The Blueprint of Life in Your Hands

Every morning when you look in the mirror, you’re witnessing one of biology’s most remarkable phenomena. The color of your eyes, the texture of your hair, your height, and even your susceptibility to certain diseases – all these traits were determined by an intricate molecular code written in a language older than any human civilization. This code, stored in every cell of your body, is DNA – the molecular basis of inheritance.

Consider this: a single strand of DNA from one of your cells, if stretched out, would measure about 2 meters long, yet it’s packed into a nucleus only 6 micrometers in diameter. This biological marvel contains approximately 3.2 billion base pairs of information – enough data to fill 200 telephone directories of 1000 pages each. When you realize that this molecular library is copied with 99.9% accuracy every time a cell divides, you begin to appreciate the sophisticated machinery that governs life itself.

The study of molecular basis of inheritance isn’t just about memorizing structures and processes – it’s about understanding how life perpetuates itself, how genetic diseases arise, how we can engineer crops to feed the world, and how we might one day cure cancer through gene therapy. From the insulin produced by genetically modified bacteria to the COVID-19 vaccines developed using mRNA technology, the principles you’ll learn in this chapter are actively shaping our world.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this comprehensive study guide, you will be able to:

Knowledge and Understanding:

- Identify and describe the molecular structure of DNA and RNA with their functional significance

- Explain the semi-conservative mechanism of DNA replication with experimental evidence

- Understand the central dogma of molecular biology and its exceptions

- Describe the process of transcription and the role of different types of RNA

- Explain the genetic code and its universal nature with degeneracy

- Understand the mechanism of translation and protein synthesis

- Analyze gene expression and regulation using the lac operon model

Application and Analysis:

- Compare and contrast the structure and function of DNA and RNA

- Solve problems related to DNA replication, transcription, and translation

- Interpret experimental data related to molecular genetics

- Analyze the significance of genome projects and their applications

- Understand the principles and applications of DNA fingerprinting

- Connect molecular processes to inheritance patterns and genetic disorders

Evaluation and Synthesis:

- Evaluate the impact of molecular genetics on medicine, agriculture, and forensics

- Synthesize information about gene regulation and its importance in development

- Critically analyze the ethical implications of genetic engineering and genome editing

1. The Search for Genetic Material: Historical Perspective

Frederick Griffith’s Transformation Experiment (1928)

The journey to discover the molecular basis of inheritance began with Frederick Griffith’s elegant experiment using Streptococcus pneumoniae. Working with two strains – the virulent S-type (smooth colonies with polysaccharide capsule) and the non-virulent R-type (rough colonies without capsule) – Griffith made a startling discovery.

When he injected mice with heat-killed S-type bacteria mixed with living R-type bacteria, the mice died. More surprisingly, he recovered living S-type bacteria from the dead mice’s blood. This transformation suggested that some “transforming principle” from the dead S-type had converted the living R-type bacteria.

Real-World Biology: This transformation principle is now used in genetic engineering. When scientists want bacteria to produce human insulin, they use similar transformation techniques to introduce the human insulin gene into bacterial cells.

Avery, MacLeod, and McCarty’s Experiment (1944)

Building on Griffith’s work, this trio systematically identified the transforming principle. They treated the heat-killed S-type bacteria with different enzymes:

- Protease treatment: Transformation still occurred (proteins not the genetic material)

- RNase treatment: Transformation still occurred (RNA not the genetic material)

- DNase treatment: Transformation was blocked (DNA is the genetic material)

This experiment provided the first biochemical evidence that DNA, not protein, carries genetic information.

Hershey and Chase Experiment (1952)

The final confirmation came from Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase using bacteriophage T2. They used radioactive labeling:

- ³²P-labeled DNA: Phosphorus is found in DNA but not in proteins

- ³⁵S-labeled proteins: Sulfur is found in proteins but not in DNA

After allowing the phage to infect E. coli and then removing the protein coats by blending, they found that only the ³²P (DNA) had entered the bacteria and was responsible for producing new phages.

Biology Check: Can you explain why the Hershey-Chase experiment was more definitive than previous experiments? Consider the advantages of using bacteriophages over bacteria.

2. DNA as Genetic Material: Structure and Function

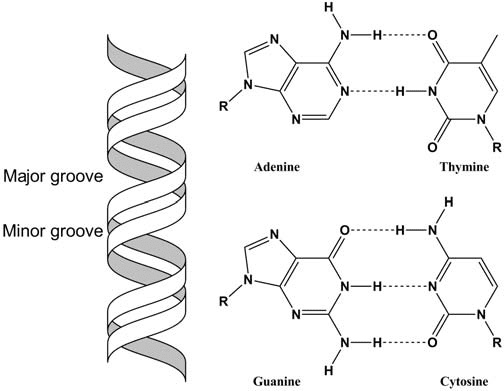

The Double Helix Model

In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick, building on X-ray crystallography data from Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins, proposed the double helix model of DNA. This model revolutionized our understanding of heredity and won them the Nobel Prize.

Chemical Composition of DNA

DNA is a polynucleotide composed of:

- Pentose sugar: 2′-deoxyribose (lacks OH group at 2′ carbon)

- Nitrogenous bases:

- Purines: Adenine (A) and Guanine (G) – larger, double-ring structures

- Pyrimidines: Thymine (T) and Cytosine (C) – smaller, single-ring structures

- Phosphate groups: Create the sugar-phosphate backbone

Key Structural Features

Antiparallel Nature: The two strands run in opposite directions (5′ to 3′ and 3′ to 5′). This antiparallel arrangement is crucial for replication and transcription.

