The Physics of Spinning Worlds

Torque and Rotational Dynamics: Have you ever wondered why figure skaters spin faster when they pull their arms in? Or how a helicopter generates enough torque to lift off the ground? Welcome to the fascinating world of rotational motion, where objects spin, twist, and turn according to principles that govern everything from atomic particles to galaxies.

In your daily life, you encounter rotational dynamics constantly. When you open a door, you’re applying torque. When you ride a bicycle, the wheels demonstrate angular velocity and momentum. Even the Earth itself is a massive spinning object with rotational inertia that affects everything from weather patterns to the length of our days.

Unit 5 of AP Physics C: Mechanics takes you beyond linear motion into the rich domain of rotational dynamics. Here, forces become torques, mass becomes moment of inertia, and Newton’s laws transform into their rotational equivalents. This unit builds directly on your understanding of linear mechanics while introducing new concepts that will prepare you for advanced physics and engineering applications.

What makes rotational dynamics particularly exciting is how it connects to cutting-edge technology. The gyroscopes in your smartphone that detect rotation rely on these principles. Wind turbines that generate clean energy operate on torque and rotational dynamics. Even the hard drive in your computer (if it still has one) spins according to the laws you’ll master in this unit.

Learning Objectives: Your Roadmap to Rotational Mastery

By the end of this unit, you should be able to demonstrate mastery of the following College Board-aligned learning objectives:

Conceptual Understanding:

- Explain the relationship between torque, angular acceleration, and moment of inertia

- Analyze rotational motion using energy methods and conservation principles

- Connect linear and angular quantities through radius relationships

- Predict the behavior of rotating systems under various torque conditions

Mathematical Applications:

- Apply Newton’s second law for rotation to solve complex problems

- Calculate moments of inertia for various geometric shapes and mass distributions

- Use conservation of angular momentum to analyze collision and interaction problems

- Employ rotational kinematics equations to describe motion quantitatively

Experimental Skills:

- Design experiments to measure rotational quantities like angular velocity and acceleration

- Analyze data from rotational motion experiments using appropriate mathematical tools

- Evaluate the accuracy and precision of rotational measurements

- Interpret graphs of rotational quantities versus time

Real-World Connections:

- Apply rotational dynamics principles to engineering and technology problems

- Explain natural phenomena involving rotational motion

- Connect rotational concepts to other areas of physics including oscillations and waves

Section 1: Fundamental Concepts – From Points to Rigid Bodies

Understanding rotational dynamics begins with recognizing that we’re shifting from treating objects as point particles to considering them as extended rigid bodies. This transition opens up entirely new possibilities for motion and requires new mathematical tools to describe what we observe.

Angular Position and Displacement

Just as linear motion requires position coordinates, rotational motion needs angular coordinates. Angular position (θ) tells us how far an object has rotated from some reference direction, typically measured in radians. One complete rotation equals 2π radians or 360 degrees.

Angular displacement represents the change in angular position: Δθ = θ_final – θ_initial. Unlike linear displacement, angular displacement for rotations greater than 2π requires careful consideration of direction and number of complete rotations.

PHYSICS CHECK : Why do physicists prefer radians over degrees? Radians create elegant relationships between linear and angular quantities. When θ is in radians, the arc length s = rθ, making calculations much simpler.

Angular Velocity and Acceleration

Angular velocity (ω) describes how fast something rotates, defined as the rate of change of angular position:

[EQUATION: ω = dθ/dt (instantaneous angular velocity)]

[EQUATION: ω_average = Δθ/Δt (average angular velocity)]

Angular velocity is measured in radians per second (rad/s). The direction of angular velocity follows the right-hand rule: point your fingers in the direction of rotation, and your thumb points in the direction of the angular velocity vector.

Angular acceleration (α) describes how angular velocity changes over time:

[EQUATION: α = dω/dt = d²θ/dt² (instantaneous angular acceleration)]

[EQUATION: α_average = Δω/Δt (average angular acceleration)]

Angular acceleration has units of rad/s².

Connection Between Linear and Angular Quantities

The beauty of rotational motion lies in its intimate connection with linear motion. For a point at distance r from the axis of rotation:

[EQUATION: v = rω (tangential velocity)]

[EQUATION: a_tangential = rα (tangential acceleration)]

[EQUATION: a_centripetal = v²/r = rω² (centripetal acceleration)]

These relationships allow us to seamlessly translate between linear and rotational descriptions of motion.

REAL-WORLD PHYSICS: GPS satellites orbit Earth at about 14,000 km/h linear speed, but their angular velocity is only about 2 revolutions per day. The large radius of their orbit (about 26,600 km from Earth’s center) makes the linear speed much larger than what we’d calculate from angular speed alone if we used Earth’s surface as reference.

Rotational Kinematics Equations

Just as linear motion has kinematic equations for constant acceleration, rotational motion has analogous equations for constant angular acceleration:

[EQUATION: ω = ω₀ + αt]

[EQUATION: θ = θ₀ + ω₀t + ½αt²]

[EQUATION: ω² = ω₀² + 2α(θ – θ₀)]

[EQUATION: θ = θ₀ + ½(ω₀ + ω)t]

Notice the perfect analogy with linear kinematics: θ corresponds to x, ω to v, and α to a.

Section 2: Torque – The Rotational Force

If force causes linear acceleration, what causes angular acceleration? The answer is torque, often called the “rotational force,” though it’s more accurately described as the rotational effect of force.

