The Physics Behind Everyday Phenomena

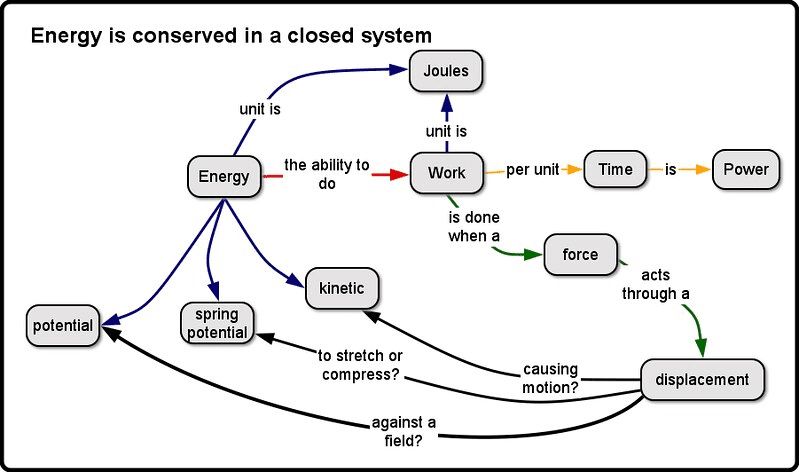

Have you ever wondered why a race car needs such powerful engines, or how a roller coaster can complete an entire loop without falling? The answer lies in understanding work, energy and power – three of the most fundamental and interconnected concepts in all of physics. These principles govern everything from the smartphone in your pocket to the satellites orbiting Earth.

When you walk up a flight of stairs, you’re doing work against gravity, converting chemical energy from your muscles into gravitational potential energy. When you slam on your car’s brakes, kinetic energy transforms into thermal energy through friction. When a wind turbine generates electricity, it converts the kinetic energy of moving air into electrical energy. These energy transformations are happening constantly around us, and mastering their underlying physics is crucial for success in AP Physics C: Mechanics.

This unit builds directly on your understanding of forces and motion from Units 1 and 2, while setting the foundation for rotational motion concepts you’ll encounter later. Unlike AP Physics 1, where energy is often treated conceptually, AP Physics C requires you to master the calculus-based mathematical framework that describes these phenomena with precision.

Learning Objectives: What You’ll Master

By the end of this unit, you will be able to:

Essential Knowledge 3.A: Calculate work done by constant and variable forces using both algebraic and calculus-based methods

Essential Knowledge 3.B: Apply the work-energy theorem to analyze motion in one and multiple dimensions

Essential Knowledge 3.C: Distinguish between conservative and non-conservative forces and their relationship to potential energy

Essential Knowledge 3.D: Apply conservation of mechanical energy to solve complex motion problems

Essential Knowledge 3.E: Calculate gravitational and elastic potential energy in various configurations

Essential Knowledge 3.F: Define and calculate instantaneous power and average power in mechanical systems

Essential Knowledge 3.G: Analyze energy transformations in real-world systems including energy losses

1: Understanding Work – More Than Just Effort

Work in physics has a very specific meaning that often differs from our everyday use of the term. You might say you “worked hard” studying for this exam, but in physics terms, no work was done because there was no displacement! This distinction is crucial for mastering this unit.

PHYSICS CHECK: A student holds a heavy textbook motionless above their head for 10 minutes. How much work do they do on the book? The answer is zero – despite the effort involved, there’s no displacement, so W = 0.

Defining Work Mathematically

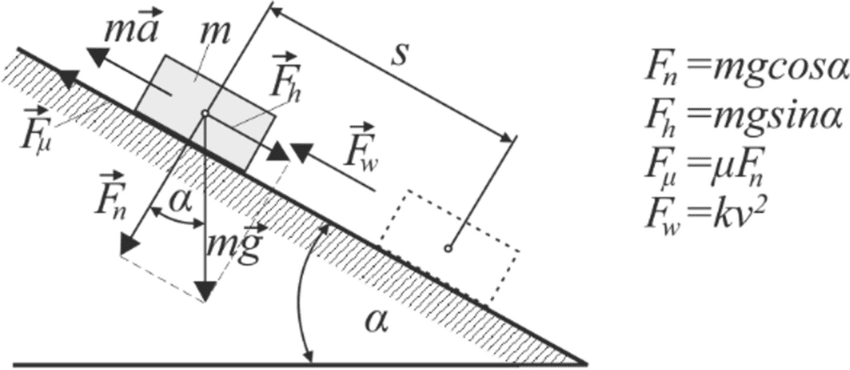

Work is defined as the product of force and displacement in the direction of that force. For constant forces:

[EQUATION: W = F⃗ · d⃗ = Fd cos θ]

Where:

- W = work done (measured in Joules, J)

- F = magnitude of applied force (Newtons, N)

- d = magnitude of displacement (meters, m)

- θ = angle between force and displacement vectors

This dot product formulation reveals why work can be positive, negative, or zero depending on the angle θ:

- θ = 0°: cos(0°) = 1, maximum positive work

- θ = 90°: cos(90°) = 0, no work done

- θ = 180°: cos(180°) = -1, maximum negative work

Real-World Physics: When you push a shopping cart through a store, you do positive work in the direction of motion. The friction force between the wheels and floor does negative work, opposing the motion. Gravity does zero work because it acts perpendicular to the horizontal displacement.

Work Done by Variable Forces

When forces change with position, we must use calculus to calculate work:

[EQUATION: W = ∫F⃗ · dr⃗ = ∫F(x)dx from x₁ to x₂]

This integral represents the area under a Force vs. Position graph – a concept that appears frequently on AP exams.

Problem-Solving Strategy – Work Calculations:

- Identify all forces acting on the object

- Determine the displacement vector

- Calculate the angle between each force and displacement

- Apply W = Fd cos θ for each force

- Sum all work contributions (remembering signs!)

Common Error Alert: Students often forget that work depends on the displacement of the object, not the distance traveled by the force. If you pull a box with a rope over a pulley, the work you do depends on how far YOU move the rope, not how far the box moves.

2: The Work-Energy Theorem – A Powerful Problem-Solving Tool

The work-energy theorem provides one of the most elegant and useful relationships in all of mechanics. It states that the net work done on an object equals its change in kinetic energy:

[EQUATION: Wₙₑₜ = ΔKE = ½mv² – ½mv₀²]

This theorem emerges naturally from Newton’s second law when integrated over displacement, demonstrating the deep connections between different areas of physics.

Derivation of the Work-Energy Theorem:

Starting with Newton’s second law: F = ma = m(dv/dt)

Using the chain rule: dv/dt = (dv/dx)(dx/dt) = v(dv/dx)

Therefore: F = mv(dv/dx)

Integrating over displacement from x₁ to x₂:

∫F dx = ∫mv dv = ½mv² – ½mv₀²

Since ∫F dx = W (work done), we get: W = ΔKE

Why This Theorem Matters

The work-energy theorem allows you to solve motion problems without knowing the details of acceleration or time. This makes it incredibly powerful for analyzing complex systems where forces might vary with position.

Real-World Physics: Race car designers use the work-energy theorem to calculate stopping distances. The kinetic energy of the car must be dissipated as work done against friction and air resistance. Doubling the speed quadruples the kinetic energy, which is why high-speed crashes are so devastating.

Worked Example – Variable Force Analysis:

A 2.0 kg object starts from rest and is acted upon by a force F(x) = 3x² N over a distance of 4.0 m. Find the final velocity.

Given: m = 2.0 kg, v₀ = 0, F(x) = 3x², x = 0 to 4.0 m

Step 1: Calculate work done by variable force

W = ∫₀⁴ 3x² dx = [x³]₀⁴ = 64 J

Step 2: Apply work-energy theorem

Wₙₑₜ = ΔKE = ½mv² – 0

64 = ½(2.0)v²

v = 8.0 m/s

PHYSICS CHECK: Notice how we bypassed the need to find acceleration as a function of position or time. The work-energy theorem provided a direct path to the answer.

3: Conservative Forces and Potential Energy

Understanding the distinction between conservative and non-conservative forces is crucial for energy analysis. This concept determines whether mechanical energy is conserved in a system.

Conservative Forces: Path Independence

A conservative force has a unique property: the work done by the force depends only on the initial and final positions, not on the path taken. Mathematically, this means:

[EQUATION: ∮F⃗ · dr⃗ = 0 for any closed path]

The three most important conservative forces in AP Physics C are:

- Gravitational force: F = mg (near Earth’s surface)

- Elastic force: F = -kx (Hooke’s law)

- Universal gravitational force: F = GMm/r² (for large distances)

Potential Energy: Stored Work Capacity

For conservative forces, we can define potential energy functions that represent stored work capacity:

[EQUATION: U(r) = -∫F⃗ · dr⃗ from reference to position r]

Or equivalently: F⃗ = -∇U = -dU/dx (in one dimension)

Gravitational Potential Energy:

Near Earth’s surface (constant g):

[EQUATION: U_g = mgh]

For universal gravitation:

[EQUATION: U_g = -GMm/r]

The negative sign reflects our choice of zero potential energy at infinite separation.

