The Invisible Helpers Around Us

Have you ever wondered why bread rises when you add yeast? Or how that small packet of curd starter can transform a liter of milk into fresh yogurt overnight? Perhaps you’ve noticed how sewage treatment plants manage to clean dirty water, or how antibiotics help you recover from infections. The answer lies in the fascinating world of microorganisms – tiny living beings that, despite being invisible to the naked eye, play enormous roles in improving human life.

When you wake up in the morning and brush your teeth, eat fermented foods like idli or dosa for breakfast, take antibiotics when sick, or even benefit from cleaner air due to microbial waste treatment, you’re experiencing the incredible ways microbes serve human welfare. These microscopic organisms – bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa – are not just disease-causing agents as many students initially think. In fact, the vast majority of microorganisms are beneficial, working tirelessly as nature’s recyclers, food processors, medicine producers, and environmental cleaners.

This chapter reveals how humans have learned to harness the power of these microscopic allies for food production, industrial manufacturing, waste management, agriculture, and medicine. You’ll discover how traditional fermentation processes that your grandparents used have evolved into modern biotechnological applications that produce life-saving drugs and sustainable energy solutions.

Understanding microbes in human welfare isn’t just academic knowledge – it’s about appreciating the biological foundations of modern civilization and preparing for a future where biotechnology will play an even greater role in solving global challenges like climate change, food security, and disease prevention.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Analyze the role of microorganisms in food processing and preservation, explaining the biochemical basis of fermentation processes used in producing bread, beverages, dairy products, and traditional Indian foods.

- Evaluate industrial applications of microorganisms, including the production of antibiotics, enzymes, vitamins, and other commercially important compounds through controlled fermentation.

- Examine sewage treatment processes, understanding how microorganisms break down organic waste and contribute to water purification at both municipal and domestic levels.

- Assess energy generation from microbes, exploring biogas production, alcohol fermentation for biofuels, and emerging renewable energy technologies.

- Investigate microbes as biocontrol agents, analyzing how beneficial microorganisms can replace harmful chemical pesticides in sustainable agriculture.

- Understand bio-fertilizers and their mechanisms, explaining how nitrogen-fixing bacteria, mycorrhizal fungi, and other microorganisms enhance soil fertility and plant growth.

- Analyze antibiotic production and resistance, examining the discovery, mechanism of action, and responsible use of antibiotics in medical treatment.

- Apply knowledge of microbial processes to solve problems related to biotechnology, environmental management, and sustainable development.

- Connect traditional practices with modern biotechnology, showing how ancient fermentation techniques have evolved into sophisticated industrial processes.

- Evaluate the environmental and economic impact of using microorganisms in various human welfare applications.

1: Understanding Microorganisms and Their Beneficial Roles

The Microbial World: More Friends Than Foes

When most students first encounter microbiology, they often associate microorganisms primarily with diseases. This misconception stems from our natural focus on pathogens in medical contexts. However, the reality is far more fascinating and positive. Of the millions of microbial species that exist, less than 1% are pathogenic to humans. The remaining 99% either live harmlessly around us or actively benefit human welfare.

Microorganisms include bacteria, fungi (yeasts and molds), viruses, protozoa, and algae. Each group has evolved unique metabolic capabilities that humans have learned to exploit. Bacteria can break down complex organic compounds, produce useful chemicals, and even generate electricity. Fungi excel at fermentation processes and producing secondary metabolites like antibiotics. Even some viruses are being engineered as vectors for gene therapy and vaccine development.

Metabolic Diversity: The Key to Microbial Applications

What makes microorganisms so valuable for human welfare is their incredible metabolic diversity. Unlike humans, who rely primarily on oxygen-based respiration and can only digest certain types of food, microorganisms have evolved to utilize virtually every possible energy source and environmental condition.

Some bacteria can grow in the absence of oxygen (anaerobes), making them perfect for biogas production and sewage treatment. Others can fix atmospheric nitrogen, converting it into forms that plants can use. Certain fungi can break down cellulose and lignin, the tough components of plant cell walls, making them invaluable for composting and industrial enzyme production.

This metabolic flexibility means that humans can select specific microorganisms for specific tasks, much like choosing the right tool for a particular job. Need to produce alcohol? Use Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Want to make antibiotics? Employ Penicillium or Streptomyces species. Require nitrogen fixation? Partner with Rhizobium bacteria.

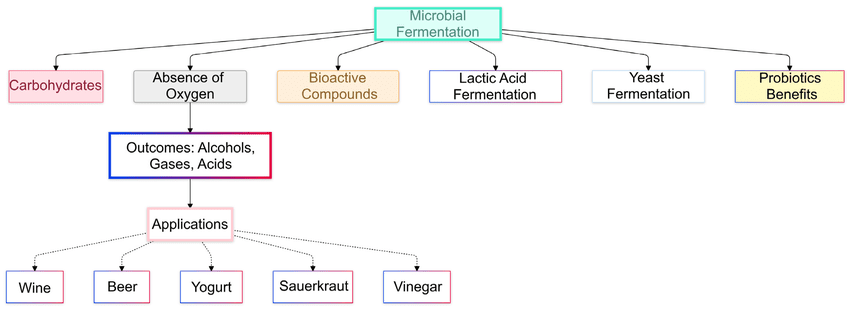

The Concept of Controlled Fermentation

Central to understanding microbes in human welfare is the concept of controlled fermentation. Fermentation is essentially controlled decomposition – allowing microorganisms to break down organic matter under specific conditions to produce desired end products while preventing spoilage or harmful byproduct formation.

Traditional fermentation relied on naturally occurring microorganisms and environmental conditions. Your grandmother making pickle or fermenting rice batter was using wild microorganisms present in the environment. Modern biotechnology has refined this process by using pure cultures of selected microorganisms under carefully controlled temperature, pH, oxygen, and nutrient conditions.

This controlled approach ensures consistent product quality, higher yields, and elimination of harmful contaminants. It’s the difference between hoping your bread will rise properly and knowing it will rise because you’re using a specific strain of yeast under optimal conditions.

Biology Check: Can you explain why most microorganisms are beneficial rather than harmful to humans? Think about evolutionary pressures and ecological relationships.

2: Microbes in Food Processing and Preservation

Traditional Fermentation: Ancient Wisdom, Modern Science

Long before humans understood the science behind fermentation, they discovered that certain foods lasted longer and tasted better when left to “spoil” under specific conditions. This controlled spoilage is actually fermentation – microorganisms converting sugars and other organic compounds into acids, alcohols, and other products that preserve food and create unique flavors.

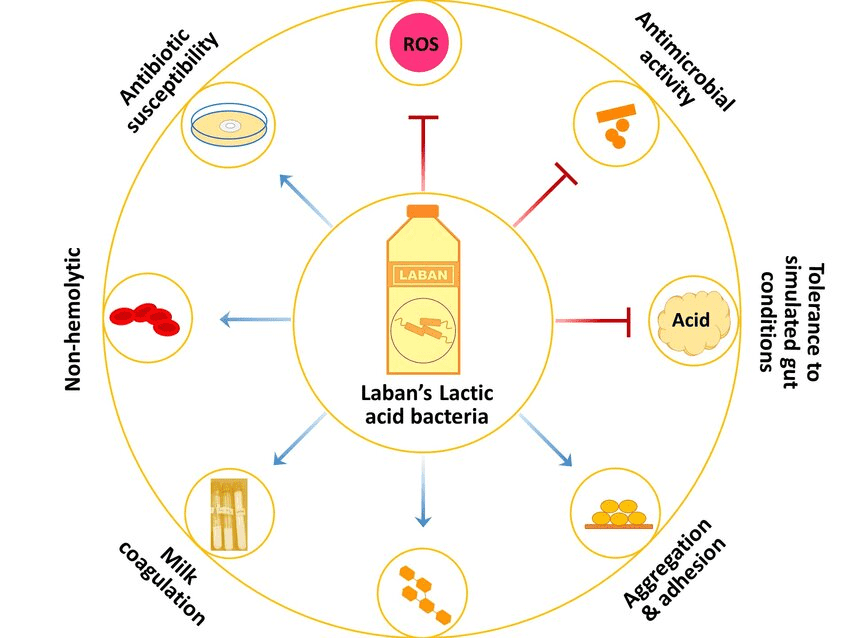

PROCESS: Lactic Acid Fermentation in Dairy Products

When you add a small amount of curd to warm milk, you’re introducing Lactobacillus bacteria. These bacteria consume lactose (milk sugar) and produce lactic acid through the following pathway:

Lactose → Glucose + Galactose (via lactase enzyme) → Pyruvate (via glycolysis) → Lactic Acid (via lactate dehydrogenase)

The lactic acid lowers the pH of milk from about 6.7 to 4.5, causing milk proteins to coagulate and form curd. The acidic environment also prevents growth of harmful bacteria, effectively preserving the milk. This same principle works in making yogurt, cheese, and fermented vegetables like sauerkraut and kimchi.