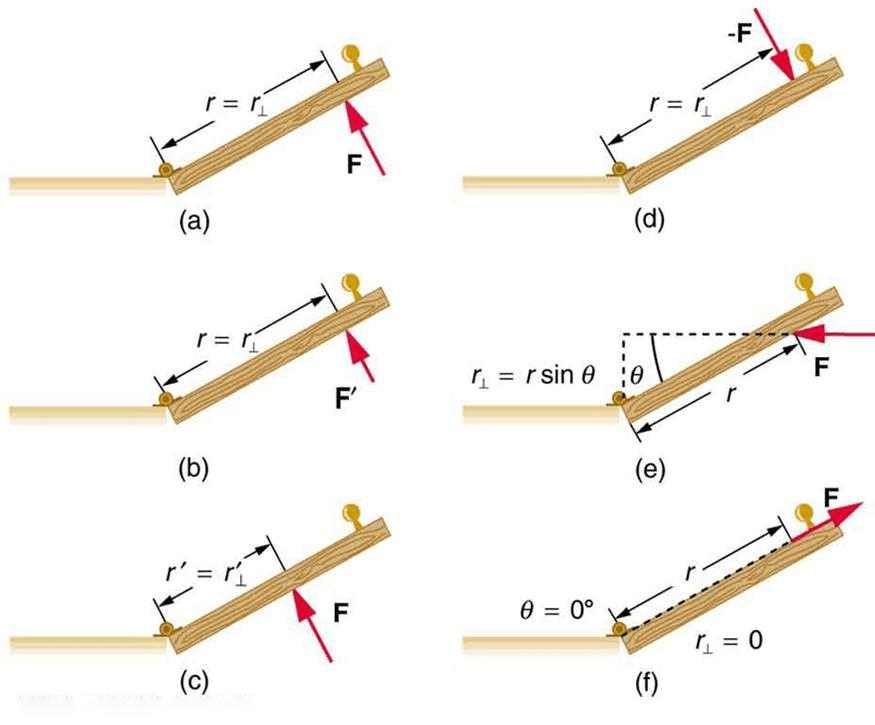

Defining Torque Mathematically

Torque (τ) quantifies a force’s ability to cause rotational motion. It depends not only on the magnitude of the force but also on where and how that force is applied:

[EQUATION: τ = r × F (vector form)]

[EQUATION: τ = rF sin φ (magnitude, where φ is angle between r and F)]

[EQUATION: τ = F⊥r = Fr⊥ (using perpendicular components)]

The lever arm (r⊥) represents the perpendicular distance from the axis of rotation to the line of action of the force. This is why it’s much easier to open a door by pushing near the handle rather than near the hinges – you’re maximizing the lever arm.

PROBLEM-SOLVING STRATEGY: When calculating torque, always identify: 1) The axis of rotation, 2) The point where force is applied, 3) The direction of the force, 4) The lever arm (perpendicular distance). Draw a clear diagram showing these elements before attempting calculations.

Direction of Torque

Torque direction follows the right-hand rule: curl your fingers in the direction the torque would cause rotation, and your thumb points in the torque vector’s direction. Counterclockwise rotation typically corresponds to positive torque, while clockwise rotation corresponds to negative torque.

Multiple Torques and Equilibrium

When multiple torques act on an object, they add vectorially. For an object in rotational equilibrium:

[EQUATION: Στ = 0 (sum of all torques equals zero)]

This condition, combined with the linear equilibrium condition (ΣF = 0), allows us to solve complex statics problems involving both forces and torques.

Torque in Different Situations

Consider these common scenarios where torque plays a crucial role:

- Opening a jar: You grip the lid and apply forces tangentially. The friction between your hands and the lid creates the necessary torque to overcome the jar’s resistance.

- Using a wrench: The longer the wrench handle, the more torque you can apply with the same force. This is why mechanics prefer longer wrenches for stubborn bolts.

- Balancing on a seesaw: Two people of different weights can balance by sitting at different distances from the fulcrum, equalizing their torques about the pivot point.

Section 3: Moment of Inertia – Rotational Mass

Just as mass measures an object’s resistance to linear acceleration, moment of inertia measures resistance to angular acceleration. However, moment of inertia is more complex than mass because it depends not only on how much matter an object contains, but also on how that matter is distributed relative to the axis of rotation.

Defining Moment of Inertia

For a point mass m at distance r from the rotation axis:

[EQUATION: I = mr² (point mass)]

For an extended object, we must sum (or integrate) over all mass elements:

[EQUATION: I = Σmᵢrᵢ² (discrete masses)]

[EQUATION: I = ∫r²dm (continuous mass distribution)]

The moment of inertia has units of kg⋅m².

Common Moments of Inertia

Here are the moments of inertia for common geometric shapes (about axes through their centers):

[EQUATION: I_solid_cylinder = ½MR² (solid cylinder about central axis)]

[EQUATION: I_hollow_cylinder = MR² (thin-walled hollow cylinder)]

[EQUATION: I_solid_sphere = ⅖MR² (solid sphere about diameter)]

[EQUATION: I_hollow_sphere = ⅔MR² (thin-walled hollow sphere)]

[EQUATION: I_rod = 1/12ML² (thin rod about center, perpendicular to rod)]

[EQUATION: I_rod_end = ⅓ML² (thin rod about end, perpendicular to rod)]

Notice how the distribution of mass affects the moment of inertia dramatically. A hollow cylinder has twice the moment of inertia of a solid cylinder with the same mass and radius because more mass is located farther from the axis.

