Introduction: The Physics of Everyday Collisions

Every day, you witness countless examples of linear momentum in action. When you catch a baseball, your hands automatically move backward to reduce the impact force. When you’re in a car that suddenly brakes, your body continues forward due to its momentum. These everyday experiences demonstrate one of physics’ most fundamental and powerful conservation laws.

Linear momentum governs everything from subatomic particle interactions in particle accelerators to the orbital mechanics of planets. Understanding momentum isn’t just about passing the AP Physics C exam – it’s about comprehending how motion and forces interact in our universe. This conservation principle helped NASA navigate spacecraft to distant planets and enables engineers to design safer vehicles through crumple zone technology.

In this comprehensive guide, you’ll master the concepts that frequently appear on the AP Physics C: Mechanics exam. We’ll explore not just the mathematical formulations, but the physical intuition that makes momentum problems second nature. By the end of this study guide, you’ll approach momentum problems with confidence and tackle even the most challenging collision scenarios with systematic precision.

Learning Objectives: What You’ll Master

By completing this unit, you will demonstrate mastery of these College Board AP Physics C: Mechanics standards:

- Objective 4.1: Calculate linear momentum as the product of mass and velocity, understanding its vector nature and significance in physical systems

- Objective 4.2: Apply the impulse-momentum theorem to analyze how forces change an object’s momentum over time

- Objective 4.3: Implement conservation of momentum to solve collision and explosion problems in isolated systems

- Objective 4.4: Distinguish between elastic and inelastic collisions using both momentum and energy conservation principles

- Objective 4.5: Analyze center of mass motion and its relationship to external forces acting on multi-object systems

- Objective 4.6: Design and analyze experiments involving momentum conservation, including proper data collection and error analysis techniques

These objectives form the foundation for understanding more advanced physics concepts you’ll encounter in university-level mechanics and modern physics courses.

1: Fundamental Concepts – Understanding Momentum’s Physical Meaning

What Is Linear Momentum?

Linear momentum represents the “quantity of motion” an object possesses. Unlike velocity, which only considers how fast something moves, momentum accounts for both speed and mass. A massive freight train moving slowly can have the same momentum as a small car moving rapidly.

[EQUATION: Linear Momentum: p⃗ = mv⃗, where p⃗ is momentum vector (kg⋅m/s), m is mass (kg), and v⃗ is velocity vector (m/s)]

The vector nature of momentum means direction matters crucially. Two identical cars traveling at the same speed in opposite directions have momenta that cancel when added together. This vector property becomes essential when analyzing multi-dimensional collision problems.

Physics Check: Momentum Intuition

Consider these scenarios and predict which has greater momentum:

- A 2000 kg car traveling at 15 m/s eastward

- A 1000 kg motorcycle traveling at 30 m/s eastward

- A 4000 kg truck at rest

Answer: The motorcycle has the greatest momentum (30,000 kg⋅m/s), followed by the car (30,000 kg⋅m/s) – they’re equal! The stationary truck has zero momentum despite its large mass.

Momentum vs. Inertia: A Critical Distinction

Students often confuse momentum with inertia, but they’re fundamentally different concepts. Inertia describes an object’s resistance to changes in motion and depends only on mass. Momentum quantifies the actual motion and depends on both mass and velocity. A stationary elephant has enormous inertia but zero momentum, while a flying mosquito has minimal inertia but measurable momentum.

Real-World Physics: Momentum in Transportation Safety

Modern vehicle safety relies heavily on momentum principles. Crumple zones increase collision duration, reducing peak forces on passengers according to the impulse-momentum theorem. Similarly, airbags extend the time over which your momentum changes during impact, dramatically reducing the forces your body experiences. Understanding momentum helps engineers design protection systems that save thousands of lives annually.