Bread Making: The Science of Rising Dough

Bread making showcases one of humanity’s most important partnerships with microorganisms. Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker’s yeast) converts sugars in flour into carbon dioxide and ethanol through alcoholic fermentation:

C₆H₁₂O₆ → 2C₂H₅OH + 2CO₂

The carbon dioxide gas gets trapped in the gluten network of the dough, causing it to rise and creating the light, airy texture we associate with good bread. The ethanol evaporates during baking, leaving behind the complex flavors developed during fermentation.

Real-World Biology: Traditional Indian breads like naan and kulcha often use naturally occurring yeasts present in the environment. The fermentation time and temperature affect both the taste and texture of the final product.

Alcoholic Beverages: Controlled Intoxication

The production of alcoholic beverages represents one of humanity’s oldest biotechnological applications. Different microorganisms and substrates produce different types of alcohol:

- Beer: Saccharomyces cerevisiae ferments malted barley

- Wine: Natural yeasts on grape skins ferment grape sugars

- Sake: Aspergillus oryzae breaks down rice starch, then yeasts ferment the sugars

- Traditional drinks: Arrack, feni, and mahua use local yeasts and substrates

The alcohol content depends on factors like yeast strain, temperature, sugar concentration, and fermentation time. Most yeasts stop producing alcohol when levels reach 12-15% because higher concentrations become toxic to the yeast cells themselves.

Industrial Food Production

Modern food processing has scaled up traditional fermentation to industrial levels:

Citric Acid Production: Aspergillus niger grows on sugar-rich media and produces citric acid, widely used as a food preservative and flavor enhancer. This microbial production is more efficient and environmentally friendly than extracting citric acid from citrus fruits.

Enzyme Production: Various microorganisms produce enzymes used in food processing:

- Amylases break down starch in baking and brewing

- Proteases tenderize meat and clarify beverages

- Pectinases improve fruit juice yield and clarity

Single Cell Protein (SCP): Microorganisms like Spirulina and certain yeasts can be grown rapidly on simple substrates to produce protein-rich food supplements, addressing global nutrition challenges.

Common Error Alert: Students often confuse fermentation with simple decomposition. Remember that fermentation is controlled decomposition under specific conditions to produce useful products, while decomposition typically refers to uncontrolled breakdown that makes food spoil.

3: Industrial Production of Enzymes and Chemicals

The Microbial Factory Concept

Think of microorganisms as living factories that can be programmed to produce almost any biological compound. Unlike chemical factories that require high temperatures, pressures, and toxic solvents, microbial factories operate under mild conditions using renewable substrates and producing biodegradable waste.

This biological approach to manufacturing offers several advantages:

- Lower energy requirements

- Reduced environmental pollution

- Ability to produce complex molecules that are difficult to synthesize chemically

- Use of renewable raw materials

- Production of stereochemically pure compounds

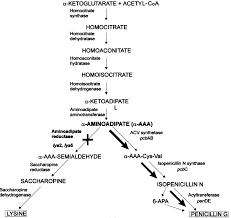

Antibiotic Production: From Accidental Discovery to Life-Saving Industry

Historical Context: Alexander Fleming’s accidental discovery of penicillin in 1928 revealed that Penicillium mold produces a substance that kills bacteria. This serendipitous observation launched the antibiotic era and demonstrated the power of microbial secondary metabolites.

PROCESS: Penicillin Production by Penicillium chrysogenum

Industrial penicillin production involves several carefully controlled steps:

- Strain Development: Selected high-yielding strains of Penicillium chrysogenum

- Medium Preparation: Corn steep liquor, lactose, and specific nutrients

- Fermentation: 6-8 days in large bioreactors with controlled temperature (25°C), pH (6.5), and aeration

- Biosynthesis Pathway: The fungus produces penicillin as a secondary metabolite when growth slows down

- Recovery: Extraction, purification, and crystallization of penicillin

The key insight is that penicillin production occurs during the stationary phase of growth when the organism experiences mild stress. This stress triggers the production of secondary metabolites, many of which have antimicrobial properties – likely an evolutionary adaptation to compete with other microorganisms.

Enzyme Production: Biological Catalysts for Industry

Enzymes are biological catalysts that speed up chemical reactions without being consumed in the process. Industrial enzymes have applications across many sectors:

Detergent Industry:

- Proteases break down protein stains (blood, sweat, food)

- Lipases remove lipid-based stains (grease, oils)

- Amylases handle starch-based stains

Textile Industry:

- Cellulases create the “stone-washed” effect in denim

- Pectinases improve cotton fiber quality

- Catalases remove hydrogen peroxide after bleaching

Food Processing:

- Glucose isomerase converts glucose to fructose for high-fructose corn syrup

- Invertase produces invert sugar for confectionery

- Transglutaminase acts as “meat glue” in processed foods

Process Analysis: Enzyme production typically follows this pattern:

- Screening: Identify microorganisms that produce the desired enzyme

- Optimization: Modify growth conditions to maximize enzyme yield

- Scale-up: Transfer from laboratory to industrial-scale bioreactors

- Recovery: Separate and purify the enzyme from the microbial culture

- Formulation: Stabilize the enzyme for storage and use

Vitamins and Pharmaceuticals

Microorganisms produce many vitamins and pharmaceutical compounds that would be expensive or impossible to synthesize chemically:

Vitamin B12: Only produced by certain bacteria and archaea. Industrial production uses Propionibacterium or Pseudomonas species.

Riboflavin (Vitamin B2): Produced by Bacillus subtilis or engineered yeasts.

Amino Acids:

- Glutamic acid production by Corynebacterium glutamicum (for MSG production)

- Lysine production for animal feed supplements

- Tryptophan for pharmaceutical applications

Modern Biotechnology Applications:

- Human insulin produced in genetically modified E. coli

- Growth hormone from engineered bacteria

- Monoclonal antibodies from hybridoma cell cultures

- Vaccines produced in yeast or bacterial systems

Real-World Biology: The global enzyme market is worth billions of dollars, and most industrial enzymes are now produced by microorganisms rather than extracted from animal or plant sources. This shift represents both economic efficiency and ethical considerations.

4: Sewage Treatment and Environmental Applications

Understanding Sewage: More Than Just Waste

Sewage consists of about 99.9% water and 0.1% solids, but that small percentage of solids contains organic matter, nutrients, and potentially harmful microorganisms that must be removed before the water can be safely returned to the environment. The challenge is removing these contaminants in an economically viable and environmentally sustainable way.

Traditional sewage treatment relies on the same microorganisms that naturally decompose organic matter in rivers, lakes, and soil. The genius of sewage treatment is concentrating and controlling these natural processes to achieve rapid, complete treatment in a confined space.

Primary Treatment: Physical Separation

Primary treatment removes large solids and suspended particles through physical processes:

- Screening: Removes large debris, rags, and objects

- Grit Removal: Settles sand, gravel, and heavy particles

- Primary Sedimentation: Allows heavier solids to settle, forming primary sludge

About 30-40% of suspended solids and 20-30% of BOD (Biochemical Oxygen Demand) are removed in primary treatment. However, dissolved organic matter and nutrients remain in the water.

Secondary Treatment: Biological Purification

This is where microorganisms become the heroes of sewage treatment. Secondary treatment uses controlled biological processes to remove dissolved organic matter and convert it into harmless end products.

PROCESS: Activated Sludge Process

The activated sludge process is the most common secondary treatment method:

- Aeration Tank: Sewage is mixed with activated sludge (a concentrated mixture of microorganisms) and air is pumped in continuously

- Microbial Action: Aerobic bacteria consume organic matter, converting it to CO₂, H₂O, and new bacterial cells

- Secondary Clarifier: The mixture settles; clean water rises to the top while sludge settles to the bottom

- Sludge Recycling: Most sludge returns to the aeration tank to maintain high microbial populations

- Excess Sludge Removal: Surplus sludge is removed for further treatment

Key Microorganisms in Activated Sludge:

- Bacteria: Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Acinetobacter species break down organic compounds

- Protozoa: Paramecium and Vorticella consume bacteria and fine particles

- Rotifers: Multicellular animals that indicate healthy, mature sludge

- Filamentous bacteria: Help form flocs but can cause problems if they overgrow

Biology Check: Why is continuous aeration necessary in the activated sludge process? What would happen if the air supply stopped?