Base Pairing Rules (Chargaff’s Rules):

- A = T (two hydrogen bonds)

- G ≡ C (three hydrogen bonds)

- Amount of purines equals amount of pyrimidines

Major and Minor Grooves: These grooves allow proteins to interact with specific DNA sequences without unwinding the helix.

Common Error Alert: Students often confuse the direction of DNA strands. Remember: 5′ end has a free phosphate group, 3′ end has a free hydroxyl group on the sugar.

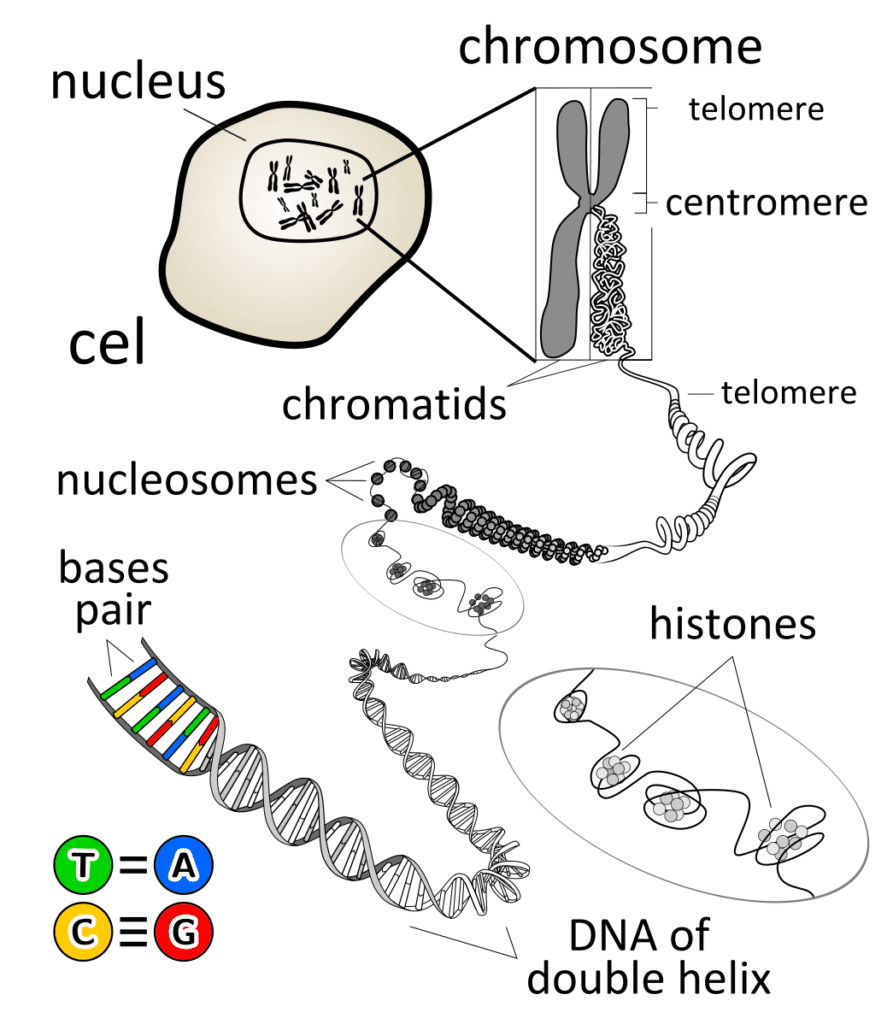

DNA Packaging in Eukaryotes

In eukaryotic cells, DNA packaging is a marvel of biological engineering:

- Nucleosome Level: DNA wraps around histone octamers (2 each of H2A, H2B, H3, H4) forming “beads on a string”

- Chromatin Fiber: Nucleosomes pack with H1 histone to form 30 nm fiber

- Loop Domains: Chromatin fiber forms loops attached to protein scaffold

- Condensed Chromatin: Further compaction during cell division

- Metaphase Chromosome: Maximum condensation (10,000-fold compaction)

3. RNA: The Versatile Nucleic Acid

Structure of RNA

RNA differs from DNA in three key ways:

- Sugar: Ribose (has OH group at 2′ carbon)

- Base: Uracil (U) instead of Thymine

- Structure: Usually single-stranded (can form secondary structures)

Types of RNA and Their Functions

1. Messenger RNA (mRNA):

- Carries genetic information from DNA to ribosomes

- Contains coding sequences (exons) and non-coding sequences (introns in eukaryotes)

- 5′ cap and 3′ poly-A tail in eukaryotes provide stability

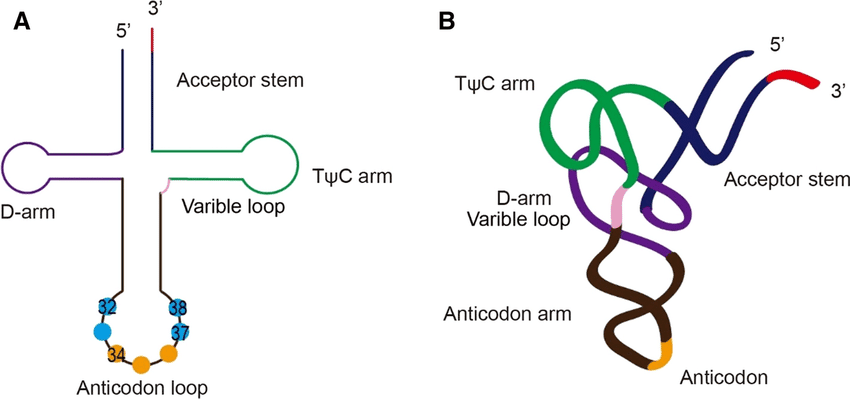

2. Transfer RNA (tRNA):

- Cloverleaf secondary structure with four arms

- Anticodon arm pairs with mRNA codons

- Amino acid attachment site at 3′ end

- Contains modified bases (pseudouridine, dihydrouridine)

3. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA):

- Structural and catalytic component of ribosomes

- Most abundant RNA in cells

- Different sizes: 23S, 16S, 5S in prokaryotes; 28S, 18S, 5.8S, 5S in eukaryotes

Real-World Biology: The discovery that rRNA has catalytic activity (ribozymes) revolutionized our understanding of early life. The “RNA World” hypothesis suggests that RNA preceded DNA and proteins in evolution.