PHYSICS CHECK: Why does a hollow sphere have a larger moment of inertia than a solid sphere? In the hollow sphere, all the mass is at the maximum distance R from the center, while in the solid sphere, much of the mass is closer to the center where r < R.

The Parallel Axis Theorem

When the rotation axis doesn’t pass through an object’s center of mass, we can use the parallel axis theorem:

[EQUATION: I = I_cm + Md² (parallel axis theorem)]

where I_cm is the moment of inertia about the center of mass, M is the total mass, and d is the distance between the two parallel axes.

This theorem is incredibly useful for complex objects where the rotation axis might not be conveniently located through the center of mass.

Physical Meaning and Intuition

Moment of inertia tells us how “spread out” an object’s mass is from the rotation axis. Objects with mass concentrated far from the axis (like a bicycle wheel) have large moments of inertia and are harder to spin up or slow down. Objects with mass concentrated near the axis (like a figure skater with arms pulled in) have small moments of inertia and can spin very rapidly with relatively little angular momentum.

REAL-WORLD PHYSICS: Race car designers carefully consider moment of inertia when designing wheels. Lighter wheels with mass concentrated near the hub reduce the car’s rotational inertia, allowing faster acceleration and better handling. This is why carbon fiber wheels are popular in high-performance vehicles.

Section 4: Newton’s Second Law for Rotation

Just as Newton’s second law governs linear motion, there’s an analogous law for rotational motion that connects torque, moment of inertia, and angular acceleration.

The Rotational Second Law

The fundamental equation of rotational dynamics is:

[EQUATION: Στ = Iα (Newton’s second law for rotation)]

This equation tells us that the net torque on an object equals its moment of inertia times its angular acceleration. Notice the beautiful analogy with F = ma in linear motion.

Deriving the Rotational Second Law

Consider a point mass m at distance r from an axis, subject to a tangential force F:

- Linear acceleration: a = F/m

- Tangential acceleration: a = rα

- Therefore: rα = F/m, which gives F = mrα

- Multiplying both sides by r: Fr = mr²α

- Since τ = Fr and I = mr²: τ = Iα

For extended objects, we sum over all mass elements to get the same result.

Problem-Solving with Rotational Dynamics

When solving rotational dynamics problems, follow this systematic approach:

- Identify the system: What object(s) are rotating? What’s the axis of rotation?

- Draw a diagram: Show all forces, their points of application, and the rotation axis.

- Calculate torques: Find the torque due to each force about the chosen axis.

- Apply Newton’s second law: Set up Στ = Iα.

- Solve for unknowns: Use additional relationships as needed.

PROBLEM-SOLVING STRATEGY: Always choose your rotation axis strategically. Often, choosing an axis where unknown forces act can eliminate those forces from your torque equation, simplifying the solution significantly.

Combined Linear and Rotational Motion

Many real-world problems involve objects that both translate and rotate simultaneously. For example, a rolling wheel undergoes both linear motion of its center of mass and rotation about that center.

For rolling without slipping:

[EQUATION: v_cm = Rω (rolling condition)]

[EQUATION: a_cm = Rα (rolling acceleration condition)]

The total kinetic energy of a rolling object includes both translational and rotational components:

[EQUATION: KE_total = ½Mv_cm² + ½Iω²]

Section 5: Rotational Energy and Work

Energy methods provide powerful alternatives to force-based approaches in rotational mechanics, just as they do in linear mechanics. Understanding rotational energy opens up elegant solution techniques for many complex problems.

Rotational Kinetic Energy

A rotating object possesses kinetic energy due to its motion. For a point mass:

[EQUATION: KE_rot = ½mv² = ½m(rω)² = ½mr²ω² = ½Iω²]

For an extended object, we sum over all mass elements:

[EQUATION: KE_rot = ½Iω² (rotational kinetic energy)]

Notice the perfect analogy with linear kinetic energy: ½mv² becomes ½Iω².

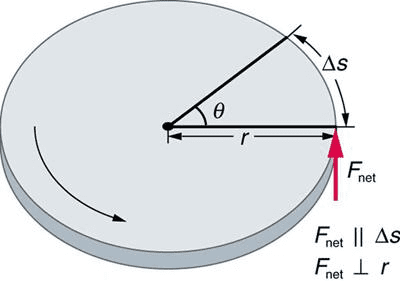

Work Done by Torque

When a torque causes angular displacement, it does work:

[EQUATION: W = ∫τdθ (work done by varying torque)]

[EQUATION: W = τΔθ (work done by constant torque)]

The work-energy theorem for rotation states:

[EQUATION: W_net = ΔKE_rot = ½Iω_f² – ½Iω_i²]

Power in Rotational Motion

Rotational power represents the rate of doing work:

[EQUATION: P = τω (rotational power)]

This is analogous to P = Fv in linear motion.

Energy Conservation in Rotational Systems

Conservation of mechanical energy applies to rotational systems just as it does to linear systems. For a system with both translational and rotational motion:

[EQUATION: E_total = KE_trans + KE_rot + PE = ½Mv_cm² + ½Iω² + mgh]

This approach is particularly powerful for solving problems involving rolling objects on inclines or tracks.