Tertiary Treatment: Advanced Purification

Tertiary treatment removes remaining nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus) that could cause eutrophication in receiving waters:

Nitrogen Removal:

- Nitrification: Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (Nitrosomonas) convert NH₃ to NO₂⁻

- Further oxidation: Nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (Nitrobacter) convert NO₂⁻ to NO₃⁻

- Denitrification: Under anaerobic conditions, denitrifying bacteria reduce NO₃⁻ to N₂ gas

Phosphorus Removal:

- Chemical precipitation using aluminum or iron salts

- Biological phosphorus removal using phosphorus-accumulating organisms

Anaerobic Digestion: Sludge Treatment and Energy Recovery

The sludge removed from primary and secondary treatment contains high concentrations of organic matter that can be converted to useful energy through anaerobic digestion:

PROCESS: Anaerobic Digestion of Sewage Sludge

- Hydrolysis: Complex organic polymers are broken down into simpler compounds

- Acidogenesis: Acid-producing bacteria convert simple compounds to organic acids

- Methanogenesis: Methane-producing archaea convert organic acids to CH₄ and CO₂

The biogas produced (50-70% methane) can be used for heating, electricity generation, or vehicle fuel. The digested sludge is stabilized and can be used as fertilizer.

Environmental Benefits:

- Reduces sludge volume by 40-50%

- Eliminates pathogens through high-temperature digestion

- Produces renewable energy

- Creates valuable soil amendment

Constructed Wetlands: Nature-Based Treatment

Constructed wetlands mimic natural wetland ecosystems to treat wastewater using plants, microorganisms, and natural processes:

- Plants: Cattails, reeds, and other aquatic plants provide oxygen to root zones and uptake nutrients

- Biofilms: Microbial communities on plant roots and substrate surfaces break down organic matter

- Physical filtration: Plant roots and gravel beds filter out suspended solids

This approach is particularly suitable for small communities and requires minimal energy input while providing habitat for wildlife.

Real-World Biology: Many cities now use treated wastewater for irrigation, industrial cooling, and even indirect potable reuse. Singapore’s “NEWater” program demonstrates how advanced treatment can produce water cleaner than many natural sources.

5: Energy Generation from Microbes

The Promise of Microbial Energy

As the world seeks sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels, microorganisms offer promising solutions for renewable energy generation. Microbes can convert various organic wastes into useful energy forms, essentially turning pollution into power while reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The appeal of microbial energy lies in its sustainability cycle: organic waste (which would otherwise decompose and release greenhouse gases) is converted by microorganisms into useful energy, with the process often producing beneficial byproducts like fertilizer or clean water.

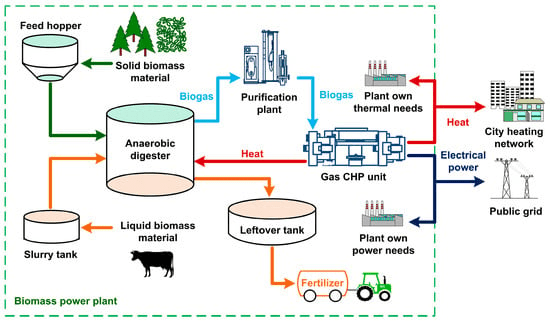

Biogas Production: Turning Waste into Energy

Biogas is a mixture of methane (50-70%) and carbon dioxide (30-50%) produced when organic matter decomposes in the absence of oxygen. This process occurs naturally in swamps, landfills, and animal digestive systems, but humans have learned to control and optimize it for energy production.

PROCESS: Biogas Production Through Anaerobic Digestion

The production of biogas involves a complex community of microorganisms working in sequence:

Stage 1 – Hydrolysis: Hydrolytic bacteria break down complex organic polymers (cellulose, proteins, lipids) into simpler monomers (sugars, amino acids, fatty acids). This step is often rate-limiting because cellulose and lignin are difficult to break down.

Stage 2 – Acidogenesis: Fermentative bacteria convert monomers into organic acids (acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid), alcohols, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide. The environment becomes acidic (pH 4-6).

Stage 3 – Acetogenesis: Acetogenic bacteria convert organic acids and alcohols into acetic acid, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide. These bacteria are sensitive to pH and require neutral conditions.

Stage 4 – Methanogenesis: Methanogenic archaea convert acetic acid and hydrogen/CO₂ into methane and carbon dioxide. Two main pathways exist:

- Acetoclastic methanogenesis: CH₃COOH → CH₄ + CO₂

- Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis: 4H₂ + CO₂ → CH₄ + 2H₂O

Factors Affecting Biogas Production:

- Temperature: Mesophilic (30-40°C) or thermophilic (50-60°C) conditions

- pH: Must be maintained between 6.8-7.2 for optimal methanogen activity

- Carbon/Nitrogen ratio: Optimal ratio of 20-30:1

- Retention time: 15-30 days depending on temperature and substrate

- Mixing: Ensures contact between microorganisms and substrate

Substrate Options:

- Animal manure (cow, pig, poultry)

- Kitchen waste and food processing residues

- Agricultural residues (crop stubble, fruit peels)

- Sewage sludge

- Energy crops (purpose-grown biomass)

Alcohol Production for Biofuels

Ethanol produced by microbial fermentation serves as a renewable fuel that can replace or supplement gasoline. Brazil and the United States have developed large-scale ethanol industries based on sugarcane and corn, respectively.

First-Generation Biofuels: Use food crops like sugarcane, corn, or sugarbeet

- Sugarcane → Yeast fermentation → Ethanol + CO₂

- Corn starch → Amylase digestion → Glucose → Yeast fermentation → Ethanol

Second-Generation Biofuels: Use agricultural waste and non-food biomass

- Cellulosic ethanol from crop residues, wood chips, and dedicated energy crops

- Requires pretreatment to break down lignin and make cellulose accessible

- Uses cellulase enzymes and specialized yeasts that can ferment both glucose and xylose

Process Analysis for Cellulosic Ethanol:

- Pretreatment: Steam, acid, or alkali treatment to disrupt plant cell walls

- Enzymatic hydrolysis: Cellulase and hemicellulase enzymes break down cellulose and hemicellulose to sugars

- Fermentation: Engineered yeasts or bacteria convert sugars to ethanol

- Distillation: Separate ethanol from water and other components

- Dehydration: Remove remaining water to produce fuel-grade ethanol

Microbial Fuel Cells: Direct Electricity Generation

Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) represent a fascinating technology where certain bacteria directly generate electricity as they consume organic matter. This process mimics bacterial respiration but uses an electrode instead of oxygen as the final electron acceptor.

PROCESS: Electricity Generation in Microbial Fuel Cells

- Anode Chamber: Electrogenic bacteria (like Geobacter or Shewanella species) oxidize organic matter, releasing electrons and protons

- Electron Transfer: Electrons flow through an external circuit to the cathode, generating electrical current

- Cathode Chamber: Electrons combine with protons and oxygen to form water

- Proton Exchange: A membrane allows protons to move from anode to cathode while preventing oxygen from reaching the anode

Applications of MFCs:

- Small-scale power generation for remote sensors

- Wastewater treatment with simultaneous energy recovery

- Biosensors for detecting organic pollutants

- Powering electronic devices in resource-limited settings

Advantages:

- Direct conversion of organic matter to electricity

- Operation at ambient temperature and pressure

- No combustion or greenhouse gas emissions

- Can use various organic wastes as fuel

Current Limitations:

- Low power output compared to conventional fuel cells

- High cost of materials (especially membranes and electrodes)

- Need for further research to improve efficiency

Real-World Biology: Some companies are developing MFC systems for treating wastewater while generating electricity. Though power output is still low, the dual benefit of waste treatment and energy production makes this technology economically attractive.

Hydrogen Production by Microorganisms

Hydrogen is considered a clean fuel because its combustion produces only water. Several microorganisms can produce hydrogen through different metabolic pathways:

Dark Fermentation: Certain bacteria (Clostridium, Enterobacter) produce hydrogen during fermentation of organic matter in the absence of light and oxygen.

Photo-fermentation: Purple non-sulfur bacteria use light energy to produce hydrogen from organic acids.

Bio-photolysis: Cyanobacteria and green algae split water molecules using light energy, producing hydrogen and oxygen.