4. DNA Replication: Copying the Blueprint

The Semi-Conservative Model

The Meselson-Stahl experiment (1958) elegantly proved that DNA replication is semi-conservative. They used nitrogen isotopes:

- Heavy nitrogen (¹⁵N) incorporated into DNA bases

- Light nitrogen (¹⁴N) for comparison

After one generation in ¹⁴N medium, all DNA had intermediate density (hybrid), proving that each new DNA molecule contains one old and one new strand.

Mechanism of DNA Replication

[PROCESS: DNA Replication – Step-by-Step Mechanism]

1. Initiation:

- Replication begins at origins of replication (ori)

- Helicase unwinds the double helix

- Single-strand binding proteins prevent re-annealing

- Primase synthesizes RNA primers

2. Elongation:

- DNA polymerase III adds nucleotides in 5′ to 3′ direction

- Leading strand: Continuous synthesis

- Lagging strand: Discontinuous synthesis (Okazaki fragments)

- DNA polymerase I removes primers and fills gaps

- DNA ligase joins Okazaki fragments

3. Termination:

- Replication forks meet

- Primers removed and gaps filled

- Chromosome separation occurs

Key Enzymes in Replication:

- Helicase: Unwinds DNA helix

- Primase: Synthesizes RNA primers

- DNA Polymerase III: Main replicating enzyme

- DNA Polymerase I: Removes primers, fills gaps

- DNA Ligase: Joins DNA fragments

- Topoisomerase: Relieves tension ahead of replication fork

Biology Check: Why is DNA replication called semi-discontinuous? Consider the directionality of DNA polymerase and the antiparallel nature of DNA strands.

Replication in Eukaryotes vs Prokaryotes

| Feature | Prokaryotes | Eukaryotes |

|---|---|---|

| Origins | Single (oriC) | Multiple |

| Speed | ~1000 bp/sec | ~50 bp/sec |

| Polymerases | 3 types (I, II, III) | Multiple (α, δ, ε) |

| Primers | RNA | RNA |

| Processing | Simultaneous | Sequential |

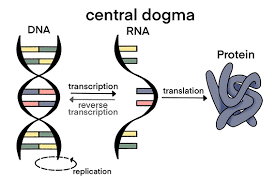

5. Central Dogma: Information Flow in Living Systems

The Central Dogma Concept

Francis Crick proposed the central dogma in 1958: DNA → RNA → Protein. This unidirectional flow of genetic information is fundamental to all life.

Exceptions to Central Dogma

1. Reverse Transcription: RNA → DNA (retroviruses like HIV)

2. RNA Replication: RNA → RNA (RNA viruses)

3. Prions: Protein → Protein (infectious proteins)

Historical Context: The discovery of reverse transcriptase by Howard Temin and David Baltimore revolutionized molecular biology and led to the development of cDNA cloning techniques.

6. Transcription: DNA to RNA Conversion

Process of Transcription

[PROCESS: Transcription – Detailed Mechanism in Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes]

Initiation:

- RNA polymerase binds to promoter region

- In prokaryotes: Sigma factor recognizes -10 and -35 sequences

- In eukaryotes: Transcription factors and RNA polymerase II complex formation

- DNA unwinds to form transcription bubble

Elongation:

- RNA polymerase moves along template strand (3′ to 5′)

- Synthesizes RNA in 5′ to 3′ direction

- Transcription bubble moves with polymerase

- No primer required (unlike DNA replication)

Termination:

- Intrinsic termination: Formation of hairpin loop in RNA

- Extrinsic termination: Rho protein in prokaryotes

- Polyadenylation signal in eukaryotes

Transcription in Eukaryotes vs Prokaryotes

Prokaryotic Transcription:

- Single RNA polymerase

- Coupled transcription-translation

- No RNA processing

- Polycistronic mRNA

Eukaryotic Transcription:

- Three RNA polymerases (I, II, III)

- Nuclear transcription, cytoplasmic translation

- Extensive RNA processing

- Monocistronic mRNA

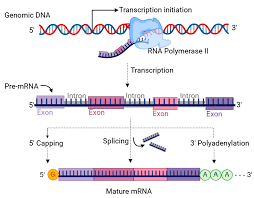

RNA Processing in Eukaryotes

1. 5′ Capping:

- Addition of 7-methylguanosine cap

- Protects mRNA from degradation

- Required for ribosome binding

2. 3′ Polyadenylation:

- Addition of poly-A tail (200-250 adenines)

- Increases mRNA stability

- Enhances translation efficiency

3. Splicing:

- Removal of introns, joining of exons

- Spliceosome machinery (snRNPs)

- Alternative splicing creates protein diversity

7. The Genetic Code: Universal Language of Life

Characteristics of Genetic Code

The genetic code is the set of rules by which DNA/RNA sequences are translated into proteins. It has several important features:

1. Triplet Nature:

- Each codon consists of three nucleotides

- 4³ = 64 possible codons for 20 amino acids

- Provides redundancy and error tolerance

2. Degeneracy:

- Most amino acids coded by multiple codons

- Third position often shows wobble pairing

- Reduces impact of mutations

3. Universality:

- Same code used by all living organisms

- Few exceptions in mitochondria and chloroplasts

- Evidence for common evolutionary origin

4. Non-overlapping:

- Each nucleotide belongs to only one codon

- Reading frame determines protein sequence

5. Comma-less:

- No punctuation between codons

- Continuous reading from start to stop codon

Start and Stop Signals

Start Codon:

- AUG (methionine in eukaryotes, N-formylmethionine in prokaryotes)

- Establishes reading frame

- Recognized by initiator tRNA

Stop Codons:

- UAA (ochre), UAG (amber), UGA (opal)

- No corresponding tRNA

- Recognized by release factors

Biology Check: Why do you think the genetic code is degenerate? How does this property protect organisms from harmful mutations?

Wobble Hypothesis

Proposed by Francis Crick, the wobble hypothesis explains how one tRNA can recognize multiple codons:

- Standard base pairs: A-U, G-C

- Wobble pairs: G-U, I-U, I-A, I-C

- Allows 31 tRNAs to read all 61 sense codons

8. Translation: RNA to Protein Synthesis

The Translation Machinery

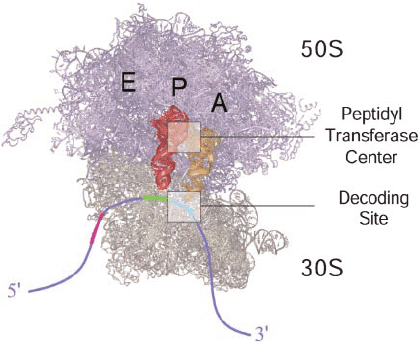

Ribosomes:

- Prokaryotic: 70S (30S + 50S subunits)

- Eukaryotic: 80S (40S + 60S subunits)

- Three binding sites: A (aminoacyl), P (peptidyl), E (exit)

- Catalytic activity resides in rRNA (ribozyme)

Transfer RNA:

- Adapter molecules linking codons to amino acids

- Charged by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases

- High fidelity ensures accurate translation

Translation Process

PROCESS: Translation – Initiation, Elongation, and Termination in Detail

Initiation:

Prokaryotes:

- 30S ribosome binds to Shine-Dalgarno sequence

- fMet-tRNA binds to start codon

- 50S subunit joins to form 70S ribosome

Eukaryotes:

- 40S ribosome binds to 5′ cap

- Scans for start codon (Kozak sequence)

- Met-tRNA and 60S subunit join

Elongation:

- Aminoacyl-tRNA binding: EF-Tu brings aminoacyl-tRNA to A site

- Peptide bond formation: Peptidyl transferase catalyzes bond formation

- Translocation: EF-G moves peptidyl-tRNA to P site, deacylated tRNA to E site

Termination:

- Release factors (RF1, RF2, RF3) recognize stop codons

- Peptide release and ribosome dissociation

- Ribosome recycling factors prepare for next round

Differences in Translation

| Feature | Prokaryotes | Eukaryotes |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm (ribosomes) |

| Ribosomes | 70S | 80S |

| Initiation | Shine-Dalgarno | 5′ cap scanning |

| First amino acid | N-formylmethionine | Methionine |

| Coupling | Transcription-translation | Separate processes |

9. Gene Expression and Regulation

Levels of Gene Regulation

Gene expression can be controlled at multiple levels:

- Transcriptional control: Most important in prokaryotes

- Post-transcriptional control: RNA processing, stability

- Translational control: Ribosome binding, miRNA

- Post-translational control: Protein modification, degradation

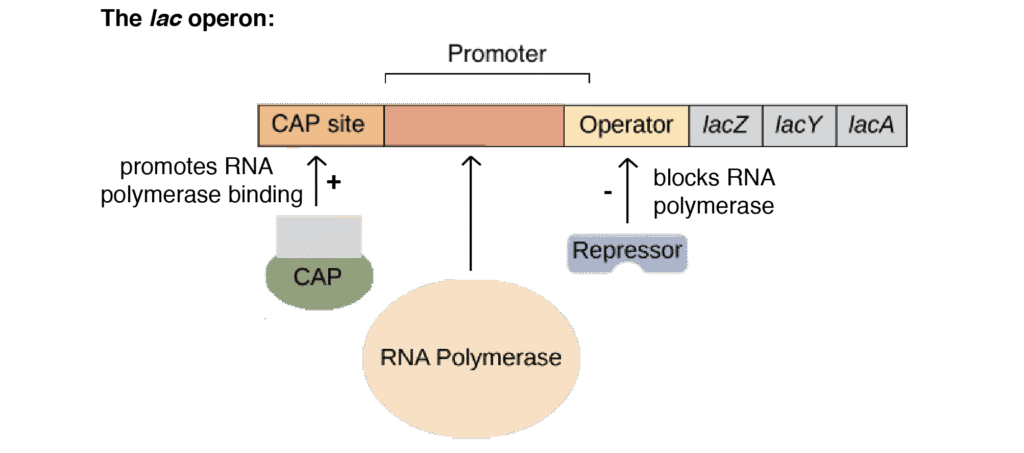

The lac Operon: A Model System

The lac operon in E. coli is a classic example of gene regulation, discovered by François Jacob and Jacques Monod.