COMMON ERROR ALERT: When applying energy conservation to rolling objects, don’t forget to include both translational and rotational kinetic energy terms. Many students remember ½mv² but forget ½Iω², leading to incorrect answers.

Section 6: Angular Momentum and Its Conservation

Angular momentum serves as the rotational analog of linear momentum and leads to one of physics’ most important conservation laws. Understanding angular momentum is crucial for analyzing everything from atomic structure to planetary motion.

Defining Angular Momentum

For a point particle, angular momentum about an axis is:

[EQUATION: L = r × p = rmv sin φ (vector form)]

[EQUATION: L = mvr⊥ (magnitude using perpendicular distance)]

For a rotating rigid body:

[EQUATION: L = Iω (angular momentum of rigid body)]

Angular momentum has units of kg⋅m²/s.

The Angular Impulse-Momentum Theorem

Just as impulse changes linear momentum, angular impulse changes angular momentum:

[EQUATION: ∫τdt = ΔL (angular impulse-momentum theorem)]

For constant torque:

[EQUATION: τΔt = ΔL = L_f – L_i]

Conservation of Angular Momentum

When the net external torque on a system is zero:

[EQUATION: L_initial = L_final (conservation of angular momentum)]

This conservation law explains many fascinating phenomena:

- Figure skater spin: When a skater pulls in her arms, her moment of inertia decreases. Since angular momentum is conserved, her angular velocity must increase to compensate.

- Bicycle stability: A spinning bicycle wheel resists changes to its orientation due to conservation of angular momentum, helping keep the bike upright.

- Planetary motion: The angular momentum of planets about the Sun remains constant, explaining why planets move faster when closer to the Sun (Kepler’s second law).

REAL-WORLD PHYSICS: The Hubble Space Telescope uses gyroscopes based on conservation of angular momentum for precise pointing. When the spacecraft needs to turn, it spins up gyroscopes in the opposite direction, conserving the total angular momentum of the system.

Angular Momentum in Collisions

Just as linear momentum is conserved in collisions, angular momentum is conserved in rotational collisions when external torques are negligible. This principle helps analyze situations like:

- A spinning disk colliding with a stationary disk

- A person jumping onto a rotating merry-go-round

- Two gears meshing together

[EQUATION: I₁ω₁ + I₂ω₂ = I₁ω₁’ + I₂ω₂’ (angular momentum conservation in collisions)]

Section 7: Advanced Applications and Complex Systems

Real-world rotational dynamics often involves combinations of the principles we’ve studied. This section explores more sophisticated applications that demonstrate the power and elegance of rotational mechanics.

Rolling Motion Analysis

Rolling motion combines translation and rotation in a constrained way. For an object rolling without slipping down an incline:

The constraint equation: v_cm = Rω

The energy equation: mgh = ½mv_cm² + ½Iω²

Substituting the constraint into the energy equation:

mgh = ½mv_cm² + ½I(v_cm/R)²

mgh = ½mv_cm²(1 + I/mR²)

Solving for velocity: v_cm = √(2gh/(1 + I/mR²))

This shows that the acceleration down the incline depends on the object’s moment of inertia. A solid sphere (I = ⅖mR²) will always beat a solid cylinder (I = ½mR²) down the same incline!

Compound Pendulum and Physical Pendulum

A physical pendulum consists of a rigid body pivoting about a point other than its center of mass. The period of oscillation is:

[EQUATION: T = 2π√(I/(mgd))]

where I is the moment of inertia about the pivot point, m is the mass, g is gravitational acceleration, and d is the distance from the pivot to the center of mass.

![Physical pendulum showing pivot point, center of mass, distance d, and restoring torque due to gravity. Include angle θ and angular displacement markers.]](https://solvefyai.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/image-217.png)

Gyroscopic Effects and Precession

When a spinning object (like a gyroscope) is subjected to an external torque, it doesn’t simply tip over as you might expect. Instead, it precesses – the rotation axis itself rotates around another axis.

The rate of precession is given by:

[EQUATION: ω_precession = τ_external/L = τ_external/(Iω_spin)]

This counterintuitive behavior explains why spinning tops precess before falling over and how gyroscopic stabilizers work in ships and aircraft.

Variable Moment of Inertia Systems

Some systems have moments of inertia that change during motion. When this happens, angular velocity must change to conserve angular momentum.

Consider a figure skater spinning with arms extended (large I, smaller ω) who then pulls arms in (smaller I, larger ω). Since L = Iω remains constant:

I₁ω₁ = I₂ω₂

The skater’s rotational kinetic energy actually increases: KE = L²/(2I). As I decreases, KE increases. Where does this extra energy come from? The skater does work against centrifugal effects when pulling her arms inward.

PHYSICS CHECK: Why doesn’t energy conservation prevent the figure skater from spinning faster? The skater does positive work when pulling her arms inward against the centrifugal force, adding energy to the system. Conservation of energy is not violated – mechanical work increases the rotational kinetic energy.

Section 8: Laboratory Applications and Experimental Techniques

Understanding rotational dynamics isn’t complete without examining how we measure and verify these principles experimentally. This section explores key laboratory techniques and investigations that reinforce theoretical understanding.

Measuring Moment of Inertia

Several experimental methods can determine an object’s moment of inertia:

- Oscillation Method: Suspend the object as a physical pendulum and measure its period of oscillation. Use T = 2π√(I/(mgd)) to calculate I.

