The Fascinating World of Heredity Around You

Have you ever wondered why you have your mother’s eyes but your father’s nose? Or why some siblings look identical while others appear completely different? Every day, you witness the incredible phenomena – Principles of Inheritance and Variation – from the striking resemblance between a puppy and its parents to the unique fingerprints that make you one-of-a-kind among billions of people.

The science behind these everyday observations lies in the fundamental principles discovered by Gregor Mendel over 150 years ago. When you see a family where some children have attached earlobes while others have free earlobes, you’re observing Mendelian inheritance in action. When you notice that blood type O parents cannot have a type AB child, you’re witnessing the rules of genetics that govern all life on Earth.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll unravel the mysteries of heredity and variation that shape not just human traits, but also determine crop yields in agriculture, guide breeding programs for livestock, and even influence modern gene therapy treatments for genetic disorders. By understanding these principles, you’ll gain insights into everything from why certain diseases run in families to how genetic engineering creates drought-resistant crops.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Analyze Mendelian inheritance patterns and predict offspring traits using Punnett squares

- Distinguish between different types of dominance including incomplete dominance, co-dominance, and multiple alleles

- Explain the genetic basis of blood group inheritance and solve related problems

- Understand pleiotropy and polygenic inheritance with real-world examples

- Apply the chromosome theory of inheritance to explain genetic phenomena

- Describe sex determination mechanisms in humans, birds, and honey bees

- Analyze linkage and crossing over and their evolutionary significance

- Identify patterns of sex-linked inheritance including hemophilia and color blindness

- Recognize Mendelian disorders like thalassemia and their inheritance patterns

- Understand chromosomal disorders including Down’s syndrome, Turner’s syndrome, and Klinefelter’s syndrome

1: Foundation of Genetic Inheritance – Mendel’s Revolutionary Discoveries

The Father of Genetics and His Pea Plant Experiments

Imagine trying to understand inheritance without knowing about DNA, chromosomes, or genes. This was exactly the challenge Gregor Mendel faced in the 1860s when he began his groundbreaking experiments with pea plants in his monastery garden. His choice of pea plants (Pisum sativum) was brilliant because they showed clear-cut traits, could self-fertilize or cross-fertilize, and had relatively short generation times.

BIOLOGY CHECK: Why did Mendel choose pea plants for his experiments? List three advantages that made pea plants ideal for genetic studies.

Mendel’s Three Laws of Inheritance

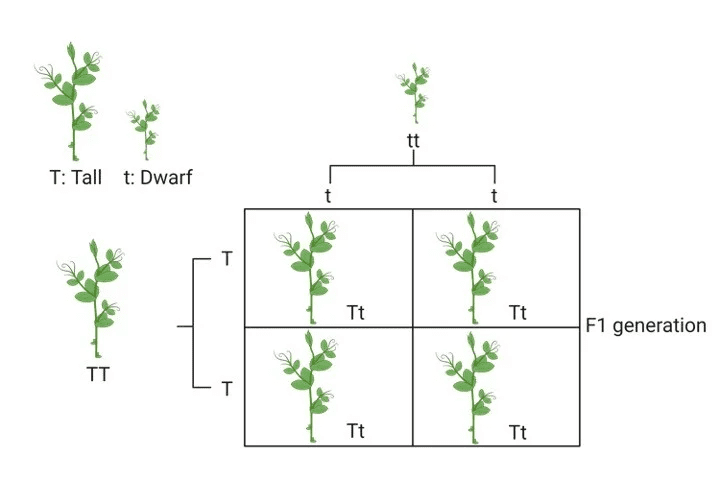

Law of Dominance

When you cross a tall pea plant (TT) with a short pea plant (tt), all offspring in the first generation (F1) are tall (Tt). This demonstrates that some traits are dominant over others. Think of dominance like a louder voice in a conversation – the dominant allele “speaks louder” and masks the expression of the recessive allele.

Law of Segregation

During gamete formation, the two alleles for each trait separate so that each gamete carries only one allele for each trait. It’s like shuffling a deck of cards – each parent contributes one “card” (allele) to determine the offspring’s trait.

Law of Independent Assortment

Different traits are inherited independently of each other, provided they’re on different chromosomes. When Mendel crossed plants differing in two traits (like seed color and seed shape), he found that the inheritance of one trait didn’t influence the inheritance of another.