2: Mathematical Framework – The Impulse-Momentum Theorem

Deriving the Impulse-Momentum Theorem

Starting with Newton’s Second Law in its most general form:

[EQUATION: F⃗ = dp⃗/dt, where F⃗ is net force (N), p⃗ is momentum (kg⋅m/s), and t is time (s)]

Rearranging and integrating over time interval Δt:

[EQUATION: ∫F⃗dt = Δp⃗, where ∫F⃗dt is impulse J⃗ (N⋅s) and Δp⃗ is change in momentum (kg⋅m/s)]

This gives us the impulse-momentum theorem:

[EQUATION: J⃗ = Δp⃗ = m(v⃗f – v⃗i), where J⃗ is impulse, v⃗f is final velocity, and v⃗i is initial velocity]

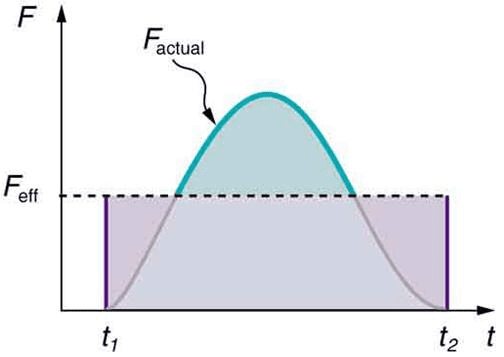

Understanding Impulse Graphically

When force varies with time, impulse equals the area under the force-time graph. This graphical interpretation proves invaluable for analyzing complex force profiles, such as those occurring during collisions or when objects interact with springs.

Variable Force Applications

For forces that change with time, we must integrate:

[EQUATION: J⃗ = ∫(t1 to t2) F⃗(t)dt, where F⃗(t) represents time-varying force]

This integration becomes particularly important when analyzing electromagnetic forces, spring interactions, or aerodynamic drag effects.

Common Error Alert: Sign Conventions

Always establish consistent coordinate systems before solving momentum problems. Many students lose points by inconsistently applying positive and negative directions. Choose your positive direction at the beginning and stick with it throughout the entire problem.

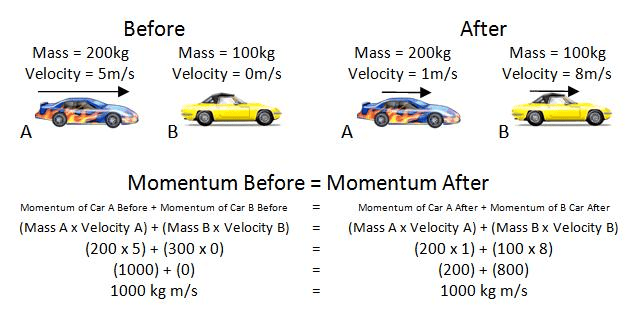

3: Conservation of Linear Momentum – Nature’s Accounting System

The Conservation Principle

In isolated systems where external forces are negligible, total momentum remains constant:

[EQUATION: p⃗total,initial = p⃗total,final, or Σm₁v⃗₁ᵢ = Σm₁v⃗₁f]

This conservation law emerges from Newton’s Third Law and proves remarkably powerful for analyzing complex interactions without knowing detailed force information.

Identifying Isolated Systems

Real systems are never perfectly isolated, but we can often approximate them as such when:

- Collision times are very short (external forces don’t have time to significantly change momentum)

- Internal forces greatly exceed external forces

- We’re analyzing motion in directions where external forces are minimal

Multi-Dimensional Momentum Conservation

Momentum conservation applies independently in each spatial direction:

[EQUATION: p⃗x,initial = p⃗x,final and p⃗y,initial = p⃗y,final and p⃗z,initial = p⃗z,final]

This component-wise conservation enables solving complex two-dimensional collision problems systematically.

Problem-Solving Strategy: Systematic Momentum Analysis

- Define the system: Identify all objects whose interactions you’re analyzing

- Check isolation: Verify that external forces are negligible or perpendicular to motion

- Choose coordinates: Establish consistent positive directions for each dimension

- Apply conservation: Write momentum conservation equations for each direction

- Solve systematically: Use algebra to find unknown quantities

- Verify results: Check that your answers make physical sense

4: Collision Analysis – Elastic vs. Inelastic Interactions

Elastic Collisions: When Kinetic Energy Is Conserved

In perfectly elastic collisions, both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved. These idealized interactions provide insight into fundamental physics principles, though real collisions always involve some energy dissipation.