Microbial Electrolysis Cells: Use electricity and microorganisms to split water into hydrogen and oxygen, with lower energy input than conventional electrolysis.

6: Microbes as Biocontrol Agents

The Problem with Chemical Pesticides

Modern agriculture has relied heavily on synthetic chemical pesticides to control crop pests and diseases. While these chemicals have increased crop yields, they have also created serious problems:

- Environmental persistence: Many pesticides remain in soil and water for years

- Non-target effects: Beneficial insects, soil microorganisms, and wildlife are harmed

- Pesticide resistance: Target pests evolve resistance, requiring stronger chemicals

- Bioaccumulation: Chemicals concentrate in food chains, affecting top predators

- Human health concerns: Exposure to pesticides linked to various health problems

These problems have driven the search for biological alternatives that can control pests without harming the environment or human health.

Understanding Biocontrol: Nature’s Own Pest Management

Biological control, or biocontrol, uses living organisms to control pest populations. This approach is based on the ecological principle that every organism has natural enemies that help keep its population in check. By introducing or enhancing these natural enemies, we can manage pest populations without relying on synthetic chemicals.

Biocontrol agents include:

- Predators: Organisms that hunt and consume pests

- Parasites: Organisms that live on or in pests, weakening or killing them

- Pathogens: Disease-causing microorganisms that infect pests

- Competitors: Organisms that compete with pests for resources

Microbial Biocontrol Agents

Microorganisms offer several advantages as biocontrol agents:

- Can be mass-produced in fermenters

- Easy to apply using conventional spraying equipment

- Specific to target pests, minimizing non-target effects

- Biodegradable and environmentally safe

- Can provide long-term control through establishment in the environment

Bacterial Biocontrol Agents:

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt): Perhaps the most successful microbial biocontrol agent, Bt produces crystal proteins that are toxic to specific insect larvae.

PROCESS: Bt Toxin Mechanism of Action

- Ingestion: Insect larvae consume Bt spores and crystal proteins while feeding on treated plants

- Alkaline activation: The alkaline pH of insect gut dissolves crystal proteins, releasing active toxins

- Receptor binding: Toxins bind to specific receptors on gut epithelial cells

- Pore formation: Toxins create pores in cell membranes, disrupting ion balance

- Cell death: Gut cells die, creating openings for bacterial infection

- Septicemia: Bt bacteria multiply in insect body cavity, causing death within 2-5 days

Specificity: Different Bt strains produce different crystal proteins, each specific to certain insect groups:

- Bt kurstaki: Effective against caterpillars (lepidopteran larvae)

- Bt israelensis: Targets mosquito and black fly larvae

- Bt tenebrionis: Controls beetle larvae (coleopteran)

Advantages of Bt:

- Completely safe for humans, birds, fish, and beneficial insects

- No residue problems on food crops

- Insects cannot easily develop resistance due to multiple toxin mechanisms

- Can be used in organic farming systems

Pseudomonas fluorescens: This bacterium controls various plant diseases through multiple mechanisms:

- Produces antifungal compounds that inhibit pathogenic fungi

- Competes with pathogens for nutrients and space around plant roots

- Induces plant defense responses that make plants more resistant to diseases

- Forms protective biofilms on plant roots

Fungal Biocontrol Agents:

Trichoderma species: These beneficial fungi are among the most widely used biocontrol agents for soil-borne plant diseases.

Mechanisms of Trichoderma Biocontrol:

- Mycoparasitism: Trichoderma hyphae grow toward pathogenic fungi, coil around them, and produce enzymes that break down pathogen cell walls

- Antibiosis: Production of antibiotics and other toxic compounds that inhibit pathogen growth

- Competition: Rapid growth and efficient nutrient utilization outcompete pathogens

- Plant growth promotion: Produces plant hormones and enhances nutrient uptake

- Induced resistance: Triggers plant defense mechanisms that provide systemic protection

Beauveria bassiana: This entomopathogenic fungus infects a wide range of insects and is particularly effective against aphids, whiteflies, and thrips.

PROCESS: Fungal Infection of Insects

- Attachment: Fungal spores adhere to insect cuticle

- Germination: Spores germinate and produce enzymes that break down cuticle

- Penetration: Fungal hyphae penetrate through cuticle into insect body cavity

- Proliferation: Fungus grows throughout insect body, consuming tissues

- Death: Insect dies from nutrient depletion and toxic metabolites

- Sporulation: Fungus emerges from dead insect and produces new spores

Viral Biocontrol Agents:

Nuclear Polyhedrosis Viruses (NPVs): These viruses specifically infect certain insect species and are highly effective against caterpillar pests.

Advantages of viral biocontrol:

- Extremely specific – each virus typically infects only one or a few closely related species

- No harmful effects on non-target organisms

- Can spread naturally through pest populations

- Persist in the environment, providing long-term control

Process Analysis for Implementing Microbial Biocontrol:

- Pest identification: Accurately identify the target pest and understand its biology

- Agent selection: Choose appropriate biocontrol agent based on pest species, crop, and environmental conditions

- Quality control: Ensure biocontrol agent is pure, viable, and properly formulated

- Application timing: Apply when pest is present and environmental conditions favor biocontrol agent survival

- Integration: Combine with other pest management practices for optimal results

- Monitoring: Assess effectiveness and adjust program as needed

Real-World Biology: Many countries now have regulatory frameworks for registering microbial biocontrol agents as biopesticides. The global biopesticide market is growing rapidly as farmers seek sustainable alternatives to synthetic chemicals.

Common Error Alert: Students sometimes think biocontrol agents work as quickly as chemical pesticides. In reality, microbial biocontrol often takes longer to show effects because the agent must establish, reproduce, and gradually reduce pest populations. This slower action is actually an advantage for long-term pest management.

7: Bio-fertilizers and Soil Health

Understanding Soil as a Living Ecosystem

Soil is not just dirt – it’s a complex living ecosystem containing billions of microorganisms in every gram. These microorganisms play crucial roles in nutrient cycling, plant health, and soil structure maintenance. Healthy soil contains bacteria, fungi, protozoa, nematodes, arthropods, and other organisms working together to create conditions that support plant growth.

Unfortunately, intensive agriculture practices including excessive chemical fertilizer use, pesticide applications, and continuous cultivation have disrupted these natural soil ecosystems. Chemical fertilizers provide immediate nutrition to plants but don’t feed soil microorganisms, leading to gradual decline in soil biological activity and long-term fertility problems.

Bio-fertilizers represent a return to biological approaches for soil fertility management, using beneficial microorganisms to enhance plant nutrition and soil health naturally.

The Nitrogen Cycle and Biological Nitrogen Fixation

Nitrogen is often the limiting nutrient for plant growth, despite making up 78% of the atmosphere. The problem is that atmospheric nitrogen (N₂) has a triple bond that plants cannot break. Only certain microorganisms possess the enzyme nitrogenase, which can convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia that plants can use.

PROCESS: Biological Nitrogen Fixation

The nitrogenase enzyme complex catalyzes the reduction of atmospheric nitrogen:

N₂ + 8H⁺ + 8e⁻ + 16ATP → 2NH₃ + H₂ + 16ADP + 16Pi

This process requires enormous energy input (16 ATP molecules per N₂ molecule fixed) and is extremely sensitive to oxygen, which irreversibly inactivates nitrogenase. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria have evolved various strategies to protect nitrogenase from oxygen while providing the energy needed for fixation.