Modern Understanding of Mendelian Genetics

Today, we know that Mendel’s “factors” are genes located on chromosomes. Each gene exists in different forms called alleles. Your genetic makeup (genotype) determines your observable characteristics (phenotype), though environmental factors also play crucial roles.

[REAL-WORLD BIOLOGY: Mendelian inheritance explains why approximately 25% of children from two brown-eyed parents (Bb × Bb) can have blue eyes (bb), surprising many families who don’t understand basic genetics.]

2: When Mendel’s Rules Don’t Apply – Deviations from Classical Inheritance

Incomplete Dominance: When Traits Blend

Unlike Mendel’s pea plants where one trait completely dominated another, some traits show incomplete dominance. Imagine mixing red and white paint to get pink – that’s essentially what happens with incomplete dominance.

In snapdragons, when you cross red flowers (RR) with white flowers (WW), the F1 generation produces pink flowers (RW). Neither allele is completely dominant, so both contribute to the phenotype. This pattern appears in human hair texture, where straight hair (SS) crossed with curly hair (CC) often produces wavy hair (SC).

PROCESS: Incomplete Dominance Inheritance Pattern – Step-by-step analysis showing how RR × WW → RW (pink), and RW × RW → 1RR:2RW:1WW (1 red:2 pink:1 white)

Co-dominance: When Both Traits Show Up

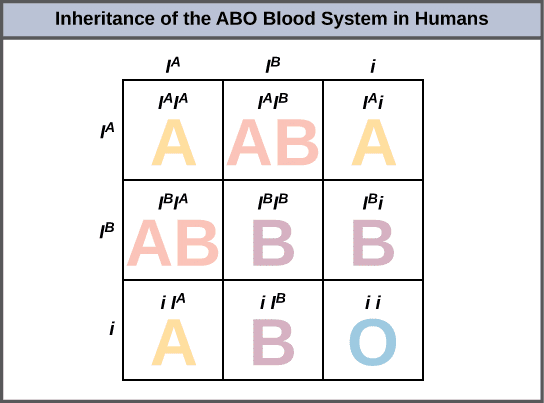

Co-dominance differs from incomplete dominance because both alleles are fully expressed simultaneously. The classic example is the ABO blood group system, where both IA and IB alleles are co-dominant when present together, resulting in AB blood type.

COMMON ERROR ALERT: Students often confuse incomplete dominance with co-dominance. Remember: incomplete dominance creates a blended phenotype (pink flowers), while co-dominance shows both traits distinctly (AB blood type shows both A and B antigens).

Multiple Alleles: More Than Two Options

While each individual can only carry two alleles for any gene, populations can have multiple alleles for the same gene. The ABO blood system demonstrates this perfectly with three alleles: IA, IB, and i.

Blood Group Genetics Explained:

- Type A: IAIA or IAi genotypes

- Type B: IBIB or IBi genotypes

- Type AB: IAIB genotype (co-dominance)

- Type O: ii genotype (recessive)

This system explains why two type A parents can have a type O child (both parents are IAi), but type AB parents cannot have type O children.

3: Complex Inheritance Patterns – Beyond Simple Dominant-Recessive

Pleiotropy: One Gene, Multiple Effects

Pleiotropy occurs when a single gene affects multiple, seemingly unrelated traits. It’s like a master switch that controls several different functions in your body. Phenylketonuria (PKU) provides an excellent example – mutations in the PAH gene not only affect amino acid metabolism but also impact skin pigmentation, hair color, and intellectual development if untreated.

Marfan syndrome demonstrates pleiotropy dramatically, where mutations in the FBN1 gene affect connective tissue throughout the body, causing:

- Tall, thin body structure

- Long fingers and toes (arachnodactyly)

- Heart valve problems

- Eye lens dislocation

- Spinal abnormalities

REAL-WORLD BIOLOGY: Understanding pleiotropy helps doctors recognize genetic syndromes early. When they see a tall, thin teenager with heart problems and eye issues, they might suspect Marfan syndrome and test the FBN1 gene.

Polygenic Inheritance: Many Genes, One Trait

While pleiotropy involves one gene affecting many traits, polygenic inheritance involves many genes affecting one trait. Human height, skin color, and intelligence show polygenic inheritance patterns.

Consider skin color in humans – at least four different genes contribute to melanin production and distribution. Each gene has multiple alleles that add varying amounts of pigment. This creates a continuous variation rather than distinct categories, explaining why human skin color exists on a spectrum rather than in discrete groups.