- Rotational Dynamics Method: Apply a known torque and measure the resulting angular acceleration. Use τ = Iα to determine I.

- Energy Method: Roll the object down an incline and use energy conservation with the rolling constraint to find I.

Angular Velocity and Acceleration Measurements

Modern laboratories use various techniques to measure rotational quantities:

- Photogate timers: Measure the time between spoke passages to calculate angular velocity

- Rotary motion sensors: Provide real-time angular position, velocity, and acceleration data

- Stroboscopic photography: Captures multiple images to analyze rotational motion

- Video analysis: Frame-by-frame analysis of recorded rotational motion

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN: When designing rotational motion experiments, consider: 1) Minimizing friction in bearings, 2) Ensuring rigid body assumptions are valid, 3) Accounting for air resistance at high speeds, 4) Calibrating sensors for angular measurements, 5) Considering systematic errors in timing measurements.

Verification of Conservation Laws

Key experiments demonstrate conservation principles:

- Angular Momentum Conservation: Use a rotating platform with a person holding weights. Measure how angular velocity changes as the person extends or retracts the weights.

- Energy Conservation in Rolling Motion: Compare theoretical predictions with experimental measurements for objects rolling down inclines.

- Collision Studies: Investigate rotational collisions using air pucks on rotating tables or spinning disks on low-friction bearings.

Error Analysis in Rotational Experiments

Common sources of error in rotational dynamics experiments include:

- Bearing friction: Always present but can be minimized with proper lubrication

- Air resistance: Becomes significant at high rotational speeds

- Timing uncertainties: Particularly important for period measurements

- Non-rigid body effects: Real objects may deform slightly under rotation

- Alignment issues: Rotation axes may not be perfectly aligned with theoretical assumptions

Data Analysis Techniques

Rotational motion experiments often produce data that requires specific analysis approaches:

- Linearization: Convert exponential or power-law relationships to linear forms for easier analysis

- Least-squares fitting: Determine best-fit parameters for theoretical models

- Uncertainty propagation: Calculate how measurement uncertainties affect derived quantities

- Graphical analysis: Use slope and intercept methods to extract physical parameters

Section 9: Problem-Solving Mastery – Systematic Approaches

Success in AP Physics C requires not just understanding concepts but also developing systematic problem-solving skills. This section provides frameworks for tackling the most challenging rotational dynamics problems.

The Universal Problem-Solving Framework

Every rotational dynamics problem benefits from this systematic approach:

- Read and Visualize: Carefully read the problem and create a clear mental picture

- Identify and Diagram: Identify the system and draw appropriate diagrams

- List Known and Unknown: Organize given information and identify what to find

- Choose Principles: Decide whether to use force methods, energy methods, or momentum methods

- Apply Mathematics: Set up and solve equations systematically

- Check and Reflect: Verify your answer makes physical sense

Force-Based Approach (τ = Iα)

Use this method when:

- Forces and torques are given or can be easily determined

- You need to find accelerations or forces

- The motion involves changing angular velocity

Systematic steps:

- Choose a rotation axis (often where unknown forces act)

- Draw free-body diagram showing all forces

- Calculate torque due to each force about the chosen axis

- Apply Στ = Iα

- Use constraint equations if needed (like rolling conditions)

- Solve for unknowns

Energy-Based Approach

Use this method when:

- Initial and final states are well-defined

- Forces do work over extended distances/angles

- Conservative forces dominate the motion

Key equations:

- Work-energy theorem: W_net = ΔKE_rot

- Conservation of energy: E_initial = E_final

- Combined kinetic energy: KE_total = ½mv_cm² + ½Iω²

Momentum-Based Approach

Use this method when:

- Analyzing collisions or explosions

- External torques are zero or negligible

- Dealing with impulsive forces

Key principle: L_initial = L_final when Στ_external = 0

PROBLEM-SOLVING STRATEGY: If a problem seems unsolvable with one approach, try switching methods. Force problems sometimes become simple with energy methods, and complex collision problems often yield to momentum conservation. Don’t be afraid to start over with a different approach.

Multi-Object Systems

Complex systems with multiple rotating objects require careful analysis:

- Identify each object: Clearly distinguish different parts of the system

- Choose coordinate systems: Use consistent sign conventions for all objects

- Apply constraints: Use relationships between different objects’ motions

- Write separate equations: Apply rotational dynamics to each object individually

- Solve simultaneously: Combine equations to eliminate unknowns systematically

Common Problem Types and Strategies

- Atwood Machine with Pulley: Include pulley’s rotational inertia and apply Newton’s second law to both masses and pulley

- Rolling Down Inclines: Use energy methods or combine linear and rotational force equations

- Collision Problems: Apply conservation of angular momentum, often combined with conservation of energy

- Variable Moment of Inertia: Use conservation of angular momentum when external torques are zero

- Compound Systems: Break complex systems into simpler parts, analyze each part, then combine results

Practice Problems Section

Multiple Choice Problems

Problem 1: A solid cylinder and a hollow cylinder, both with the same mass M and radius R, are released simultaneously from rest at the top of an incline. Which statement is correct?