For one-dimensional elastic collisions between two objects:

[EQUATION: Conservation of Momentum: m₁v₁ᵢ + m₂v₂ᵢ = m₁v₁f + m₂v₂f]

[EQUATION: Conservation of Kinetic Energy: ½m₁v₁ᵢ² + ½m₂v₂ᵢ² = ½m₁v₁f² + ½m₂v₂f²]

Solving these simultaneously yields the elastic collision formulas:

[EQUATION: v₁f = ((m₁-m₂)v₁ᵢ + 2m₂v₂ᵢ)/(m₁+m₂)]

[EQUATION: v₂f = ((m₂-m₁)v₂ᵢ + 2m₁v₁ᵢ)/(m₁+m₂)]

Physics Check: Special Elastic Cases

Analyze these scenarios using the elastic collision formulas:

- Equal masses: Objects exchange velocities

- One object initially at rest with much larger mass: First object bounces back, second barely moves

- One object initially at rest with much smaller mass: First object continues with reduced speed, second moves rapidly

Inelastic Collisions: Real-World Energy Loss

Most real collisions are inelastic, meaning kinetic energy is not conserved due to deformation, sound, heat, and other dissipative processes. However, momentum is still conserved in isolated systems.

Perfectly Inelastic Collisions

In perfectly inelastic collisions, objects stick together after impact:

[EQUATION: m₁v₁ᵢ + m₂v₂ᵢ = (m₁ + m₂)vf, where vf is the common final velocity]

The kinetic energy lost in the collision equals:

[EQUATION: KEₗₒₛₜ = KEᵢ – KEf = ½m₁v₁ᵢ² + ½m₂v₂ᵢ² – ½(m₁ + m₂)vf²]

Real-World Physics: Collision Safety Engineering

Vehicle safety engineers use collision analysis to design crumple zones and safety systems. In head-on collisions, cars are designed to undergo partially inelastic deformation, converting dangerous kinetic energy into relatively safe deformation energy. The momentum principles you’re learning directly contribute to saving lives on highways worldwide.

5: Center of Mass and System Dynamics

Defining Center of Mass

The center of mass represents the average position of a system’s mass distribution:

[EQUATION: x̄cm = (Σmᵢxᵢ)/(Σmᵢ), where x̄cm is center of mass position, mᵢ is individual mass, xᵢ is individual position]

For continuous mass distributions:

[EQUATION: x̄cm = (∫x dm)/(∫dm), where dm represents differential mass elements]

Center of Mass Motion

The center of mass moves as if all external forces act on the total mass concentrated at that point:

[EQUATION: F⃗external = Mtotalācm, where Mtotal is total system mass and ācm is center of mass acceleration]

This principle dramatically simplifies analyzing complex multi-object systems.

Historical Context: Pierre-Simon Laplace and Celestial Mechanics

The center of mass concept proved crucial for understanding planetary motion. Laplace used these principles to demonstrate that the solar system’s center of mass provides a stable reference frame for analyzing planetary orbits, contributing to our modern understanding of celestial mechanics and space navigation.

Internal Forces and Center of Mass

Internal forces between system components cannot change the center of mass motion. This fundamental principle explains why you can’t lift yourself by pulling on your bootstraps – internal forces within your body cannot accelerate your center of mass upward against gravity without external support.

6: Experimental Applications and Laboratory Techniques

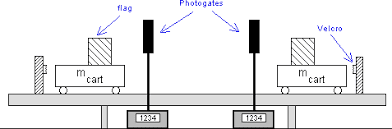

Momentum Conservation Verification

Laboratory investigations typically use air tracks, collision carts, or photo gates to minimize friction and measure velocities accurately. Key experimental considerations include:

Equipment Setup:

- Air tracks reduce friction to negligible levels

- Photo gates measure velocities with high precision

- Video analysis enables detailed motion study

- Force sensors can measure impulse directly

Data Collection Strategies

Effective momentum experiments require:

- Multiple trials to assess measurement uncertainty

- Careful mass measurements using analytical balances

- Velocity measurements both before and after interactions

- Systematic variation of initial conditions

Error Analysis in Momentum Experiments

Common sources of experimental error include:

- Friction forces (even on air tracks)

- Air resistance effects

- Photo gate timing precision

- Cart mass uncertainties

- Human reaction time in manual measurements

[EQUATION: Percent Error = |Experimental Value – Theoretical Value|/Theoretical Value × 100%]

Problem-Solving Strategy: Experimental Design

When designing momentum experiments:

- Identify the specific conservation law you’re testing

- Minimize external forces through careful equipment selection

- Plan multiple measurement techniques for cross-validation

- Consider systematic and random error sources

- Design data analysis procedures before collecting data

7: Advanced Applications – Rockets, Variable Mass, and Explosions

Variable Mass Systems: The Rocket Equation

When mass changes during motion, we must use the more general form of Newton’s Second Law:

[EQUATION: F⃗external = dp⃗/dt = d(mv⃗)/dt = m(dv⃗/dt) + v⃗(dm/dt)]

For rockets expelling mass at constant rate:

[EQUATION: Rocket Equation: MΔv = vexhaust ln(Mi/Mf), where vexhaust is exhaust velocity relative to rocket]

This equation governs all rocket propulsion, from model rockets to interplanetary spacecraft.