PROCESS: Polygenic Inheritance Analysis – Using height as an example, show how multiple genes (A, B, C, D) each contribute additively to final phenotype, creating bell curve distribution in populations

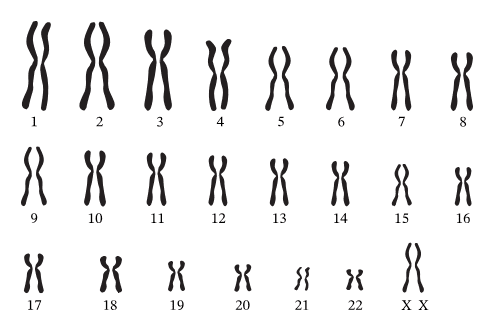

4: The Chromosome Theory of Inheritance – Connecting Genes to Chromosomes

From Mendel’s Factors to Chromosomes

Walter Sutton and Theodor Boveri independently proposed the chromosome theory of inheritance in 1902-1903, connecting Mendel’s abstract “factors” to physical structures in cells. They observed that chromosomes behave exactly like Mendel’s factors during meiosis:

- Chromosomes exist in homologous pairs (like Mendel’s allele pairs)

- Chromosome pairs separate during meiosis (like allele segregation)

- Different chromosome pairs assort independently (like Mendel’s independent assortment)

HISTORICAL CONTEXT: The chromosome theory was initially controversial because scientists couldn’t directly observe genes. It wasn’t until the 1940s that Oswald Avery proved DNA was the genetic material, finally validating this theory.

Gene Mapping and Chromosomal Organization

Modern techniques reveal that human chromosomes contain thousands of genes arranged linearly. Chromosome 1, our largest chromosome, contains over 4,000 genes, while the Y chromosome contains fewer than 200 genes. Understanding gene locations helps predict inheritance patterns and diagnose genetic disorders.

5: Sex Determination – The Genetic Basis of Male and Female

Sex Determination in Humans: The XY System

Human sex determination follows the XY system where females are XX and males are XY. During meiosis, females can only contribute X chromosomes to offspring, while males contribute either X (producing female offspring) or Y (producing male offspring). This creates an approximately 50:50 sex ratio in populations.

The Y chromosome carries the SRY gene (Sex-determining Region Y), which acts as a master switch for male development. Without SRY, the default developmental pathway produces a female, regardless of chromosome composition.

BIOLOGY CHECK: If a man has a Y chromosome abnormality where the SRY gene is deleted, predict the likely sex determination outcome and explain your reasoning.

Sex Determination in Birds: The ZW System

Birds use a different system where males are ZZ and females are ZW. This reverses the mammalian pattern – female birds determine offspring sex by contributing either Z (male offspring) or W (female offspring) chromosomes.

Sex Determination in Honey Bees: Haplodiploidy

Honey bee sex determination uses the most unusual system – haplodiploidy. Females develop from fertilized eggs (diploid), while males develop from unfertilized eggs (haploid). This creates unique genetic relationships where sisters share more genes with each other than with their own offspring.

REAL-WORLD BIOLOGY: Haplodiploidy explains the complex social structure in bee colonies. Worker bees are more closely related to their sisters than to potential offspring, making it evolutionarily advantageous to help raise siblings rather than reproduce themselves.

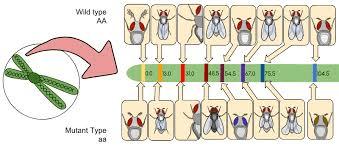

6: Linkage and Crossing Over – When Genes Travel Together

Understanding Genetic Linkage

Independent assortment works perfectly when genes are on different chromosomes, but genes on the same chromosome tend to be inherited together – they’re linked. The closer two genes are on a chromosome, the stronger their linkage and the less likely they are to separate during meiosis.

Think of linked genes like passengers on the same train car – they usually travel together to the same destination. However, sometimes passengers might switch cars during the journey, just as genes can separate through crossing over.