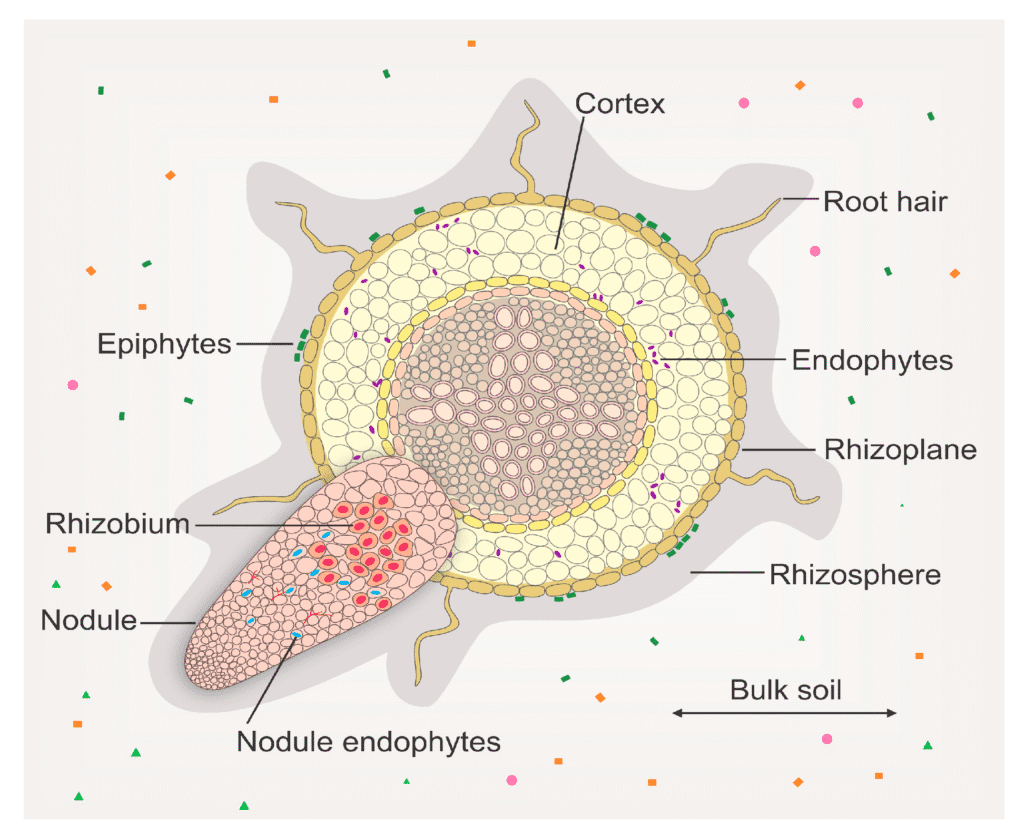

Rhizobium: The Classic Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixer

The relationship between Rhizobium bacteria and leguminous plants (beans, peas, clover, alfalfa) represents one of the most important symbioses in agriculture. This partnership allows legumes to grow in nitrogen-poor soils and actually improves soil fertility for subsequent crops.

PROCESS: Rhizobium-Legume Symbiosis Formation

- Recognition: Legume roots release flavonoids that attract specific Rhizobium species

- Infection: Rhizobium bacteria infect root hairs and induce curling

- Infection thread formation: Bacteria multiply inside infection threads that grow toward root cortex

- Nodule initiation: Plant hormones cause cortical cells to divide, forming nodule primordia

- Bacteroid formation: Rhizobium bacteria differentiate into nitrogen-fixing bacteroids

- Leghemoglobin production: Plant produces leghemoglobin (similar to hemoglobin) to maintain low oxygen concentration while allowing oxygen transport for bacterial respiration

- Nitrogen fixation: Bacteroids fix atmospheric nitrogen and provide ammonia to plant

- Carbon supply: Plant provides carbohydrates and other nutrients to bacteria

Specificity: Different Rhizobium species form partnerships with specific legume groups:

- Rhizobium leguminosarum: Peas, beans, lentils

- Rhizobium meliloti: Alfalfa, sweet clover

- Rhizobium japonicum: Soybeans

- Bradyrhizobium: Slow-growing rhizobia for soybeans and other legumes

Benefits of Rhizobium Inoculation:

- Reduces or eliminates need for nitrogen fertilizers

- Improves legume growth and yield

- Increases protein content in legume seeds

- Leaves nitrogen-rich residues for following crops

- Reduces environmental pollution from nitrogen fertilizers

Free-Living Nitrogen Fixers

Several bacteria can fix nitrogen without forming intimate partnerships with plants:

Azotobacter: These aerobic bacteria fix nitrogen in the rhizosphere (root zone) of many crops. They produce a protective slime layer and have high respiratory rates to maintain low internal oxygen concentrations around nitrogenase.

Azospirillum: These bacteria form loose associations with grass roots and can fix significant amounts of nitrogen. They also produce plant growth-promoting substances like auxins and cytokinins.

Clostridium: Anaerobic nitrogen-fixers that work in waterlogged soils, particularly important in rice cultivation.

Blue-green algae (Cyanobacteria): Important nitrogen fixers in aquatic environments and rice fields. Species like Anabaena and Nostoc have specialized cells called heterocysts that provide anaerobic environments for nitrogenase while the rest of the filament conducts photosynthesis.

Mycorrhizal Fungi: The Root Partners

Mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, creating networks that enhance plant nutrition and stress tolerance. About 90% of plant species form mycorrhizal associations in nature.

Types of Mycorrhizae:

Arbuscular Mycorrhizae (AM): Fungi penetrate root cortical cells and form tree-like structures called arbuscules where nutrient exchange occurs. These fungi are particularly important for phosphorus uptake.

Ectomycorrhizae: Fungi form a sheath around fine roots and penetrate between cortical cells without entering them. Common in forest trees like pines, oaks, and birches.

PROCESS: Mycorrhizal Nutrient Exchange

- Fungal network: Mycorrhizal fungi extend far beyond the root system, accessing nutrients in larger soil volumes

- Phosphorus solubilization: Fungi produce enzymes and acids that release phosphorus from soil minerals and organic matter

- Nutrient transport: Fungi transport phosphorus, nitrogen, and trace elements to plant roots

- Carbon exchange: Plants provide carbohydrates (up to 20% of photosynthetic products) to fungi

- Water transport: Fungal hyphae help plants access water during dry periods

- Disease protection: Mycorrhizal fungi can protect plants from root pathogens

Benefits of Mycorrhizal Inoculation:

- Dramatically improves phosphorus uptake (up to 10-fold increase in some cases)

- Enhances uptake of zinc, copper, and other micronutrients

- Improves drought tolerance

- Reduces transplant shock in seedlings

- Protects against certain soil-borne diseases

- Improves soil structure through hyphal networks

Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria

Soil contains large amounts of phosphorus, but most is in forms that plants cannot use. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria convert insoluble phosphates into soluble forms that plants can absorb.

Mechanisms of Phosphate Solubilization:

- Acid production: Bacteria produce organic acids (citric, gluconic, oxalic) that dissolve mineral phosphates

- Enzyme production: Phosphatase enzymes release phosphorus from organic compounds

- Chelation: Organic acids form complexes with metals (iron, aluminum) that bind phosphorus

Important Genera:

- Bacillus: Soil bacteria that solubilize both mineral and organic phosphates

- Pseudomonas: Produce various organic acids and enzymes

- Aspergillus and Penicillium: Fungi that excel at organic phosphate mineralization

Potassium-Mobilizing Bacteria

Potassium is the third major plant nutrient, and soil bacteria can help mobilize potassium from mineral sources:

- Bacillus mucilaginosus: Produces acids and enzymes that weather potassium-bearing minerals

- Frateuria aurantia: Mobilizes potassium through organic acid production

Application and Management of Bio-fertilizers

Quality Control: Bio-fertilizer effectiveness depends on:

- Viable microbial populations (minimum 10⁸ cells per gram for most products)

- Proper storage conditions (cool, dry, protection from direct sunlight)

- Shelf life management (most products effective for 6-12 months)

- Absence of contaminating microorganisms

Application Methods:

- Seed treatment: Coating seeds with microbial inoculant before planting

- Seedling root dip: Treating seedling roots before transplanting

- Soil application: Mixing inoculant with soil or compost

- Liquid application: Applying microbial suspension through irrigation systems

Factors Affecting Success:

- Soil conditions: pH, moisture, temperature, and chemical composition affect microbial survival

- Plant species: Some plants form better associations than others

- Competition: Indigenous microorganisms may compete with introduced strains

- Chemical inputs: Some pesticides and fertilizers can harm beneficial microorganisms

Real-World Biology: India has become a leader in bio-fertilizer production and use, with government programs promoting their adoption to reduce chemical fertilizer dependence and improve soil health. Studies show that combined use of bio-fertilizers with reduced chemical fertilizers can maintain yields while improving soil biological activity.

Biology Check: Why do legume crops often leave soil more fertile than when they were planted? Think about the nitrogen cycle and plant-microbe partnerships.

8: Antibiotics – Production, Mechanism, and Responsible Use

The Discovery That Changed Medicine

Before antibiotics, simple bacterial infections could be fatal. A small cut might lead to sepsis and death. Pneumonia, tuberculosis, and other bacterial diseases killed millions annually. The discovery and development of antibiotics represents one of the greatest medical advances in human history, turning previously fatal infections into treatable conditions.

Alexander Fleming’s observation in 1928 that Penicillium mold killed bacteria in a contaminated culture dish led to the development of penicillin, the first widely used antibiotic. This discovery launched the “golden age” of antibiotic development, during which most of our current antibiotics were discovered and developed.