Real-World Physics: Space Exploration and Momentum

NASA’s Voyager spacecraft, launched in 1977, continue traveling through interstellar space using momentum gained from gravitational slingshot maneuvers around planets. These gravity assists demonstrate momentum conservation on astronomical scales, enabling spacecraft to reach velocities impossible with rocket fuel alone.

Explosion Analysis

Explosions represent the reverse of perfectly inelastic collisions. An initially stationary or slowly moving object breaks apart into high-speed fragments:

[EQUATION: 0 = Σmᵢv⃗ᵢ (if initially at rest), where the sum includes all explosion fragments]

Multi-Stage Processes

Complex systems often involve sequential momentum conservation applications:

- Multi-stage rockets

- Chain collision sequences

- Particle decay processes

- Gravitational slingshot trajectories

8: Two-Dimensional Collision Analysis

Vector Components in Collisions

Two-dimensional collisions require component-wise momentum conservation:

x-direction: m₁v₁ᵢₓ + m₂v₂ᵢₓ = m₁v₁fₓ + m₂v₂fₓ

y-direction: m₁v₁ᵢᵧ + m₂v₂ᵢᵧ = m₁v₁fᵧ + m₂v₂fᵧ

Glancing Collisions

When objects don’t collide head-on, the collision analysis becomes more complex but follows the same conservation principles. The angle of deflection depends on:

- Mass ratio of colliding objects

- Impact parameter (how off-center the collision is)

- Whether the collision is elastic or inelastic

Physics Check: Billiards Physics

Pool players intuitively use momentum conservation principles. When a cue ball strikes another ball at an angle, both momentum conservation and geometric constraints determine the final trajectories. Professional players develop remarkable intuition for these complex momentum calculations through practice.

Practice Problems Section: Mastering Momentum Calculations

Multiple Choice Problems

Problem 1: A 1200 kg car traveling east at 25 m/s collides with a 1800 kg truck traveling west at 15 m/s. After the perfectly inelastic collision, what is their common velocity?

A) 2.5 m/s east

B) 2.5 m/s west

C) 5.0 m/s east

D) 5.0 m/s west

E) 0 m/s

Solution: Using momentum conservation with east as positive:

Initial momentum = (1200 kg)(25 m/s) + (1800 kg)(-15 m/s) = 30000 – 27000 = 3000 kg⋅m/s

Final momentum = (1200 + 1800)(vf) = 3000 vf

Therefore: vf = 3000/3000 = 1.0 m/s east

Correct Answer: None listed (actual answer is 1.0 m/s east)

Problem 2: A 0.15 kg baseball is pitched horizontally at 40 m/s and is hit straight back at 50 m/s. If the bat and ball are in contact for 0.002 s, what is the average force exerted by the bat on the ball?

A) 3375 N

B) 6750 N

C) 13500 N

D) 27000 N

E) 1350 N

Solution: Using the impulse-momentum theorem:

Δp = m(vf – vi) = (0.15 kg)(50 m/s – (-40 m/s)) = (0.15)(90) = 13.5 kg⋅m/s

F = Δp/Δt = 13.5 kg⋅m/s / 0.002 s = 6750 N

Correct Answer: B) 6750 N

Problem 3: Two identical hockey pucks on frictionless ice collide elastically. Puck A has initial velocity 8.0 m/s east, and puck B is initially at rest. After collision, what are their final velocities?

A) A: 0 m/s, B: 8.0 m/s east

B) A: 4.0 m/s east, B: 4.0 m/s east

C) A: -4.0 m/s east, B: 12.0 m/s east

D) A: 8.0 m/s east, B: 0 m/s

E) A: -8.0 m/s east, B: 16.0 m/s east

Solution: For elastic collision between equal masses where one is initially at rest, they exchange velocities.

vAf = 0 m/s, vBf = 8.0 m/s east

Correct Answer: A) A: 0 m/s, B: 8.0 m/s east

Free Response Problems

Problem 4: A 2.0 kg block moving at 5.0 m/s collides with a 3.0 kg block initially at rest on a frictionless surface. After the collision, the 2.0 kg block moves at 1.0 m/s in the same direction.

a) Find the final velocity of the 3.0 kg block.

b) Is this collision elastic or inelastic? Justify your answer with calculations.

c) If the collision is inelastic, calculate the kinetic energy lost.