Elastic Potential Energy:

For springs obeying Hooke’s law:

[EQUATION: U_s = ½kx²]

Where k is the spring constant and x is displacement from equilibrium.

Problem-Solving Strategy – Potential Energy:

- Identify conservative forces in the system

- Choose appropriate reference points for zero potential energy

- Calculate potential energy at initial and final positions

- Remember that only changes in potential energy have physical meaning

Non-Conservative Forces: Energy Dissipation

Non-conservative forces, like friction and air resistance, dissipate mechanical energy. Work done against these forces typically converts organized kinetic or potential energy into random thermal energy.

Common Error Alert: Students often confuse the sign conventions for potential energy and work. Remember: when an object moves in the direction that a conservative force would naturally accelerate it, the potential energy decreases and becomes kinetic energy.

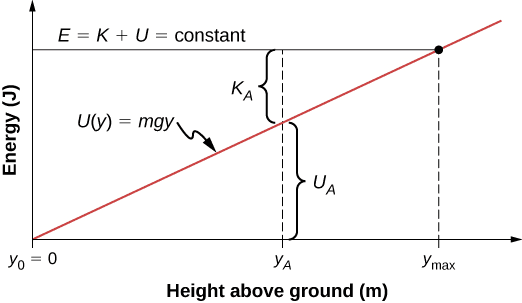

4: Conservation of Mechanical Energy – The Ultimate Problem-Solving Tool

When only conservative forces act on a system, mechanical energy is conserved. This principle provides the most powerful method for solving many physics problems.

The Conservation Equation:

[EQUATION: E_initial = E_final]

[EQUATION: KE_i + U_i = KE_f + U_f]

[EQUATION: ½mv_i² + U_i = ½mv_f² + U_f]

When Energy is NOT Conserved

If non-conservative forces do work, mechanical energy changes:

[EQUATION: ΔE_mechanical = W_non-conservative]

This work typically represents energy “lost” to heat, sound, or other forms.

Real-World Physics: Roller coaster designers use energy conservation to ensure cars have enough speed to complete the track. The highest point determines the minimum initial height needed. Real coasters must start even higher to account for energy losses to friction and air resistance.

Multi-Step Problem Solving with Energy Conservation

Let’s analyze a classic AP Physics problem involving multiple energy transformations:

Worked Example – Pendulum with Spring:

A 0.50 kg mass is attached to a string of length 1.2 m and released from rest at 60° from vertical. At the bottom of its swing, it collides elastically with a horizontal spring (k = 200 N/m). Find the maximum compression of the spring.

Step 1: Pendulum swing (gravity only – conservative)

Choose reference level at bottom of swing

Initial: KE₀ = 0, U₀ = mgh = mg(L – L cos 60°) = mgL(1 – cos 60°)

Final: KE₁ = ½mv₁², U₁ = 0

Energy conservation: mgL(1 – cos 60°) = ½mv₁²

v₁ = √[2gL(1 – cos 60°)] = √[2(9.8)(1.2)(1 – 0.5)] = 3.43 m/s

Step 2: Spring compression (elastic only – conservative)

Initial: KE₁ = ½mv₁², U_spring = 0

Final: KE₂ = 0, U_spring = ½kx²

Energy conservation: ½mv₁² = ½kx²

x = v₁√(m/k) = 3.43√(0.50/200) = 0.17 m

PHYSICS CHECK: Notice how we treated this as two separate conservation problems, using the velocity from the first part as initial conditions for the second part.

Problem-Solving Strategy – Energy Conservation:

- Identify the system and all forces acting

- Determine if mechanical energy is conserved

- Choose convenient reference points for potential energy

- Write energy conservation equation between initial and final states

- Solve for the unknown quantity

- Check units and reasonableness of answer

5: Advanced Energy Applications – Beyond Simple Systems

Real-world systems often involve multiple objects, changing forces, and complex geometries. Mastering these advanced applications is crucial for AP Physics C success.

Systems of Particles

For systems involving multiple objects, we must consider the total mechanical energy:

[EQUATION: E_total = Σ(KE_i + U_i) for all particles]

Internal forces between particles are often conservative (like gravity or springs), while external forces may or may not be conservative.