Understanding How Antibiotics Work

Antibiotics are antimicrobial compounds that either kill bacteria (bactericidal) or stop their growth (bacteriostatic). They work by targeting specific cellular processes that are essential for bacterial survival but different enough from human cells to avoid harming the patient.

Major Mechanisms of Antibiotic Action:

1. Cell Wall Synthesis Inhibition

Bacterial cell walls contain peptidoglycan, a unique polymer not found in human cells. Several antibiotics target cell wall synthesis:

PROCESS: Penicillin Mechanism of Action

Penicillin blocks the final step in peptidoglycan synthesis by inhibiting transpeptidase enzymes (also called penicillin-binding proteins). Here’s what happens:

- Normal cell wall synthesis: Bacteria continuously build and repair their cell walls using transpeptidase to cross-link peptidoglycan chains

- Penicillin binding: Penicillin mimics the natural substrate and binds irreversibly to transpeptidase

- Cross-linking prevention: With transpeptidase blocked, new peptidoglycan cannot be properly cross-linked

- Osmotic pressure: Water enters the bacterial cell due to osmotic pressure

- Cell lysis: The weakened cell wall cannot withstand osmotic pressure, causing the bacterium to burst and die

This mechanism explains why penicillin is most effective against rapidly growing bacteria (which are actively synthesizing cell walls) and why it doesn’t harm human cells (which lack cell walls).

Other cell wall inhibitors:

- Cephalosporins: Similar mechanism to penicillin but effective against different bacteria

- Vancomycin: Binds to peptidoglycan precursors, preventing their incorporation

- Bacitracin: Interferes with cell wall precursor transport

2. Protein Synthesis Inhibition

Bacterial ribosomes (70S) differ from human ribosomes (80S), allowing selective targeting:

Streptomycin and aminoglycosides: Bind to the 30S ribosomal subunit, causing misreading of mRNA and production of defective proteins

Chloramphenicol: Binds to the 50S subunit and blocks peptide bond formation

Tetracyclines: Prevent tRNA from binding to the ribosome, stopping protein synthesis

3. DNA/RNA Synthesis Inhibition

Quinolones (like ciprofloxacin): Inhibit bacterial DNA gyrase, preventing DNA replication and transcription

Rifamycin: Blocks bacterial RNA polymerase, preventing mRNA synthesis

4. Cell Membrane Disruption

Polymyxins: Disrupt bacterial cell membranes, causing cell contents to leak out

5. Metabolic Pathway Inhibition

Sulfonamides: Block folic acid synthesis by competing with para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA)

Industrial Production of Antibiotics

Most antibiotics are produced by microorganisms, particularly bacteria and fungi that naturally produce these compounds as secondary metabolites to compete with other microorganisms in their environment.

PROCESS: Industrial Penicillin Production

Modern penicillin production involves sophisticated fermentation technology:

- Strain development: High-yielding mutant strains of Penicillium chrysogenum are used, selected through decades of improvement programs

- Medium preparation: Complex medium containing:

- Carbon source: Lactose or glucose

- Nitrogen source: Corn steep liquor (rich in amino acids and vitamins)

- Phosphorus and sulfur sources

- Trace elements and growth factors

- Fermentation process:

- Phase 1 (0-40 hours): Rapid growth phase with high oxygen supply

- Phase 2 (40-120 hours): Production phase with controlled nutrient feeding

- Phase 3 (120-180 hours): Maximum production with careful monitoring

- Environmental controls:

- Temperature: 25-27°C (optimal for Penicillium growth)

- pH: 6.5-7.0 (maintained by automatic acid/base addition)

- Dissolved oxygen: >40% saturation (critical for aerobic metabolism)

- Agitation: Continuous mixing for optimal mass transfer

- Precursor feeding: Addition of phenylacetic acid increases penicillin G production

- Recovery and purification:

- Filtration to remove fungal biomass

- Solvent extraction to concentrate penicillin

- Crystallization to produce pure penicillin

- Quality control testing for potency and purity

Modern Biotechnology Approaches:

- Recombinant DNA technology: Genes for antibiotic production are cloned into fast-growing bacteria like E. coli

- Metabolic engineering: Modifying microbial metabolic pathways to increase antibiotic yields

- Synthetic biology: Designing novel antibiotics by combining parts from different biosynthetic pathways

Antibiotic Resistance: The Growing Crisis

Antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria evolve mechanisms to survive exposure to antibiotics. This is a natural evolutionary response, but human activities have accelerated the process dramatically.

Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance:

1. Enzyme Production

- Beta-lactamases: Enzymes that break down penicillin and related antibiotics

- Aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes: Chemically modify streptomycin and related drugs

- Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase: Inactivates chloramphenicol

2. Target Modification

- Altered penicillin-binding proteins: Change shape so penicillin cannot bind effectively

- Modified ribosomes: Prevent antibiotic binding while maintaining normal function

- DNA gyrase mutations: Render quinolone antibiotics ineffective

3. Reduced Permeability

- Outer membrane changes: Reduce antibiotic entry into bacterial cells

- Efflux pump upregulation: Actively pump antibiotics out of cells

4. Alternative Pathways

- Bypass mechanisms: Use alternative enzymes that aren’t inhibited by antibiotics

Factors Contributing to Resistance Development:

Overuse and Misuse:

- Taking antibiotics for viral infections (which they cannot treat)

- Not completing prescribed antibiotic courses

- Using antibiotics preventively without medical supervision

- Self-medication with leftover antibiotics

Agricultural Use:

- Routine antibiotic use in livestock for growth promotion

- Prophylactic use in healthy animals

- Environmental contamination from agricultural runoff

Hospital Settings:

- High antibiotic use creates strong selection pressure

- Immunocompromised patients are vulnerable to resistant organisms

- Cross-contamination between patients

Judicious Use of Antibiotics

Responsible antibiotic use is essential to preserve these life-saving drugs for future generations:

For Healthcare Providers:

- Accurate diagnosis: Use laboratory tests to confirm bacterial infections

- Appropriate selection: Choose the right antibiotic for the specific pathogen

- Correct dosing: Prescribe adequate doses for sufficient duration

- Narrow spectrum when possible: Use targeted antibiotics rather than broad-spectrum drugs

- Infection control: Prevent spread of resistant organisms in healthcare settings

For Patients:

- Take as prescribed: Complete the full course even if feeling better

- Don’t share antibiotics: Each prescription is specific to the individual and infection

- Don’t save leftover antibiotics: Dispose of unused medications properly

- Don’t pressure doctors: Accept that antibiotics won’t help viral infections

- Practice prevention: Vaccination, hand hygiene, and safe food handling reduce infection risk

For Agricultural Use:

- Growth promotion bans: Many countries have banned antibiotic use for growth promotion in livestock

- Prescription requirements: Requiring veterinary prescriptions for agricultural antibiotic use

- Alternative approaches: Probiotics, vaccination, and improved husbandry reduce disease pressure

Global Initiatives:

- Surveillance programs: Monitor antibiotic resistance patterns worldwide

- Research funding: Develop new antibiotics and alternative treatments

- Education campaigns: Raise awareness about appropriate antibiotic use

- Regulatory frameworks: Control antibiotic availability and use

Common Error Alert: Many students think that antibiotic resistance occurs in humans who take antibiotics. In reality, resistance develops in bacteria, not in the human patients. The resistant bacteria can then spread to other people, even those who have never taken antibiotics.

Real-World Biology: Some pharmaceutical companies are developing new business models for antibiotic development, including “Netflix-style” subscription services where governments pay for access to new antibiotics rather than per-dose pricing. This approach recognizes that new antibiotics should be reserved for resistant infections rather than used widely.

Practice Problems Section

Multiple Choice Questions

1. Which of the following microorganisms is primarily responsible for the rising of bread dough?

a) Lactobacillus acidophilus

b) Saccharomyces cerevisiae

c) Aspergillus niger

d) Rhizobium leguminosarum

Detailed Solution:

The correct answer is b) Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is responsible for bread rising through alcoholic fermentation. The yeast converts sugars in flour into carbon dioxide and ethanol:

C₆H₁₂O₆ → 2C₂H₅OH + 2CO₂

The CO₂ gas gets trapped in the gluten network of the dough, causing it to rise and creating the light, airy texture. The ethanol evaporates during baking.

Option a) Lactobacillus acidophilus is used in yogurt production through lactic acid fermentation.

Option c) Aspergillus niger is used for citric acid production.

Option d) Rhizobium leguminosarum is a nitrogen-fixing bacterium that forms symbiotic relationships with leguminous plants.