The Process of Crossing Over

During prophase I of meiosis, homologous chromosomes pair up and exchange segments in a process called crossing over or recombination. This process:

- Increases genetic diversity in offspring

- Allows scientists to map gene locations

- Explains why some gene combinations appear more frequently than others

PROCESS: Crossing Over Mechanism – Detailed explanation of synapsis, chiasma formation, and genetic recombination during meiosis I, showing how this creates new allele combinations

Recombination Frequency and Gene Mapping

Scientists use recombination frequency to determine how far apart genes are on chromosomes. The recombination frequency between two genes equals the percentage of offspring showing recombinant (new) combinations of traits. One map unit (centimorgan) equals 1% recombination frequency.

7: Sex-Linked Inheritance – When Gender Determines Genetic Expression

X-Linked Inheritance Patterns

Sex-linked traits are controlled by genes located on sex chromosomes, primarily the X chromosome. Since males have only one X chromosome, they express whatever allele is present, while females need two copies of a recessive allele to express the trait.

Hemophilia: The Royal Disease

Hemophilia A, caused by mutations in the Factor VIII gene on the X chromosome, provides a classic example of X-linked recessive inheritance. Queen Victoria was a carrier, and the trait spread through European royal families, earning it the nickname “the royal disease.”

Inheritance Pattern:

- Affected fathers cannot pass hemophilia to sons (no X chromosome transfer)

- All daughters of affected fathers are carriers

- Carrier mothers have a 50% chance of passing the trait to each child

- Sons who inherit the trait are affected; daughters become carriers

REAL-WORLD BIOLOGY: Modern treatment for hemophilia includes clotting factor concentrates and gene therapy trials. Understanding X-linked inheritance helps genetic counselors advise families about risks and reproductive choices.

Color Blindness: Red-Green Vision Defects

Red-green color blindness affects about 8% of males but only 0.5% of females, demonstrating typical X-linked recessive inheritance. The genes for red and green opsins are located on the X chromosome, and mutations in these genes cause various types of color vision deficiencies.

COMMON ERROR ALERT: Students often think color-blind individuals see no colors. In reality, most color-blind people have difficulty distinguishing specific color combinations, particularly red-green or blue-yellow.

8: Mendelian Disorders in Humans – Single Gene Defects

Thalassemia: A Closer Look at Hemoglobin Disorders

Thalassemia represents one of the most important Mendelian disorders affecting millions worldwide, particularly in Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Southeast Asian populations. This group of inherited blood disorders affects hemoglobin production, the protein that carries oxygen in red blood cells.

Types of Thalassemia:

α-Thalassemia: Results from mutations in α-globin genes on chromosome 16. Since humans normally have four α-globin genes (two on each chromosome 16), the severity depends on how many genes are affected:

- Silent carrier (1 gene affected): No symptoms

- α-thalassemia minor (2 genes affected): Mild anemia

- Hemoglobin H disease (3 genes affected): Moderate to severe anemia

- α-thalassemia major (4 genes affected): Usually fatal in utero

β-Thalassemia: Results from mutations in β-globin genes on chromosome 11. With only two β-globin genes, the effects are more severe:

- β-thalassemia minor: One gene affected, mild anemia

- β-thalassemia major (Cooley’s anemia): Both genes severely affected, requires lifelong blood transfusions

PROCESS: Thalassemia Inheritance Analysis – Show how carrier parents (β-thalassemia minor) have a 25% chance of having a child with β-thalassemia major, using Punnett square analysis

Molecular Basis of Thalassemia

Normal adult hemoglobin (HbA) consists of two α-chains and two β-chains (α2β2). In β-thalassemia, reduced β-chain production creates an imbalance, leading to:

- Excess α-chains that damage red blood cell membranes

- Ineffective erythropoiesis (red blood cell production)

- Chronic anemia and compensatory mechanisms

REAL-WORLD BIOLOGY: Thalassemia carriers have some protection against malaria, explaining why these mutations persist in populations from malaria-endemic regions. This demonstrates how genetic disorders can sometimes confer survival advantages.

9: Chromosomal Disorders – When Chromosome Number or Structure Changes

Down Syndrome: Trisomy 21

Down syndrome, caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21, represents the most common autosomal trisomy compatible with life. This condition demonstrates how gene dosage affects development and provides insights into chromosome function.