Energy in Circular Motion

Combining energy conservation with circular motion concepts creates powerful problem-solving opportunities:

Worked Example – Loop-the-Loop:

A ball slides down a frictionless track and enters a vertical circular loop of radius R. What minimum height h must it start from to maintain contact with the track at the top of the loop?

Analysis: At the top of the loop, the minimum condition is when the normal force becomes zero, so gravity alone provides centripetal force:

mg = mv²/R → v_top = √(gR)

Using energy conservation from starting height h to top of loop:

mgh = ½mv_top² + mg(2R)

mgh = ½m(gR) + 2mgR

h = ½R + 2R = 2.5R

Real-World Physics: This calculation explains why water doesn’t fall out of a bucket when swung in a vertical circle at sufficient speed – the same physics governs roller coaster loops and even the orbital motion of satellites.

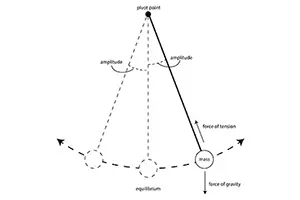

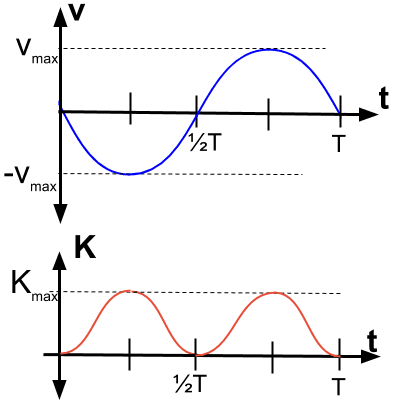

Energy Methods in Oscillatory Motion

Energy conservation provides elegant solutions to oscillation problems:

For simple harmonic motion: E = ½kA² = ½mv² + ½kx²

Where A is amplitude, v is velocity at position x.

Gravitational Potential Energy at Large Distances

For satellites and space missions, we must use the complete gravitational potential energy expression:

[EQUATION: U = -GMm/r]

This leads to important concepts like escape velocity:

[EQUATION: v_escape = √(2GM/R)]

Historical Context: These energy methods were crucial in planning the Apollo missions. NASA engineers used conservation of energy to calculate the minimum velocities needed to reach the Moon and return safely to Earth.

6: Power – The Rate of Energy Transfer

Power quantifies how quickly work is done or energy is transferred. Understanding power is essential for analyzing real-world systems where time matters.

Defining Power

Average power: [EQUATION: P_avg = W/Δt = ΔE/Δt]

Instantaneous power: [EQUATION: P = dW/dt = F⃗ · v⃗]

For constant force and velocity: [EQUATION: P = Fv cos θ]

The SI unit of power is the Watt (W), where 1 W = 1 J/s.

Power in Mechanical Systems

The relationship P = F⃗ · v⃗ reveals why race cars need more power at higher speeds. Even if the driving force remains constant, power requirements increase linearly with velocity.

Real-World Physics: Car engines are rated by horsepower (1 hp = 746 W), but the actual power delivered to the wheels varies with speed and driving conditions. At highway speeds, most power goes to overcoming air resistance, which increases as v³.

Worked Example – Power Analysis:

A 1500 kg car accelerates from 0 to 30 m/s in 8.0 seconds against a constant friction force of 400 N. Calculate:

a) The average power delivered by the engine

b) The instantaneous power at v = 20 m/s

Part a: Average Power

First, find the driving force using kinematics and Newton’s second law:

v = v₀ + at → 30 = 0 + a(8.0) → a = 3.75 m/s²

Net force: F_net = ma = 1500(3.75) = 5625 N

Driving force: F_drive = F_net + f = 5625 + 400 = 6025 N

Distance traveled: x = ½at² = ½(3.75)(8.0)² = 120 m

Work done by engine: W = F_drive × x = 6025 × 120 = 723,000 J

Average power: P_avg = W/t = 723,000/8.0 = 90,400 W = 90.4 kW

Part b: Instantaneous Power

At v = 20 m/s, assuming constant driving force:

P = F_drive × v = 6025 × 20 = 120,500 W = 121 kW

PHYSICS CHECK: Notice how instantaneous power exceeds average power at higher velocities – this is typical for constant-force acceleration.