2. The activated sludge process in sewage treatment primarily relies on:

a) Anaerobic digestion by methanogens

b) Chemical precipitation of pollutants

c) Aerobic decomposition by mixed microbial populations

d) Physical filtration through sand beds

Detailed Solution:

The correct answer is c) Aerobic decomposition by mixed microbial populations.

The activated sludge process is the most common secondary sewage treatment method. It relies on a diverse community of aerobic microorganisms (bacteria, protozoa, and other microbes) that consume dissolved organic matter in the presence of oxygen. The process requires continuous aeration to maintain aerobic conditions, and the microorganisms convert organic pollutants into CO₂, H₂O, and new microbial biomass.

Option a) describes anaerobic digestion, which is used for sludge treatment, not the main activated sludge process.

Option b) describes chemical treatment methods.

Option d) describes tertiary treatment methods.

3. Bacillus thuringiensis is used as a biocontrol agent because it:

a) Competes with insect pests for food resources

b) Produces crystal proteins toxic to specific insect larvae

c) Secretes antibiotics that kill insect pathogens

d) Forms parasitic relationships with pest insects

Detailed Solution:

The correct answer is b) Produces crystal proteins toxic to specific insect larvae.

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) produces crystalline proteins during sporulation that are toxic to specific groups of insect larvae. When ingested by susceptible insects, these proteins are activated in the alkaline gut environment, bind to specific receptors on gut epithelial cells, create pores in cell membranes, and ultimately kill the insect. Different Bt strains produce different crystal proteins with specificity for different insect groups (caterpillars, mosquito larvae, beetle larvae, etc.).

Option a) describes competitive exclusion, not Bt’s primary mechanism.

Option c) is incorrect – Bt doesn’t work by producing antibiotics.

Option d) describes parasitic biocontrol agents, not Bt’s mechanism.

Case Study Analysis Questions

Case Study 1: Antibiotic Production Optimization

A pharmaceutical company is experiencing declining penicillin yields from their Penicillium chrysogenum fermentation process. Laboratory analysis shows healthy fungal growth but low antibiotic production. The fermentation conditions are: temperature 30°C, pH 7.5, dissolved oxygen 60% saturation, glucose as carbon source.

Questions:

a) Identify three possible causes for low penicillin production despite healthy growth

b) Suggest specific modifications to improve penicillin yield

c) Explain why penicillin is produced as a secondary metabolite

Detailed Solutions:

a) Three possible causes for low penicillin production:

- Suboptimal temperature: The current temperature of 30°C is higher than the optimal range for penicillin production (25-27°C). Higher temperatures favor growth over antibiotic production.

- pH too high: pH 7.5 is above the optimal range of 6.5-7.0 for penicillin biosynthesis. Penicillin production is sensitive to pH changes.

- Carbon source issue: Glucose may be causing catabolite repression of penicillin biosynthesis. Lactose is preferred for production phase as it provides slower, more controlled carbon release.

b) Specific modifications to improve yield:

- Reduce temperature to 25°C during the production phase (after initial growth phase)

- Adjust pH to 6.5-6.8 and maintain through automated acid/base addition

- Switch to lactose or implement fed-batch glucose feeding to avoid catabolite repression

- Add precursor feeding: Include phenylacetic acid to enhance penicillin G production

- Optimize dissolved oxygen: Maintain at 40-50% saturation for optimal balance between growth and production

c) Penicillin as secondary metabolite:

Penicillin is produced as a secondary metabolite because:

- It’s not essential for basic cellular functions or growth

- Production begins during the stationary phase when growth slows

- It serves as a competitive advantage in natural environments by inhibiting competing microorganisms

- The biosynthetic pathway is activated by stress conditions and nutrient limitation

- Secondary metabolite production allows the organism to modify its environment for survival advantage

Experimental Design Questions

Question: Design an experiment to compare the effectiveness of different bio-fertilizers on plant growth

Experimental Design:

Objective: Compare the effectiveness of Rhizobium, Azotobacter, and mycorrhizal fungi bio-fertilizers on the growth of leguminous (pea) and non-leguminous (wheat) plants.

Hypothesis:

- Rhizobium will be most effective for pea plants due to symbiotic nitrogen fixation

- Mycorrhizal fungi will benefit both plant types through improved phosphorus uptake

- Azotobacter will provide moderate benefits to both plants through nitrogen fixation and growth hormones

Materials:

- Seeds: Pea (leguminous) and wheat (non-leguminous)

- Bio-fertilizers: Rhizobium inoculant, Azotobacter culture, mycorrhizal spores

- Sterilized potting soil low in nitrogen and phosphorus

- Identical pots, controlled environment chamber

- Measuring equipment for height, biomass, and nutrient analysis

Experimental Groups (10 plants per group):

For Pea Plants:

- Control (no inoculant)

- Rhizobium only

- Azotobacter only

- Mycorrhizal fungi only

- Rhizobium + Mycorrhizal fungi

- All three bio-fertilizers combined

For Wheat Plants:

- Control (no inoculant)

- Azotobacter only

- Mycorrhizal fungi only

- Azotobacter + Mycorrhizal fungi

Procedure:

- Seed preparation: Surface sterilize seeds, treat with appropriate bio-fertilizers according to manufacturer instructions

- Planting: Plant treated seeds in sterilized, nutrient-poor soil

- Growth conditions: Maintain constant temperature (22°C), photoperiod (12h light/dark), and water content

- Data collection: Measure plant height weekly, final biomass, root nodulation (for peas), and tissue nitrogen/phosphorus content

Controls:

- Negative control: Untreated plants to show baseline growth

- Positive control: Plants grown with chemical fertilizers

- Sterilization control: Verify soil sterilization effectiveness

Expected Results:

- Pea plants with Rhizobium should show highest nitrogen content and growth

- Both plant types with mycorrhizal fungi should show improved phosphorus uptake

- Combined treatments may show synergistic effects

- Wheat plants should not respond to Rhizobium (lack of symbiotic compatibility)

Statistical Analysis: Use ANOVA to compare treatments, with post-hoc tests to identify significant differences between groups.

Data Analysis and Graph Interpretation

Data Analysis Problem: Biogas Production Optimization

A biogas plant monitored methane production over 30 days using different organic substrates. The data shows:

| Day | Cow Manure (m³ CH₄/day) | Kitchen Waste (m³ CH₄/day) | Mixed Substrate (m³ CH₄/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 3.2 |

| 10 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 6.8 |

| 15 | 6.2 | 5.1 | 8.9 |

| 20 | 7.1 | 4.8 | 9.2 |

| 25 | 6.8 | 4.2 | 8.7 |

| 30 | 6.5 | 3.8 | 8.1 |

Questions:

a) Calculate the peak production rate for each substrate and the day it occurred

b) Explain the different phases of biogas production shown in the data

c) Why does the mixed substrate show higher production than individual substrates?

d) Suggest improvements for sustained production

Detailed Analysis:

a) Peak production rates:

- Cow Manure: 7.1 m³/day on day 20

- Kitchen Waste: 5.1 m³/day on day 15

- Mixed Substrate: 9.2 m³/day on day 20

b) Phases of biogas production:

Lag Phase (Days 1-5): Low production as microbial populations establish and adapt to substrate. Hydrolytic bacteria begin breaking down complex organic matter.

Exponential Phase (Days 5-15): Rapid increase in production as acid-producing bacteria convert simple compounds to organic acids, followed by methanogens converting acids to methane.

Peak Phase (Days 15-20): Maximum production when methanogenic populations are fully established and substrate availability is optimal.

Decline Phase (Days 20-30): Decreasing production as readily available substrate is consumed and inhibitory products may accumulate.

c) Mixed substrate advantages:

- Balanced C/N ratio: Cow manure (high C/N) combined with kitchen waste (lower C/N) provides optimal ratio for microbial growth

- Diverse nutrients: Different substrates provide complementary nutrients and trace elements

- Improved buffering: Mixture maintains optimal pH better than individual substrates

- Synergistic effects: Different microbial populations work together more effectively

- Extended production: As one substrate depletes, others continue providing nutrients

d) Improvements for sustained production:

- Continuous feeding: Add fresh substrate regularly instead of batch loading

- Temperature control: Maintain mesophilic (35°C) or thermophilic (55°C) conditions

- pH monitoring: Keep pH between 6.8-7.2 for optimal methanogen activity

- Mixing: Provide gentle agitation to improve substrate-microbe contact

- Nutrient supplementation: Add trace elements if substrate is deficient

Diagram-Based Questions

Question: Analyze the structure and function of root nodules in nitrogen fixation.