Solution:

Part (a): Using conservation of momentum:

m₁v₁ᵢ + m₂v₂ᵢ = m₁v₁f + m₂v₂f

(2.0)(5.0) + (3.0)(0) = (2.0)(1.0) + (3.0)(v₂f)

10.0 = 2.0 + 3.0v₂f

v₂f = 8.0/3.0 = 2.67 m/s

Part (b): Check kinetic energy conservation:

KEᵢ = ½(2.0)(5.0)² + ½(3.0)(0)² = 25.0 J

KEf = ½(2.0)(1.0)² + ½(3.0)(2.67)² = 1.0 + 10.7 = 11.7 J

Since KEᵢ ≠ KEf, the collision is inelastic.

Part (c): Energy lost = KEᵢ – KEf = 25.0 – 11.7 = 13.3 J

Problem 5: A 1500 kg car traveling north at 20 m/s collides with a 2000 kg truck traveling east at 15 m/s at an intersection. The vehicles stick together after the collision.

a) Find the magnitude and direction of their velocity immediately after collision.

b) Calculate the kinetic energy lost in the collision.

c) Determine the impulse experienced by each vehicle.

Solution:

Part (a): Using component-wise momentum conservation:

x-component: (1500)(0) + (2000)(15) = (3500)vfₓ → vfₓ = 30000/3500 = 8.57 m/s

y-component: (1500)(20) + (2000)(0) = (3500)vfᵧ → vfᵧ = 30000/3500 = 8.57 m/s

Magnitude: |vf| = √(8.57² + 8.57²) = 12.1 m/s

Direction: θ = tan⁻¹(8.57/8.57) = 45° north of east

Part (b):

KEᵢ = ½(1500)(20)² + ½(2000)(15)² = 300,000 + 225,000 = 525,000 J

KEf = ½(3500)(12.1)² = 256,708 J

Energy lost = 525,000 – 256,708 = 268,292 J ≈ 268 kJ

Part (c):

Car impulse: Δp⃗car = (1500)(8.57î + 8.57ĵ) – (1500)(20ĵ) = 12,855î – 17,145ĵ N⋅s

Magnitude = √(12,855² + 17,145²) = 21,427 N⋅s = 21.4 kN⋅s

Truck impulse: Δp⃗truck = (2000)(8.57î + 8.57ĵ) – (2000)(15î) = -12,860î + 17,140ĵ N⋅s

Magnitude = 21.4 kN⋅s (Newton’s Third Law confirms equal and opposite impulses)

Experimental Design Problems

Problem 6: Design an experiment to verify momentum conservation using readily available materials in a physics laboratory.

Proposed Experiment:

Objective: Verify momentum conservation in one-dimensional collisions between carts on an air track.

Materials:

- Air track with two collision carts of known masses

- Photo gates connected to timer system

- Various masses to add to carts

- Computer data acquisition system

Procedure:

- Set up air track level and activate air flow

- Install photo gates at measured positions

- Measure cart masses precisely

- Give cart A initial velocity, cart B starts at rest

- Record velocities before and after collision

- Repeat with various mass combinations and initial velocities

- Test both elastic (magnetic repulsion) and inelastic (velcro) collisions

Data Analysis:

Calculate total momentum before and after each collision

Determine percent difference between initial and final momentum

Plot momentum conservation accuracy vs. various parameters

Analyze sources of experimental uncertainty

Expected Results:

Momentum should be conserved within experimental uncertainty (typically ±2%)

Systematic errors might arise from friction, air resistance, or timing precision

9: Impulse and Force Analysis in Detail

Average Force vs. Instantaneous Force

During collisions, forces often vary dramatically with time. The impulse-momentum theorem relates the average force to momentum change:

[EQUATION: F̄avg = Δp/Δt = J/Δt, where F̄avg is average force over time interval Δt]

Understanding this distinction helps analyze real collision data where forces change rapidly.