Characteristics of Down Syndrome:

- Intellectual disability (usually mild to moderate)

- Distinctive facial features (upward slanting eyes, small nose bridge)

- Increased risk of heart defects, digestive problems, and early-onset Alzheimer’s disease

- Short stature and hypotonia (low muscle tone)

Molecular Mechanisms:

The extra chromosome 21 contains over 300 genes, leading to overexpression of crucial proteins. Key genes include:

- DYRK1A: Affects brain development and cognitive function

- COL6A1: Influences connective tissue development

- SOD1: Involved in oxidative stress response

Maternal Age Effect

Down syndrome risk increases dramatically with maternal age:

- Age 20: Risk 1 in 1,500

- Age 35: Risk 1 in 350

- Age 40: Risk 1 in 100

- Age 45: Risk 1 in 30

This occurs because oocytes arrest in meiosis I for years or decades, increasing the likelihood of nondisjunction (failure of chromosomes to separate properly).

Turner Syndrome: Missing X Chromosome

Turner syndrome (45,X) affects approximately 1 in 2,500 female births and results from complete or partial absence of one X chromosome. This condition illustrates the importance of X chromosome genes in development.

Clinical Features:

- Short stature and webbed neck

- Cardiovascular abnormalities (coarctation of aorta)

- Ovarian dysgenesis leading to infertility

- Normal intelligence but specific learning difficulties

BIOLOGY CHECK: Explain why Turner syndrome affects only females and predict what would happen if a male had only one sex chromosome (45,Y).

Klinefelter Syndrome: Extra X Chromosome

Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) affects approximately 1 in 650 male births and demonstrates the effects of extra X chromosome material in males.

Clinical Features:

- Tall stature with long limbs

- Hypogonadism and infertility

- Gynecomastia (breast enlargement)

- Normal intelligence but potential learning difficulties

Genetic Mechanisms:

Despite X-inactivation, some genes escape inactivation and are overexpressed in XXY males. The pseudoautosomal regions of the X chromosome remain active, contributing to the clinical phenotype.

CURRENT RESEARCH: Scientists are investigating why certain X chromosome genes escape inactivation and how this contributes to the phenotypes seen in sex chromosome disorders. This research may lead to better treatments for affected individuals.

10: Practice Problems Section – Master Genetics Through Application

Problem Set 1: Mendelian Inheritance (Basic Level)

Problem 1: In humans, brown eyes (B) are dominant over blue eyes (b). If both parents have brown eyes but are heterozygous (Bb), what are the expected genotypic and phenotypic ratios in their offspring?

Solution:

Parents: Bb × Bb

Punnett Square:

B b

B BB Bb

b Bb bbGenotypic ratio: 1 BB : 2 Bb : 1 bb

Phenotypic ratio: 3 brown eyes : 1 blue eyes

Probability of blue-eyed child: 25% or 1/4

Problem 2: A man with type A blood (IAIA) marries a woman with type B blood (IBIB). What are the possible blood types of their children?

Solution:

Parents: IAIA × IBIB

All offspring will have genotype IAIB

Blood type of all children: Type AB

Probability: 100% Type AB

Problem Set 2: Complex Inheritance Patterns (Intermediate Level)

Problem 3: In snapdragons, red flowers (RR) and white flowers (WW) show incomplete dominance. If you cross two pink flowers (RW), what will be the phenotypic ratio in the F2 generation?

Solution:

Parents: RW × RW

Punnett Square:

R W

R RR RW

W RW WWPhenotypic ratio: 1 red : 2 pink : 1 white

This 1:2:1 ratio is characteristic of incomplete dominance

Problem 4: A woman with type AB blood marries a man with type O blood. What are the possible blood types and their probabilities for their children?

Solution:

Parents: IAIB × ii

Punnett Square:

IA IB

i IAi IBi

i IAi IBiResults:

- 50% Type A blood (IAi)

- 50% Type B blood (IBi)

- 0% Type AB or Type O blood

Problem Set 3: Sex-Linked Inheritance (Advanced Level)

Problem 5: Hemophilia is an X-linked recessive trait. If a carrier woman (XHXh) marries a normal man (XHY), what are the expected outcomes for their children?

Solution:

Parents: XHXh × XHY

Punnett Square:

XH Xh

XH XHXH XHXh

Y XHY XhYResults:

- Daughters: 50% normal (XHXH), 50% carriers (XHXh)

- Sons: 50% normal (XHY), 50% hemophiliac (XhY)

- Overall: 25% normal daughters, 25% carrier daughters, 25% normal sons, 25% affected sons

Problem 6: Color blindness is X-linked recessive. If a color-blind woman marries a man with normal vision, predict the vision status of their children and grandchildren (assuming the children marry individuals with normal vision).