Analysis:

Structural Components:

- Outer cortex: Provides protection and contains vascular connections to root

- Oxygen diffusion barrier: Specialized cells that limit oxygen entry to protect nitrogenase

- Infected zone: Contains plant cells filled with bacteroids (differentiated Rhizobium)

- Uninfected cells: Provide metabolic support and transport functions

- Vascular bundles: Transport fixed nitrogen to plant and carbohydrates to bacteria

Functional Relationships:

- Oxygen paradox solution: Bacteroids need oxygen for respiration but nitrogenase is oxygen-sensitive. Leghemoglobin maintains very low but adequate oxygen levels

- Energy exchange: Plant provides 20-30% of photosynthetic products to support energy-expensive nitrogen fixation

- Nitrogen export: Fixed ammonia is converted to amino acids and exported through vascular system

- Infection control: Plant maintains some uninfected cells to prevent complete takeover by bacteria

This structure represents evolutionary optimization for efficient nitrogen fixation while maintaining plant control over the partnership.

Exam Preparation Strategies

Understanding the CBSE Exam Pattern

The CBSE Class 12 Biology exam typically allocates 6-8 marks to Chapter 8 (Microbes in Human Welfare) through various question formats:

Short Answer Questions (2-3 marks):

- Define concepts and explain basic processes

- Compare different types of microorganisms or applications

- Explain mechanisms of action (antibiotics, bio-fertilizers)

Long Answer Questions (5 marks):

- Detailed explanations of processes (sewage treatment, biogas production)

- Applications of microorganisms in different sectors

- Analysis of biotechnological processes

Application-Based Questions:

- Problem-solving scenarios

- Analysis of experimental data

- Evaluation of biotechnological applications

High-Yield Topics for Exam Focus

Priority 1 (Most Frequently Tested):

- Antibiotic production and mechanism of action – Especially penicillin production process and mechanism

- Sewage treatment processes – Activated sludge process and anaerobic digestion

- Bio-fertilizers – Rhizobium-legume symbiosis, mycorrhizal associations

- Fermentation processes – Bread making, alcohol production, dairy products

Priority 2 (Regularly Tested):

- Biogas production – Process, factors affecting production, advantages

- Biocontrol agents – Bacillus thuringiensis mechanism, advantages over chemical pesticides

- Industrial applications – Enzyme production, citric acid production

- Antibiotic resistance – Causes, prevention, responsible use

Priority 3 (Occasionally Tested):

- Single cell protein – Production and applications

- Microbial fuel cells – Basic principle and applications

- Constructed wetlands – Natural sewage treatment

- Traditional fermented foods – Indian examples and processes

Common Exam Mistakes and Prevention

Mistake 1: Confusing fermentation types

- Error: Mixing up alcoholic and lactic acid fermentation

- Prevention: Remember that alcoholic fermentation produces CO₂ (causes rising), while lactic acid fermentation produces acids (causes souring)

Mistake 2: Incorrect antibiotic mechanisms

- Error: Saying all antibiotics work the same way

- Prevention: Learn specific mechanisms – cell wall (penicillin), protein synthesis (streptomycin), DNA synthesis (quinolones)

Mistake 3: Oversimplifying bio-fertilizer benefits

- Error: Saying Rhizobium works with all plants

- Prevention: Remember specificity – Rhizobium only with legumes, mycorrhizae with most plants, Azotobacter as free-living

Mistake 4: Incomplete sewage treatment description

- Error: Describing only one stage of treatment

- Prevention: Always mention primary (physical), secondary (biological), and tertiary (advanced) treatment stages

Memory Aids and Mnemonics

For Antibiotic Mechanisms:

“Cell Protein DNA Membrane” – Four main targets of antibiotics

- Cell wall (penicillin, cephalosporin)

- Protein synthesis (streptomycin, chloramphenicol)

- DNA synthesis (quinolones, rifamycin)

- Membrane integrity (polymyxins)

For Sewage Treatment Stages:

“Primary Secondary Tertiary” = “Physical Separation, Biological Treatment, Advanced Purification”

For Bio-fertilizer Types:

“Nitrogen Phosphorus Potassium” = “Rhizobium Mycorrhizae Bacillus”

- Nitrogen fixers: Rhizobium, Azotobacter

- Phosphorus solubilizers: Mycorrhizae, phosphate-solubilizing bacteria

- Potassium mobilizers: Bacillus mucilaginosus

Conclusion and Next Steps

Connecting Chapter 8 to the Bigger Picture

As you complete your study of “Microbes in Human Welfare,” it’s important to recognize how this chapter connects to broader themes in biology and your future studies:

Integration with Other CBSE Biology Units:

- Chapter 7 (Evolution): Understanding how microorganisms evolved diverse metabolic capabilities that humans now exploit

- Chapter 9 (Biotechnology Principles): The techniques used to manipulate microorganisms for human benefit

- Chapter 12 (Biotechnology Applications): Advanced applications building on basic microbial processes

- Ecology chapters: Role of microorganisms in biogeochemical cycles and ecosystem functioning

Real-World Relevance:

The knowledge you’ve gained about beneficial microorganisms extends far beyond exam preparation. You now understand:

- How traditional food preservation methods work at the molecular level

- Why antibiotic resistance is a growing global concern

- How biological waste treatment can address environmental challenges

- The potential of microorganisms to provide sustainable solutions for agriculture and energy

Current Research and Future Directions

The field of applied microbiology continues to evolve rapidly. Some exciting developments you might encounter in higher studies or current events include:

Synthetic Biology: Scientists are engineering microorganisms with novel capabilities, such as bacteria that produce pharmaceutical compounds or algae that synthesize biofuels more efficiently than natural organisms.

Microbiome Research: Understanding the complex communities of microorganisms in human bodies, soil, and other environments is revolutionizing medicine and agriculture.

Climate Change Solutions: Microorganisms are being developed to capture carbon dioxide, produce sustainable materials, and remediate environmental damage.

Personalized Medicine: Tailoring antibiotic treatments based on individual patient microbiomes and rapid resistance testing.

Resources for Continued Learning

NCERT Textbook: Remains your primary resource – this guide complements but doesn’t replace careful textbook study

Laboratory Manual: If available, practical exercises reinforce theoretical knowledge

Current Events: Follow science news to see how microbial applications are being used to address current challenges

Online Resources: Educational videos can help visualize complex processes, but verify information against reliable sources

Building Scientific Thinking

As you master this chapter, focus on developing scientific thinking skills that will serve you throughout your academic and professional career:

Critical Analysis: Don’t just memorize facts – understand the logic behind biological processes and the reasoning behind human applications

Problem-Solving: Practice approaching new scenarios by identifying the biological principles involved and thinking through possible solutions

Ethical Considerations: Consider the environmental, social, and economic implications of biotechnological applications

Continuous Learning: Science evolves rapidly – develop habits of staying current with new developments in fields that interest you

Final Encouragement

Microbes in Human Welfare represents one of the most practical and immediately relevant chapters in your biology curriculum. The processes you’ve studied – from the bread rising in your kitchen to the sewage treatment plant cleaning your city’s wastewater – demonstrate the profound ways that biological knowledge improves human life.

As you prepare for your exam, remember that you’re not just memorizing facts for a test. You’re gaining understanding of the biological foundations of modern civilization and developing the scientific literacy needed to address future challenges in healthcare, agriculture, environmental protection, and sustainable development.

The microorganisms you’ve studied – invisible to the naked eye but enormous in their impact – remind us that some of the most important biological processes happen at scales we cannot directly observe. This lesson in looking beyond the obvious, understanding complex systems, and appreciating the interconnectedness of life will serve you well whether you pursue further studies in biology, enter healthcare professions, work in agriculture or environmental sciences, or simply become an informed citizen in an increasingly biotechnological world.

Your mastery of this chapter positions you to understand and contribute to solutions for some of humanity’s greatest challenges. The same principles that allow microorganisms to clean sewage, fix nitrogen, and produce life-saving antibiotics continue to inspire new biotechnological innovations that will shape the future.

Study well, think critically, and remember the incredible potential that lies in understanding and partnering with the microbial world around us.

This comprehensive study guide provides everything you need to excel in CBSE Class 12 Biology Chapter 8. The content balances scientific rigor with accessibility, includes extensive practice problems with detailed solutions, and prepares you for both board exams and competitive entrance tests. Use this guide alongside your NCERT textbook and laboratory manual for complete preparation.

Recommended –