A) They reach the bottom at the same time

B) The solid cylinder reaches the bottom first

C) The hollow cylinder reaches the bottom first

D) The one with greater mass reaches the bottom first

E) More information is needed to determine the answer

Solution: The correct answer is B. For rolling without slipping, the acceleration down the incline is a = g sin θ/(1 + I/MR²). The solid cylinder has I = ½MR², giving a = (2/3)g sin θ. The hollow cylinder has I = MR², giving a = (1/2)g sin θ. Since the solid cylinder has greater acceleration, it reaches the bottom first.

Problem 2: A figure skater spinning with angular velocity ω₁ pulls her arms inward, reducing her moment of inertia from I₁ to I₂ = ½I₁. Her new angular velocity ω₂ is:

A) ω₂ = ½ω₁

B) ω₂ = ω₁

C) ω₂ = √2ω₁

D) ω₂ = 2ω₁

E) ω₂ = 4ω₁

Solution: The correct answer is D. Conservation of angular momentum requires I₁ω₁ = I₂ω₂. Since I₂ = ½I₁, we have I₁ω₁ = (½I₁)ω₂, which gives ω₂ = 2ω₁.

Problem 3: A wheel of radius R and moment of inertia I is rotating with angular velocity ω₀. A brake applies a constant frictional torque τ until the wheel stops. The time required to stop is:

A) τ/Iω₀

B) Iω₀/τ

C) τI/ω₀

D) ω₀/(τI)

E) √(Iω₀/τ)

Solution: The correct answer is B. Using τ = Iα and ω = ω₀ + αt with final ω = 0: 0 = ω₀ – (τ/I)t, so t = Iω₀/τ.

Free Response Problems

Problem 4: A uniform rod of mass M = 2.0 kg and length L = 1.2 m can rotate about a frictionless pivot at one end. The rod is initially horizontal and released from rest.

a) Find the moment of inertia of the rod about the pivot point.

b) Find the angular acceleration when the rod is first released.

c) Find the angular velocity when the rod is vertical.

d) Find the linear speed of the free end when the rod is vertical.

Solution:

a) The moment of inertia of a rod about one end is I = ⅓ML² = ⅓(2.0)(1.2)² = 0.96 kg⋅m²

b) When horizontal, the torque due to gravity is τ = Mg(L/2) = (2.0)(9.8)(0.6) = 11.76 N⋅m

Angular acceleration: α = τ/I = 11.76/0.96 = 12.25 rad/s²

c) Using energy conservation from horizontal to vertical:

Initial: PE = Mg(L/2), KE = 0

Final: PE = 0, KE = ½Iω²

Mg(L/2) = ½Iω²

ω = √(MgL/I) = √(2.0 × 9.8 × 1.2/0.96) = √24.5 = 4.95 rad/s

d) Linear speed of free end: v = ωL = (4.95)(1.2) = 5.94 m/s

Problem 5: A solid disk of mass M = 5.0 kg and radius R = 0.30 m is initially at rest. A constant force F = 20 N is applied tangentially to the rim for t = 3.0 s.

a) Find the angular acceleration of the disk.

b) Find the angular velocity after 3.0 s.

c) Find the rotational kinetic energy after 3.0 s.

d) Find the work done by the applied force.

Solution:

a) Moment of inertia: I = ½MR² = ½(5.0)(0.30)² = 0.225 kg⋅m²

Torque: τ = FR = (20)(0.30) = 6.0 N⋅m

Angular acceleration: α = τ/I = 6.0/0.225 = 26.67 rad/s²

b) Angular velocity: ω = αt = (26.67)(3.0) = 80 rad/s

c) Rotational kinetic energy: KE = ½Iω² = ½(0.225)(80)² = 720 J

d) Angular displacement: θ = ½αt² = ½(26.67)(3.0)² = 120 rad

Work done: W = τθ = (6.0)(120) = 720 J

Problem 6: A uniform sphere of mass m and radius R rolls without slipping down an incline of angle θ and height h.

a) Derive an expression for the sphere’s speed at the bottom of the incline.

b) Derive an expression for the acceleration down the incline.

c) Compare this acceleration to that of a sliding block on the same incline.

d) If θ = 30° and h = 2.0 m, find the numerical values for parts (a) and (b).

Solution:

a) Using conservation of energy:

Initial: PE = mgh, KE = 0

Final: PE = 0, KE = ½mv² + ½Iω²

For rolling: v = Rω, so ω = v/R

For a solid sphere: I = ⅖mR²

mgh = ½mv² + ½(⅖mR²)(v/R)²

mgh = ½mv² + ⅕mv²

mgh = (7/10)mv²

v = √(10gh/7)

b) For rolling down an incline:

Forces: mg sin θ (down incline), f (friction up incline)

Linear: ma = mg sin θ – f

Rotational: Iα = fR

Rolling constraint: a = Rα

Combining: ma = mg sin θ – Iα/R = mg sin θ – Ia/(R²)

a(m + I/R²) = mg sin θ

a = mg sin θ/(m + I/R²) = g sin θ/(1 + I/(mR²))

For solid sphere: a = g sin θ/(1 + (2/5)) = (5/7)g sin θ

c) Sliding block: a = g sin θ

Rolling sphere: a = (5/7)g sin θ

The rolling sphere has 5/7 the acceleration of a sliding block.

d) For θ = 30°, h = 2.0 m:

v = √(10 × 9.8 × 2.0/7) = √28 = 5.29 m/s

a = (5/7) × 9.8 × sin(30°) = (5/7) × 9.8 × 0.5 = 3.5 m/s²

Experimental Design Problems

Problem 7: Design an experiment to verify that the moment of inertia of a solid cylinder is I = ½MR².