Components of lac Operon:

- Structural genes: lacZ (β-galactosidase), lacY (permease), lacA (transacetylase)

- Regulatory elements: Promoter, operator, CAP binding site

- Regulatory genes: lacI (repressor), crp (CAP protein)

lac Operon Regulation

In Absence of Lactose:

- lac repressor (LacI) binds to operator

- RNA polymerase blocked from transcribing genes

- Operon is OFF (repressed state)

In Presence of Lactose:

- Allolactose (inducer) binds to repressor

- Repressor releases from operator

- RNA polymerase can transcribe genes

- Operon is ON (induced state)

Catabolite Repression:

- When glucose is present, cAMP levels are low

- CAP-cAMP complex cannot form

- Even with lactose present, transcription is reduced

- Glucose is preferred carbon source

Real-World Biology: Understanding the lac operon led to the development of inducible expression systems used in biotechnology to produce proteins like human insulin and growth hormone.

Positive vs Negative Control

Negative Control:

- Repressor protein inhibits transcription

- Example: LacI repressor in lac operon

Positive Control:

- Activator protein enhances transcription

- Example: CAP-cAMP complex in lac operon

Common Error Alert: Students often think the lac operon is only under negative control. Remember that it requires both the removal of negative control (repressor) and the presence of positive control (CAP-cAMP) for maximum expression.

10. Human Genome Project and Rice Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP)

Launched in 1990 and completed in 2003, the HGP was one of the most ambitious scientific projects ever undertaken.

Goals and Achievements:

- Map and sequence all human genes (~20,000-25,000 genes)

- Identify genetic variations among individuals

- Develop technologies for genome analysis

- Address ethical, legal, and social implications

Key Findings:

- Human genome contains ~3.2 billion base pairs

- Only ~2% codes for proteins

- Humans share 99.9% genetic similarity

- Alternative splicing creates protein diversity

Methodologies:

- Shotgun sequencing: Random fragmentation and sequencing

- Clone-by-clone approach: Systematic mapping and sequencing

- Bioinformatics: Computer analysis of sequence data

Applications of HGP

Medical Applications:

- Pharmacogenomics: Personalized medicine based on genetic profile

- Gene therapy: Treatment of genetic disorders

- Disease susceptibility: Prediction and prevention

- Diagnostic tests: Genetic screening and counseling

Research Applications:

- Comparative genomics: Understanding evolution

- Functional genomics: Gene function studies

- Proteomics: Protein structure and function

Rice Genome Project

Rice (Oryza sativa) was the first crop plant to be completely sequenced.

Significance:

- Staple food for over half the world’s population

- Model organism for cereal genomics

- Smaller genome (430 million base pairs) than human

Applications:

- Development of high-yield varieties

- Nutritional enhancement (Golden Rice)

- Disease and pest resistance

- Climate adaptation

Current Research: Scientists are now using CRISPR-Cas9 technology to edit rice genes for improved nutrition, including increased vitamin A content and reduced arsenic uptake.

11. DNA Fingerprinting: Genetic Identity

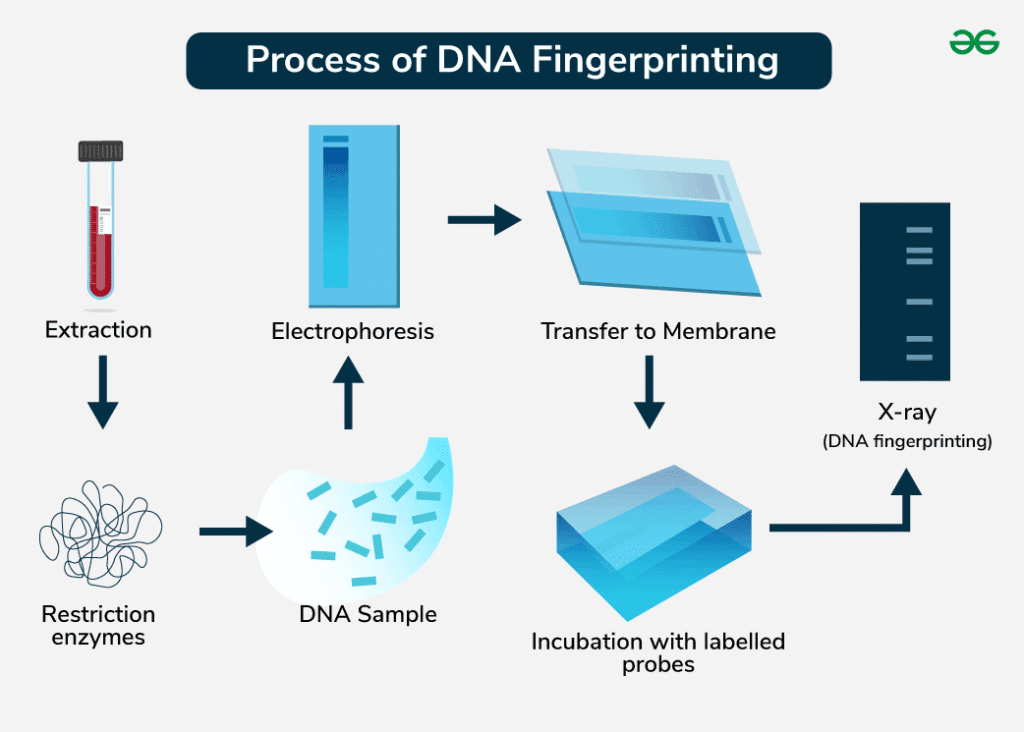

Principles of DNA Fingerprinting

DNA fingerprinting, developed by Alec Jeffreys in 1984, exploits genetic variations between individuals.

