generation will play a crucial role in determining how these powerful technologies are developed and applied. By mastering the fundamentals you’ve studied and staying curious about new developments, you’ll be prepared to contribute to this exciting field and help shape its positive impact on society.

Real-World Biology: Many of today’s leading biotechnology researchers and entrepreneurs started their journey with strong performance in high school biology courses. Your success in understanding these concepts could be the first step toward a career that changes the world.

As you complete your preparation for the CBSE Class 12 Biology examination, you can be confident that you’ve gained a solid understanding of one of science’s most important and rapidly advancing fields. The principles, processes, and applications you’ve mastered will serve as valuable knowledge throughout your academic and professional career, regardless of the path you choose to follow.

Good luck with your examination, and remember that learning doesn’t end with the test – it’s just the beginning of a lifelong journey of discovery and understanding in the fascinating world of biotechnology.

Recommended –