Solution:

Use the inclined plane method:

Equipment: Solid cylinder, inclined plane with adjustable angle, photogate timers, measuring tape, scale

Procedure:

- Measure the cylinder’s mass M and radius R

- Set up incline at angle θ and measure height h and distance s

- Release cylinder from rest at top and measure time t to reach bottom

- Calculate experimental acceleration: a = 2s/t²

- Compare with theoretical prediction: a = (5/7)g sin θ

Analysis:

From a = (5/7)g sin θ, we can derive that this implies I = ½MR²

If experimental acceleration matches theory within uncertainty, the moment of inertia formula is verified.

Sources of error: Friction, air resistance, measurement uncertainties, non-perfect rolling

Controls: Use smooth surfaces, minimize air currents, repeat trials, ensure pure rolling

Advanced Problem-Solving Techniques

Problem 8: A yo-yo consists of two solid disks of radius R and mass M connected by an axle of radius r and negligible mass. A string is wound around the axle. When released, the yo-yo falls while the string unwinds.

a) Find the acceleration of the yo-yo’s center of mass.

b) Find the tension in the string.

c) Compare the yo-yo’s motion to that of a freely falling object.

Solution:

a) The yo-yo has both translational and rotational motion.

Forces on center of mass: Mg – T = Ma (downward positive)

Torque about center of mass: Tr = Iα (string unwinds, so positive)

Constraint (string doesn’t slip): a = rα

Moment of inertia: I = 2(½MR²) = MR² (two solid disks)

From constraint: α = a/r

From torque equation: T = Iα/r = MR²a/(r²) = M(R²/r²)a

Substituting into force equation:

Mg – M(R²/r²)a = Ma

Mg = Ma + M(R²/r²)a = Ma(1 + R²/r²)

a = g/(1 + R²/r²) = gr²/(r² + R²)

b) Tension: T = M(R²/r²)a = MgR²/(r² + R²)

c) Free fall acceleration is g, while yo-yo acceleration is gr²/(r² + R²)

Since R > r typically, the yo-yo falls slower than a freely falling object

The ratio is r²/(r² + R²) < 1

Problem 9: A bicycle wheel of mass M and radius R is spinning with angular velocity ω₀ when it’s placed on the ground. Initially, the wheel slides on the ground with kinetic friction coefficient μ.

a) Find the motion equations during the sliding phase.

b) Determine when rolling without slipping begins.

c) Find the final rolling velocity.

Solution:

a) During sliding phase:

Linear motion: Ma_cm = μMg (friction accelerates center of mass)

So: a_cm = μg (forward)

Rotational motion: Iα = -μMgR (friction opposes rotation)

For solid disk: I = ½MR²

So: α = -μMgR/(½MR²) = -2μg/R (deceleration)

Velocities as functions of time:

v_cm(t) = μgt (starts from zero)

ω(t) = ω₀ – (2μg/R)t

b) Rolling begins when v_cm = Rω:

μgt = R[ω₀ – (2μg/R)t] = Rω₀ – 2μgt

μgt + 2μgt = Rω₀

3μgt = Rω₀

t = Rω₀/(3μg)

c) Final rolling velocity:

v_final = μg × Rω₀/(3μg) = Rω₀/3

This result can also be found using conservation of angular momentum about the contact point, since there’s no torque about that point during sliding.

Exam Preparation Strategies

Understanding the AP Physics C Format

The AP Physics C: Mechanics exam consists of:

- 35 multiple choice questions (45 minutes, 50% of score)

- 3 free response questions (45 minutes, 50% of score)

Unit 5 (Torque and Rotational Dynamics) typically comprises 10-15% of the exam content.

Key Formulas to Memorize

While the AP exam provides a formula sheet, you should memorize these relationships for quick recall:

Essential equations:

- τ = rF sin φ = Iα

- L = Iω (for rigid bodies)

- KE_rot = ½Iω²

- Rolling condition: v = Rω

- Common moments of inertia (disk, sphere, rod)

Common Exam Question Types

- Comparative Motion: Questions asking you to compare the motion of different objects (sphere vs cylinder rolling down inclines)

- Energy Conservation: Problems involving objects rolling or rotating where energy methods are most efficient

- Angular Momentum Conservation: Collision problems, variable moment of inertia situations

- Combined Motion: Objects that both translate and rotate simultaneously

- Experimental Analysis: Laboratory-based questions involving data interpretation and experimental design

Test-Taking Strategies

For Multiple Choice:

- Eliminate obviously incorrect answers first

- Use dimensional analysis to check answer choices

- Look for limiting cases that make the problem simpler

- Don’t spend more than 90 seconds per question initially

For Free Response:

- Always start with a clear diagram

- Show all work symbolically before substituting numbers

- Explicitly state the physics principles you’re using

- Check that your final answer has correct units and reasonable magnitude

- If you make an error early, subsequent work can still earn partial credit

COMMON ERROR ALERT: Many students forget to include rotational kinetic energy when applying conservation of energy to rolling objects. Always ask yourself: “Is this object rotating?” If yes, include ½Iω² in your energy equation.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Conceptual Errors

- Confusing torque and force: Remember that torque depends on both force magnitude and lever arm. A large force applied close to the rotation axis can produce less torque than a small force applied far away.