Basis:

- Variable Number Tandem Repeats (VNTRs): Repetitive DNA sequences

- Short Tandem Repeats (STRs): Shorter repetitive sequences

- Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs): Single base variations

Process of DNA Fingerprinting

[PROCESS: DNA Fingerprinting – Complete Methodology]

1. DNA Extraction:

- Sample collection (blood, saliva, hair, semen)

- Cell lysis and protein removal

- DNA purification and quantification

2. DNA Amplification:

- PCR amplification: Target specific STR loci

- Primers: Flank repetitive sequences

- Multiplex PCR: Amplify multiple loci simultaneously

3. Electrophoresis:

- Gel electrophoresis: Separate fragments by size

- Capillary electrophoresis: Higher resolution separation

- Fluorescent detection: Automated analysis

4. Analysis:

- Allele calling: Determine repeat numbers

- Profile comparison: Match unknown to known samples

- Statistical analysis: Calculate match probability

Applications of DNA Fingerprinting

Forensic Applications:

- Criminal investigations

- Mass disaster victim identification

- Sexual assault cases

- Cold case investigations

Paternity Testing:

- Child-parent relationship determination

- Immigration cases

- Inheritance disputes

Medical Applications:

- Organ transplant matching

- Genetic disorder diagnosis

- Pharmacogenomics

Conservation Biology:

- Species identification

- Population genetics studies

- Wildlife forensics

CODIS System

The Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) uses 13-20 STR loci for forensic identification:

- Core loci: Standard set used globally

- Database search: Compare profiles across jurisdictions

- Quality standards: Ensure reliable results

Historical Context: The innocence Project has used DNA fingerprinting to exonerate over 375 wrongfully convicted individuals, highlighting both the power and importance of accurate genetic analysis.

12. Advanced Topics and Current Research

Epigenetics: Beyond the DNA Sequence

Epigenetics studies heritable changes in gene expression without DNA sequence changes.

Mechanisms:

- DNA methylation: Addition of methyl groups to cytosine

- Histone modifications: Chemical changes to histone proteins

- Non-coding RNAs: microRNAs, long non-coding RNAs

Applications:

- Cancer research and therapy

- Aging and longevity studies

- Environmental health

- Transgenerational inheritance

CRISPR-Cas9: Genome Editing Revolution

The CRISPR-Cas9 system, adapted from bacterial immune systems, allows precise genome editing.

Components:

- Guide RNA: Directs Cas9 to target sequence

- Cas9 protein: Cuts DNA at target site

- Repair template: Provides new sequence for insertion

Applications:

- Gene therapy for genetic diseases

- Agricultural crop improvement

- Basic research tool

- Potential treatment for cancer and HIV

Synthetic Biology

Synthetic biology combines engineering principles with biology to design new biological systems.

Goals:

- Design biological circuits and devices

- Create artificial life forms

- Produce valuable compounds

- Develop biosensors and bioremediation

Current Research: Scientists are developing synthetic bacteria that can produce biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and even capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Practice Problems Section

Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs)

Question 1: Which of the following enzymes is responsible for joining Okazaki fragments during DNA replication?

a) DNA helicase

b) DNA polymerase I

c) DNA ligase

d) Primase

Solution: c) DNA ligase

Explanation: DNA ligase creates phosphodiester bonds between adjacent nucleotides, joining the Okazaki fragments on the lagging strand. DNA helicase unwinds the double helix, DNA polymerase I removes primers and fills gaps, and primase synthesizes RNA primers.

Question 2: In the lac operon, which condition leads to maximum transcription of lac genes?

a) High glucose, no lactose

b) No glucose, no lactose

c) High glucose, high lactose

d) No glucose, high lactose

Solution: d) No glucose, high lactose

Explanation: Maximum transcription requires both the absence of glucose (allowing CAP-cAMP formation for positive control) and the presence of lactose (inactivating the repressor for negative control removal).

Question 3: The genetic code is said to be degenerate because:

a) It contains stop codons

b) Multiple codons code for the same amino acid

c) It is read in triplets

d) It is universal

Solution: b) Multiple codons code for the same amino acid

Explanation: Degeneracy refers to the redundancy in the genetic code where most amino acids are encoded by more than one codon. This provides protection against harmful mutations.

Question 4: Which of the following is NOT a difference between DNA and RNA?

a) DNA contains deoxyribose, RNA contains ribose

b) DNA is double-stranded, RNA is single-stranded

c) DNA contains thymine, RNA contains uracil

d) DNA contains phosphate groups, RNA does not

Solution: d) DNA contains phosphate groups, RNA does not

Explanation: Both DNA and RNA contain phosphate groups as part of their sugar-phosphate backbone. The other options represent actual differences between DNA and RNA.

Question 5: The Meselson-Stahl experiment demonstrated:

a) DNA is the genetic material

b) The genetic code is triplet in nature

c) DNA replication is semi-conservative

d) Proteins are synthesized on ribosomes

Solution: c) DNA replication is semi-conservative

Explanation: The Meselson-Stahl experiment used nitrogen isotopes to show that each new DNA molecule contains one original strand and one newly synthesized strand, proving semi-conservative replication.

Short Answer Questions

Question 6: Explain why the leading and lagging strands are synthesized differently during DNA replication.

Solution:

DNA replication occurs differently on leading and lagging strands due to the antiparallel nature of DNA and the directional constraint of DNA polymerase:

Leading Strand:

- Synthesized continuously in the 5′ to 3′ direction

- DNA polymerase moves in the same direction as the replication fork

- Only one primer needed at the origin

- Smooth, uninterrupted synthesis

Lagging Strand:

- Synthesized discontinuously in short fragments (Okazaki fragments)

- DNA polymerase moves opposite to the replication fork direction

- Multiple primers needed for each fragment

- Fragments must be joined by DNA ligase

This difference arises because DNA polymerase can only add nucleotides to the 3′-OH end of a growing chain, and the two strands of DNA are antiparallel.