Force-Time Relationships

Different collision scenarios produce characteristic force-time profiles:

- Hard collisions: High peak forces, short duration

- Soft collisions: Lower peak forces, longer duration

- Constant force: Rectangular force-time profile

- Spring collisions: Sinusoidal or triangular profiles

Common Error Alert: Force Direction and Sign

Students frequently make sign errors when calculating impulse. Remember that force and resulting change in momentum must have consistent signs within your chosen coordinate system. If force opposes motion, both force and momentum change should be negative.

Applications in Sports and Safety

Athletes and safety engineers manipulate collision duration to control forces:

- Catching: Extend arms to increase collision time, reducing peak forces

- Jumping: Bend knees upon landing to extend deceleration time

- Boxing gloves: Increase contact area and duration, reducing pressure and peak force

- Car safety: Crumple zones extend collision duration, reducing forces on occupants

10: Advanced Problem-Solving Techniques

Systematic Problem Analysis Framework

Step 1: System Identification

- Define clearly which objects are included in your system

- Identify all forces: internal vs. external

- Determine if momentum conservation applies

Step 2: Coordinate System Setup

- Choose convenient positive directions for each dimension

- Maintain consistency throughout the problem

- Consider rotating coordinates for angled collisions

Step 3: Conservation Law Application

- Write momentum conservation equations for each direction

- Include energy conservation for elastic collisions

- Apply impulse-momentum theorem when forces are known

Step 4: Mathematical Solution

- Solve algebraically before substituting numbers

- Use appropriate significant figures

- Include proper units in final answers

Step 5: Physical Reasoning Check

- Verify answers make intuitive sense

- Check limiting cases (what happens if masses are very different?)

- Confirm energy relationships for collision types

Problem-Solving Strategy: Complex Multi-Step Problems

For problems involving multiple collisions or interactions:

- Analyze each interaction separately using momentum conservation

- Use final conditions from one collision as initial conditions for the next

- Track total system energy if determining collision types

- Draw clear diagrams showing each stage of the process

Approximation Techniques

When exact solutions become complex:

- Use limiting cases to check reasonableness

- Make appropriate approximations (e.g., neglecting smaller masses)

- Estimate orders of magnitude for verification

- Consider geometric constraints that simplify calculations

11: Rotational Momentum Connections (Preview)

Angular Momentum Analogy

Linear momentum concepts extend naturally to rotational motion:

- Linear momentum: p = mv

- Angular momentum: L = Iω (where I is moment of inertia, ω is angular velocity)

Understanding linear momentum provides essential foundation for mastering rotational dynamics in later units.

Real-World Physics: Figure Skating and Conservation

Figure skaters demonstrate conservation principles dramatically when they pull their arms inward during spins. While this example involves angular momentum conservation, the underlying physics principles mirror linear momentum conservation – isolated systems conserve their momentum quantities.

Rolling Motion Considerations

When objects both translate and rotate, total momentum includes contributions from:

- Translational motion of the center of mass

- Rotational motion about the center of mass

These concepts become crucial in AP Physics C: Mechanics Unit 7 (Rotational Dynamics).

Exam Preparation Strategies: Maximizing Your AP Physics C Score

Common AP Exam Question Types

Type 1: Basic Conservation Applications

- Straightforward collision problems

- One-dimensional momentum conservation

- Simple impulse-momentum calculations

- Exam Strategy: Master the fundamental equations and practice rapid application

Type 2: Multi-Dimensional Analysis

- Two-dimensional collision problems

- Vector component applications

- Complex geometry situations

- Exam Strategy: Always break vectors into components systematically

Type 3: Experimental Design and Analysis

- Laboratory investigation questions

- Data interpretation problems

- Error analysis requirements

- Exam Strategy: Understand common experimental setups and error sources

Type 4: Conceptual Understanding

- Qualitative momentum comparisons

- Graphical interpretation problems

- Real-world application scenarios

- Exam Strategy: Develop strong physical intuition beyond mathematical manipulation

Common Error Alert: Frequent AP Exam Mistakes

- Sign Convention Errors: Inconsistent positive/negative direction usage

- Vector Component Confusion: Mixing up x and y components in 2D problems

- Conservation Law Misapplication: Applying conservation when external forces are significant

- Unit Conversion Mistakes: Forgetting to convert between different unit systems

- Significant Figure Errors: Using incorrect precision in final answers

Calculator Usage Tips

Approved Functions:

- Trigonometric calculations for vector components

- Logarithmic functions for advanced applications

- Statistical functions for data analysis problems

- Strategy: Practice common calculation sequences to maintain speed

Physics Check: Pre-Exam Confidence Builder

Test your readiness with these quick checks:

- Can you state momentum conservation in words and equations?