- Forgetting the rolling constraint: When objects roll without slipping, always use v = Rω. Many problems become unsolvable if you forget this relationship.

- Incorrect moment of inertia: Double-check which axis of rotation you’re using. The moment of inertia changes dramatically with axis location.

- Mixing up angular and linear quantities: Always check units. Angular velocities have units of rad/s, not m/s.

Mathematical Errors

- Sign convention problems: Establish clear positive directions for both linear and angular quantities at the start of each problem.

- Forgetting to square the radius: In I = mr², many students write I = mr, leading to incorrect calculations.

- Unit conversion errors: Be careful converting between degrees and radians. Most physics equations require radians.

- Energy conservation mistakes: When objects both translate and rotate, the total kinetic energy includes both ½mv² and ½Iω² terms.

Problem-Solving Errors

- Choosing inappropriate methods: Learn to recognize when energy methods are more efficient than force methods, and vice versa.

- Incomplete constraint analysis: In complex systems, identify all constraint relationships between different parts.

- Ignoring friction: In rolling problems, friction is often crucial for providing the torque needed for rotation.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Congratulations! You’ve now explored the rich and fascinating world of rotational dynamics. From the fundamental concepts of angular velocity and acceleration to the sophisticated applications of angular momentum conservation, you’ve built a comprehensive understanding of how objects rotate and spin in our universe.

Key Takeaways

The beauty of rotational dynamics lies in its elegant parallels with linear mechanics. Every concept you mastered in linear motion – Newton’s laws, energy, momentum – has a rotational analog that follows similar mathematical patterns but reveals new physical insights. This parallelism isn’t coincidental; it reflects deep symmetries in the laws of physics that extend far beyond introductory mechanics.

Remember these crucial insights as you continue your physics journey:

- Moment of inertia is more than rotational mass: It encodes how mass is distributed in space, making it a geometric property as much as a dynamic one.

- Conservation laws are incredibly powerful: Angular momentum conservation explains phenomena from figure skating to planetary motion, demonstrating the universality of physical principles.

- Energy methods often provide elegant solutions: When forces are complex or unknown, energy approaches can cut through mathematical complexity to reach answers efficiently.

- Real-world applications are everywhere: From the gyroscopes in your phone to the turbines generating electricity, rotational dynamics principles are embedded in modern technology.

Connecting to Broader Physics

The concepts you’ve learned here prepare you for advanced topics throughout physics:

- Quantum mechanics: Angular momentum becomes quantized, leading to atomic structure and chemical bonding

- Electromagnetism: Magnetic dipoles and spinning charges create magnetic fields through rotational motion

- Relativity: Rotating reference frames reveal new physics about space and time

- Thermodynamics: Rotational degrees of freedom contribute to heat capacity and molecular behavior

- Astrophysics: From stellar rotation to galactic dynamics, these principles govern cosmic phenomena

Study Strategies for Success

As you prepare for the AP exam and beyond:

- Practice regularly: Work problems daily rather than cramming. Rotational dynamics requires developing intuition that comes only through repeated exposure.

- Focus on understanding, not memorization: While you need to know formulas, understanding when and how to apply them is more important than rote memorization.

- Draw diagrams always: Visual representation helps prevent errors and clarifies complex situations. Every problem benefits from a good diagram.

- Check units and limiting cases: These provide quick verification that your answers make physical sense.

- Connect concepts across units: Rotational dynamics builds on kinematics, forces, and energy. Strong connections between units deepen your understanding.

Additional Resources for Continued Learning

- Practice with College Board released exams and questions

- Explore online simulations of rotational motion phenomena

- Connect with study groups and physics communities

- Consider advanced mechanics courses that build on these foundations

- Investigate real-world engineering applications of rotational dynamics

- Explore the historical development of these concepts and the scientists who discovered them

The universe is vast and filled with rotating objects at every scale. You now have the tools to understand their motion. Use them wisely, and continue exploring the elegant mathematics that governs our spinning cosmos.

Beyond the AP Exam

Whether you continue in physics, engineering, or other sciences, the analytical thinking skills you’ve developed here will serve you well. The systematic problem-solving approach – identifying relevant principles, setting up equations, and checking results – applies far beyond physics problems.

The mathematical tools you’ve mastered – vector methods, conservation principles, and energy techniques – appear throughout quantitative sciences. The conceptual frameworks – understanding symmetries, recognizing patterns, and making connections between different phenomena – represent the essence of scientific thinking.

Final Advice

Trust in the power of the principles you’ve learned. When you encounter a challenging problem, take time to think about which fundamental concepts apply. Often, what seems like a complex situation can be understood through the basic principles of torque, angular momentum, or energy conservation.

Remember that physics is not about memorizing solutions to specific problems, but about developing the ability to analyze new situations using fundamental principles. The rotational dynamics concepts you’ve mastered provide tools for understanding everything from molecular motors to galactic rotation curves.

As you move forward in your studies, carry with you the elegance and power of rotational mechanics. These principles have guided scientific discovery for centuries and will continue to unlock new understanding about our rotating, spinning, dynamic universe.

The journey through physics is like learning a new language – the language of nature itself. You’ve now added crucial vocabulary and grammar rules to that language. Use them well, and they will help you read the stories written in the motion of everything from electrons to galaxies.

Good luck on your AP exam, and more importantly, good luck in your continued exploration of the physical world!

Recommended –