Question 7: Describe the role of the three different types of RNA in protein synthesis.

Solution:

mRNA (Messenger RNA):

- Carries genetic information from DNA to ribosomes

- Contains codons that specify amino acid sequence

- Processed in eukaryotes (5′ cap, 3′ poly-A tail, splicing)

- Template for translation

tRNA (Transfer RNA):

- Adapter molecule between mRNA and amino acids

- Contains anticodon complementary to mRNA codon

- Carries specific amino acid attached at 3′ end

- Ensures accuracy of translation through aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases

rRNA (Ribosomal RNA):

- Structural component of ribosomes

- Catalyzes peptide bond formation (ribozyme activity)

- Provides binding sites for mRNA and tRNA

- Most abundant RNA in cells (80% of total RNA)

All three types work together in translation: mRNA provides the template, tRNA brings amino acids, and rRNA catalyzes protein synthesis.

Long Answer Questions

Question 8: Describe the complete process of transcription in eukaryotes, highlighting the differences from prokaryotic transcription.

Solution:

Eukaryotic Transcription Process:

Initiation:

- RNA polymerase II recognizes promoter elements (TATA box, CAAT box, GC box)

- General transcription factors (TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIID, etc.) assemble at promoter

- Formation of pre-initiation complex

- DNA unwinding and transcription bubble formation

- RNA synthesis begins

Elongation:

- RNA polymerase II moves along template strand (3′ to 5′)

- RNA synthesized in 5′ to 3′ direction

- Transcription factors may enhance or inhibit elongation

- Co-transcriptional processing begins

Termination:

- Polyadenylation signal sequence recognized

- Cleavage and polyadenylation factors act

- RNA cleaved downstream of poly-A signal

- RNA polymerase II released

Key Differences from Prokaryotic Transcription:

| Aspect | Prokaryotes | Eukaryotes |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Polymerases | Single enzyme | Three enzymes (I, II, III) |

| Location | Cytoplasm | Nucleus |

| Promoter Recognition | Sigma factors | Transcription factors |

| RNA Processing | None | Extensive (capping, splicing, polyadenylation) |

| Coupling | Transcription-translation coupled | Separate processes |

| mRNA Type | Polycistronic | Monocistronic |

RNA Processing in Eukaryotes:

- 5′ Capping: Addition of 7-methylguanosine cap for stability and translation initiation

- 3′ Polyadenylation: Addition of poly-A tail for mRNA stability and translation efficiency

- Splicing: Removal of introns by spliceosome, alternative splicing creates protein diversity

Case Study Analysis

Question 9: A research laboratory is studying a new antibiotic that inhibits bacterial protein synthesis. Preliminary tests show that the antibiotic binds specifically to the 30S ribosomal subunit and prevents the binding of aminoacyl-tRNA to the A site. Analyze the effect of this antibiotic on bacterial translation and explain why it would be effective against bacterial infections without significantly affecting human cells.

Solution:

Analysis of Antibiotic Effect:

Mechanism of Action:

- Target: 30S ribosomal subunit (specific to prokaryotes)

- Effect: Blocks aminoacyl-tRNA binding to A site

- Result: Translation elongation cannot proceed

Impact on Bacterial Translation:

- Initiation: May proceed normally as fMet-tRNA binds to P site

- Elongation: Completely blocked as no aminoacyl-tRNA can enter A site

- Protein Synthesis: Severely inhibited, leading to bacterial death

- Cellular Processes: All protein-dependent processes affected

Selectivity for Bacterial Cells:

Structural Differences:

- Bacterial ribosomes: 70S (30S + 50S subunits)

- Human ribosomes: 80S (40S + 60S subunits)

- Different rRNA sequences and protein compositions

- Distinct binding sites and conformations

Clinical Effectiveness:

- High specificity reduces side effects on human cells

- Bactericidal action (kills bacteria rather than just inhibiting growth)

- Broad spectrum if effective against multiple bacterial species

- Low resistance development if binding site is highly conserved

Real-World Example: This mechanism is similar to streptomycin, which binds to the 30S subunit and causes misreading of mRNA, leading to defective proteins and bacterial death.

Potential Limitations:

- Resistance development through ribosomal mutations

- Possible effects on mitochondrial ribosomes (70S type)

- Need for adequate tissue penetration

Data Analysis Questions

Question 10: The following table shows the results of DNA fingerprinting analysis using 5 STR loci for a paternity case. Analyze the data and determine the likelihood of paternity.

| STR Locus | Mother | Child | Alleged Father |

|---|---|---|---|

| D3S1358 | 15,17 | 14,17 | 14,16 |

| vWA | 16,18 | 16,17 | 17,19 |

| FGA | 21,24 | 21,22 | 22,25 |

| D8S1179 | 12,13 | 13,15 | 15,16 |

| D21S11 | 29,30 | 28,30 | 28,31 |

Solution:

Analysis Method:

For each locus, determine if the alleged father could contribute an allele present in the child but not in the mother.