Solution:

F1 Generation:

Parents: XcXc × XCY

- All daughters: XCXc (carriers with normal vision)

- All sons: XcY (color-blind)

F2 Generation (daughters marry normal men, sons marry normal women):

Daughter crosses: XCXc × XCY

- 25% normal daughters, 25% carrier daughters, 25% normal sons, 25% color-blind sons

Son crosses: XcY × XCXC

- All daughters carriers (normal vision), all sons normal

Problem Set 4: Pedigree Analysis (Expert Level)

Problem 7: [INSERT DIAGRAM: Three-generation pedigree showing autosomal recessive inheritance pattern]

Analyze the given pedigree for an autosomal recessive trait. Determine the genotypes of individuals II-1, II-2, and III-1, and calculate the probability that III-2 is a carrier.

Solution Steps:

- Identify inheritance pattern: Affected individuals appear in same generation with unaffected parents = autosomal recessive

- Assign genotypes: Affected individuals = aa, unaffected = AA or Aa

- Use logic: If unaffected parents have affected children, both parents must be carriers (Aa)

- Calculate probabilities: Use Punnett squares for specific crosses

Problem Set 5: Chromosomal Disorders (Application Level)

Problem 8: A 35-year-old woman is concerned about her risk of having a child with Down syndrome. Explain the genetic basis of this condition, why maternal age affects risk, and what genetic counseling options are available.

Solution:

Genetic Basis:

- Down syndrome = Trisomy 21 (47,+21)

- Caused by nondisjunction during meiosis I or II

- Results in extra chromosome 21 in all or some cells

Maternal Age Effect:

- Oocytes arrest in meiosis I for years/decades

- Cohesin proteins deteriorate over time

- Increased risk of chromosome nondisjunction

- Risk increases exponentially after age 35

Genetic Counseling Options:

- Prenatal screening (maternal serum markers, ultrasound)

- Diagnostic testing (amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling)

- Risk assessment based on maternal age and family history

- Discussion of reproductive options

11: Advanced Applications and Current Research

Gene Therapy and Genetic Engineering

Modern biotechnology applies Mendelian principles to develop treatments for genetic disorders. Gene therapy attempts to correct defective genes by:

Somatic Gene Therapy:

- Introduces functional genes into affected tissues

- Changes are not inherited by offspring

- Examples: Treatment for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), some forms of inherited blindness

Germline Gene Therapy:

- Modifies genes in reproductive cells

- Changes can be inherited by future generations

- Currently controversial and restricted in many countries

CURRENT RESEARCH: CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology allows precise modification of DNA sequences. Scientists are developing treatments for sickle cell disease, β-thalassemia, and other genetic disorders using this revolutionary tool.

Pharmacogenetics: Personalized Medicine

Understanding individual genetic variations helps predict drug responses and optimize treatments. For example:

- CYP2D6 gene variants affect how people metabolize many medications

- BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations influence breast cancer treatment decisions

- HLA typing prevents adverse drug reactions in certain populations

Agricultural Applications

Mendelian genetics revolutionized agriculture through:

- Hybrid vigor: Crossing inbred lines produces offspring with superior traits

- Marker-assisted selection: Using DNA markers to identify desired genes

- Transgenic crops: Introducing genes from other species for pest resistance or improved nutrition

REAL-WORLD BIOLOGY: Golden Rice contains genes from daffodils and bacteria that produce β-carotene (vitamin A precursor). This genetically modified crop could prevent vitamin A deficiency in developing countries where rice is a staple food.

12: Exam Preparation Strategies and Common Pitfalls

High-Yield Topics for CBSE Board Exams

Most Frequently Tested Concepts:

- Punnett square analysis – Practice with monohybrid, dihybrid, and sex-linked crosses

- Blood group genetics – Focus on ABO system and Rh factor inheritance

- Sex-linked inheritance – Emphasize hemophilia and color blindness patterns

- Chromosomal disorders – Know key features of Down, Turner, and Klinefelter syndromes

- Pedigree analysis – Master identification of inheritance patterns

Problem-Solving Strategies

Step-by-Step Approach:

- Read carefully: Identify what type of inheritance pattern is described

- Define symbols: Clearly define alleles and genotypes before starting

- Set up crosses: Use proper notation (P, F1, F2 generations)

- Show work: Draw Punnett squares and show all calculations

- Check answers: Verify that ratios make biological sense

COMMON ERROR ALERT: Many students confuse phenotypic and genotypic ratios. Remember: genotypic ratios describe genetic makeup (AA, Aa, aa), while phenotypic ratios describe observable traits (brown eyes, blue eyes).