- Do you know the difference between elastic and inelastic collisions?

- Can you analyze 2D collision problems systematically?

- Are you comfortable with impulse-momentum calculations?

- Do you understand experimental design principles?

If you answered “yes” to all questions, you’re well-prepared for the AP exam!

Mathematical Toolkit: Essential Equations Summary

Core Momentum Relationships

[EQUATION: Linear Momentum: p⃗ = mv⃗]

[EQUATION: Impulse-Momentum Theorem: J⃗ = Δp⃗ = F⃗avgΔt]

[EQUATION: Newton’s Second Law (General): F⃗ = dp⃗/dt]

[EQUATION: Conservation of Momentum: Σp⃗i = Σp⃗f]

Collision Analysis Formulas

[EQUATION: Elastic Collision (1D): v₁f = ((m₁-m₂)v₁ᵢ + 2m₂v₂ᵢ)/(m₁+m₂)]

[EQUATION: Elastic Collision (1D): v₂f = ((m₂-m₁)v₂ᵢ + 2m₁v₁ᵢ)/(m₁+m₂)]

[EQUATION: Perfectly Inelastic: (m₁ + m₂)vf = m₁v₁ᵢ + m₂v₂ᵢ]

Center of Mass Calculations

[EQUATION: Center of Mass Position: x̄cm = (Σmᵢxᵢ)/(Σmᵢ)]

[EQUATION: Center of Mass Motion: F⃗external = Mtotalācm]

Energy-Momentum Relationships

[EQUATION: Kinetic Energy: KE = p²/(2m) = ½mv²]

[EQUATION: Energy Loss (Inelastic): ΔKE = KEᵢ – KEf]

Conclusion and Next Steps: Building Physics Mastery

Synthesis of Unit 4 Concepts

Linear momentum represents one of physics’ most elegant and powerful conservation principles. Through this unit, you’ve learned how momentum conservation emerges from Newton’s laws yet provides simpler solutions to complex interaction problems. The impulse-momentum theorem connects forces and time to momentum changes, while collision analysis reveals how energy and momentum conservation work together to determine motion outcomes.

These concepts form essential foundations for advanced physics topics:

- Rotational Dynamics: Angular momentum conservation

- Fluid Mechanics: Momentum transfer in flowing systems

- Thermodynamics: Molecular momentum and kinetic theory

- Modern Physics: Particle interactions and relativistic momentum

Connecting to Other AP Physics C Units

Unit 3 (Energy): Energy and momentum conservation often work together in collision problems. Understanding both principles enables complete analysis of mechanical interactions.

Unit 5 (Rotation): Angular momentum concepts directly parallel linear momentum, with rotational analogs of all major principles covered in this unit.

Unit 6 (Oscillations): Momentum concepts help analyze energy transfer in oscillating systems and understand resonance phenomena.

Real-World Physics: Career Connections

Momentum principles appear throughout science and engineering careers:

- Aerospace Engineering: Spacecraft trajectory design and rocket propulsion

- Automotive Safety: Crash test analysis and protective system design

- Sports Science: Biomechanical analysis of athletic performance

- Particle Physics: High-energy collision experiments and detector design

- Video Game Development: Realistic physics simulation programming

Additional Resources for Extended Learning:

- College Board AP Physics C Course Description and Sample Questions

- University physics textbooks for deeper mathematical treatment

- Online simulations for visualizing collision scenarios

- Scientific journals for real-world momentum applications

- Professional physics organizations for career exploration

Final Encouragement

Mastering momentum conservation provides you with powerful tools for understanding how our physical world operates. From subatomic particles to galactic collisions, the principles you’ve learned govern interactions across all scales of the universe. The systematic problem-solving approaches and physical intuition you’ve developed will serve you well not only on the AP exam but throughout any future scientific or engineering endeavors.

Remember that physics understanding builds cumulatively – each concept provides foundation for the next. Your investment in truly understanding momentum conservation will pay dividends as you encounter more advanced physics topics. Stay curious, keep practicing, and maintain confidence in your growing physics expertise.

The momentum you’ve built in studying this unit will carry you successfully through the rest of AP Physics C and beyond!

Recommended –