Locus-by-Locus Analysis:

D3S1358:

- Child: 14, 17

- Mother: 15, 17 (contributes 17 to child)

- Child’s other allele: 14

- Alleged father: 14, 16 (can contribute 14) ✓

vWA:

- Child: 16, 17

- Mother: 16, 18 (contributes 16 to child)

- Child’s other allele: 17

- Alleged father: 17, 19 (can contribute 17) ✓

FGA:

- Child: 21, 22

- Mother: 21, 24 (contributes 21 to child)

- Child’s other allele: 22

- Alleged father: 22, 25 (can contribute 22) ✓

D8S1179:

- Child: 13, 15

- Mother: 12, 13 (contributes 13 to child)

- Child’s other allele: 15

- Alleged father: 15, 16 (can contribute 15) ✓

D21S11:

- Child: 28, 30

- Mother: 29, 30 (contributes 30 to child)

- Child’s other allele: 28

- Alleged father: 28, 31 (can contribute 28) ✓

Conclusion:

The alleged father cannot be excluded as the biological father. All paternal alleles in the child can be explained by inheritance from the alleged father. However, this does not prove paternity definitively, as other men might share these same alleles.

Statistical Significance:

To calculate the probability of paternity, we would need:

- Population frequencies for each allele

- Combined paternity index (CPI) calculation

- Typically requires >99.9% probability for legal purposes

Exam Preparation Strategies

High-Yield Topics for CBSE Board Exams

Most Frequently Tested Concepts:

- DNA Structure and Replication: Semi-conservative nature, enzymes involved

- Central Dogma: Direction of information flow, exceptions

- Genetic Code: Properties (universality, degeneracy, triplet nature)

- lac Operon: Regulation mechanism, positive and negative control

- Translation Process: Initiation, elongation, termination steps

- DNA Fingerprinting: Principles, applications, VNTR/STR analysis

Problem-Solving Approach

For Molecular Biology Problems:

- Identify the process: Replication, transcription, translation, or regulation

- Determine the organism: Prokaryote vs eukaryote differences

- Consider directionality: 5′ to 3′ for synthesis, antiparallel strands

- Apply base-pairing rules: A-T/U, G-C in DNA/RNA

- Check for special conditions: Presence/absence of inducers, temperature sensitivity

Common Exam Mistakes and Prevention

Mistake 1: Confusing transcription and translation

Prevention: Remember: Transcription = DNA to RNA (nucleus in eukaryotes), Translation = RNA to protein (ribosomes)

Mistake 2: Wrong direction of synthesis

Prevention: All nucleic acid synthesis is 5′ to 3′, proteins are synthesized N-terminal to C-terminal

Mistake 3: Mixing up prokaryotic and eukaryotic features

Prevention: Create comparison tables, focus on key differences

Mistake 4: Forgetting wobble base pairing

Prevention: Remember that tRNA can read multiple codons due to wobble at third position

Memory Aids and Mnemonics

DNA Base Pairing: “Apples in Trees” (A-T), “Grapes in Cars” (G-C)

Genetic Code Properties: “Universal Degenerates Don’t Overlap Continuously”

- Universal, Degenerate, Doesn’t overlap, Continuous (comma-less)

lac Operon States: “LIP” – Lactose Inactivates Protein (repressor)

Central Dogma: “DNA Reads News Papers” (DNA → RNA → Protein)

RNA Processing: “CAP the TAIL and SPLICE the middle”

Conclusion and Future Directions

The molecular basis of inheritance represents one of the most fundamental and rapidly advancing areas of biology. From Watson and Crick’s double helix to CRISPR gene editing, our understanding of how genetic information is stored, transmitted, and expressed has revolutionized medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology.

As you master these concepts, remember that molecular biology is not just about memorizing structures and pathways – it’s about understanding the elegant mechanisms that life has evolved to perpetuate itself. The DNA in your cells carries the same basic structure as that in bacteria, plants, and every other living organism, testament to the unity of all life on Earth.

Current and Future Applications

The principles you’ve learned are actively shaping our world:

Personalized Medicine: Your genetic profile can now predict drug responses and disease susceptibility, leading to treatments tailored specifically for your genome.

Agricultural Revolution: Gene-edited crops with enhanced nutrition, climate resilience, and reduced environmental impact are being developed using CRISPR technology.

Synthetic Biology: Scientists are designing biological circuits that could produce sustainable fuels, capture carbon dioxide, or even grow materials in space.

Gene Therapy: Treatments for inherited diseases, including successful therapies for sickle cell disease and certain cancers, are becoming reality.

Study Recommendations

- Active Practice: Solve problems daily, focusing on applying concepts rather than rote memorization

- Visual Learning: Draw out processes like replication, transcription, and translation

- Connect Concepts: Link molecular processes to inheritance patterns and genetic disorders

- Current Events: Follow scientific news to see how these principles apply to modern discoveries

- Laboratory Experience: If possible, participate in molecular biology experiments to see these processes in action

Final Thoughts

The molecular basis of inheritance is more than just a chapter in your biology textbook – it’s the foundation for understanding how life works at its most fundamental level. As you prepare for your CBSE Board exams, remember that these concepts will continue to be relevant whether you pursue medicine, biotechnology, research, or any field where understanding life’s mechanisms provides insight and innovation.

The journey from Griffith’s transformation experiments to modern gene therapy represents less than a century of scientific progress, yet it has transformed our understanding of life itself. As the next generation of scientists, engineers, and informed citizens, your mastery of these principles will contribute to solving challenges from genetic diseases to sustainable agriculture to the search for life beyond Earth.

Master these concepts not just for your exams, but as tools for understanding and improving the world around you. The molecular basis of inheritance is, quite literally, the blueprint for life – and now you have the knowledge to read and understand that blueprint.

Success Tip: Approach each practice problem as a puzzle to solve rather than a hurdle to overcome. The elegance and logic of molecular biology will become apparent as you work through examples and see how each component fits perfectly into the larger picture of inheritance and gene expression.

Recommended –

1 thought on “CBSE Class 12 Biology Chapter 5: Molecular Basis of Inheritance – Complete Study Guide with Practice Questions”