Time Management Tips

During Exams:

- Allocate time wisely: Spend more time on complex pedigree analysis

- Show all work: Partial credit is often awarded for correct methodology

- Double-check calculations: Simple arithmetic errors can cost valuable points

- Use standard notation: Stick to conventional genetic symbols and terminology

Memory Aids and Mnemonics

For Blood Groups:

“I Am Always Brave But sometimes in trouble” (IA, IB, i alleles)

For Sex-Linked Inheritance:

“X-linked traits: X-tra care needed for males” (males more affected due to single X chromosome)

For Chromosomal Disorders:

“Down = Different face, Developmental delays” (Down syndrome characteristics)

“Turner = Tall parents, Tiny daughter” (Turner syndrome growth issues)

Conclusion and Future Study Directions

Mastering the Fundamentals

The principles of inheritance and variation form the cornerstone of modern biology, medicine, and biotechnology. By understanding these concepts, you’ve gained insights into:

- How traits pass from parents to offspring through predictable patterns

- Why genetic diversity is essential for species survival

- How genetic disorders arise and can be diagnosed or treated

- The molecular basis of inheritance from DNA to chromosomes to organisms

Connecting to Other Biology Units

Integration with Other Chapters:

- Molecular Biology: DNA structure and replication provide the molecular foundation for inheritance

- Evolution: Genetic variation drives natural selection and evolutionary change

- Biotechnology: Understanding inheritance enables genetic engineering and gene therapy

- Human Health: Genetic principles guide disease diagnosis, treatment, and prevention

Career Applications

Understanding genetics opens doors to exciting career paths:

- Genetic Counselor: Help families understand inherited conditions

- Medical Geneticist: Diagnose and treat genetic disorders

- Plant Breeder: Develop improved crop varieties using genetic principles

- Biotechnology Researcher: Create new therapies using genetic engineering

- Forensic Scientist: Use DNA analysis to solve crimes and identify remains

Preparing for Advanced Studies

For Medical Entrance Exams:

- Master pedigree analysis and probability calculations

- Understand genetic basis of common diseases

- Know current applications in medicine and biotechnology

- Practice time management with complex genetic problems

For Further Biology Studies:

- Population genetics and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- Quantitative genetics and statistical analysis

- Molecular genetics and gene regulation

- Genomics and bioinformatics applications

Final Study Recommendations

Effective Study Strategies:

- Practice regularly: Work through genetic problems daily rather than cramming

- Use visual aids: Draw pedigrees, chromosomes, and inheritance patterns

- Form study groups: Explain concepts to classmates to reinforce learning

- Connect to real life: Look for examples of inheritance in your family and environment

- Stay current: Follow genetic research news to see principles in action

BIOLOGY CHECK: Before your exam, can you explain why understanding inheritance patterns might help doctors recommend preventive treatments for families with genetic disease histories?

The journey through genetics reveals the elegant simplicity underlying life’s incredible complexity. From Mendel’s pea plants to modern gene therapy, the principles you’ve learned continue to drive scientific breakthroughs that improve human health and agricultural productivity. As you prepare for your exams and future studies, remember that genetics isn’t just about memorizing patterns – it’s about understanding the fundamental mechanisms that make life possible and diverse.

Whether you’re calculating the probability of inherited traits, analyzing disease patterns in families, or exploring careers in biotechnology, the solid foundation in genetics you’ve built through this chapter will serve you well. The principles of inheritance and variation connect us to all life on Earth and provide the tools to improve health, agriculture, and our understanding of life itself.

References and Further Reading:

- NCERT Class 12 Biology Textbook, Chapter 5: Principles of Inheritance and Variation

- Klug, W.S., Cummings, M.R., Spencer, C.A. & Palladino, M.A. Concepts of Genetics

- Hartwell, L.H., Hood, L., Goldberg, M.L., Reynolds, A.E. & Silver, L.M. Genetics: From Genes to Genomes

- Current research articles from Nature Genetics, American Journal of Human Genetics, and similar journals

Recommended –

1 thought on “CBSE Class 12 Biology: Complete Guide to Principles of Inheritance and Variation – Master Genetics & Ace Your Exams”