Efficiency and Power Losses

Real systems always have efficiency less than 100% due to energy losses:

[EQUATION: Efficiency = (Useful power output)/(Total power input) × 100%]

Problem-Solving Strategy – Power Problems:

- Identify whether you need average or instantaneous power

- For average power, calculate total work and time

- For instantaneous power, use P = F⃗ · v⃗

- Consider efficiency losses in real systems

- Pay attention to units (Watts, horsepower, etc.)

7: Laboratory Investigations and Experimental Design

Understanding the experimental foundations of work, energy, and power concepts is crucial for AP Physics C success. The College Board emphasizes hands-on investigation skills that connect theory to real-world measurements.

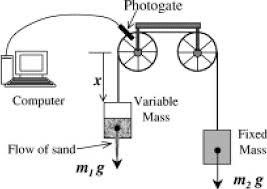

Investigation 1: Determining Spring Constants Through Energy Methods

Experimental Setup: Use a mass-spring system to verify the relationship between elastic potential energy and spring compression.

Procedure:

- Measure spring compression x for various attached masses

- Release masses and measure maximum velocity using photogates

- Apply energy conservation: ½kx² = ½mv²

- Calculate spring constant: k = mv²/x²

Data Analysis Techniques:

- Plot v² vs. x² to verify linear relationship

- Use slope to determine spring constant

- Compare with static method (k = mg/x)

- Analyze sources of experimental uncertainty

Investigation 2: Measuring Gravitational Potential Energy

Experimental Design Challenge: Design an experiment to verify the relationship U = mgh using a pendulum system.

Key Variables to Control:

- String length and mass

- Release angle

- Air resistance effects

- Measurement precision

Error Analysis Considerations:

- Systematic errors from air resistance

- Random errors in angle and timing measurements

- Propagation of uncertainty through calculations

Investigation 3: Power Measurements in Mechanical Systems

Objective: Measure power output of a human climbing stairs and compare to theoretical calculations.

Experimental Method:

- Measure student mass, stair height, and climbing time

- Calculate gravitational power: P = mgh/t

- Use force sensors to measure actual forces during climbing

- Account for efficiency losses in human muscle systems

Real-World Connections: This investigation connects to biomechanics, sports science, and engineering applications where human power output matters.

Common Laboratory Mistakes and Prevention:

- Forgetting to account for systematic measurement errors

- Inadequate data collection for statistical analysis

- Misunderstanding the relationship between precision and accuracy

- Not considering the limitations of idealized theoretical models

8: Problem-Solving Strategies and Common Misconceptions

Mastering Unit 3 requires developing systematic approaches to complex problems while avoiding common conceptual pitfalls.

The RICE Method for Energy Problems:

Recognize the type of problem (work-energy theorem vs. conservation)

Identify all forces and energy forms involved

Choose appropriate reference points and coordinate systems

Execute mathematical solution with proper units

Conceptual Framework for Problem Selection:

Use work-energy theorem when:

- Net work on object is easily calculated

- You need to find final velocity or displacement

- Forces vary with position

Use energy conservation when:

- Only conservative forces do work

- Initial and final states are clearly defined

- Complex force analysis would be difficult

Use power analysis when:

- Time is a crucial factor

- You need to analyze rates of energy transfer

- Efficiency considerations are important

Common Misconceptions and Corrections:

Misconception 1: “Work and energy are the same thing.”

Correction: Work is a process (energy transfer), while energy is a state function. Work changes the energy of a system.

Misconception 2: “Potential energy is always positive.”

Correction: Potential energy can be negative depending on the choice of reference point. Only changes in potential energy have physical significance.

Misconception 3: “Power equals force times velocity always.”

Correction: P = Fv cos θ only when force and velocity are constant. In general, P = F⃗ · v⃗.

Misconception 4: “Energy is always conserved.”

Correction: Only when non-conservative forces do no work is mechanical energy conserved. Total energy (including thermal) is always conserved.

Advanced Problem-Solving Techniques:

Multi-Stage Problems:

Break complex scenarios into sequential stages where different principles apply to each stage.

System Analysis:

Carefully define your system boundaries – what’s included determines which forces are internal vs. external.

Reference Frame Considerations:

Energy and work calculations can depend on reference frame choice, especially in problems involving multiple moving objects.

9: Connections to Other AP Physics Units

Unit 3 concepts provide essential foundations for understanding more advanced physics topics you’ll encounter later in the course.

Connection to Rotational Motion (Units 5-7):

Rotational kinetic energy: KE_rot = ½Iω²

Work done by torque: W = ∫τ dθ

Conservation of angular momentum combines with energy methods

Connection to Oscillations (Unit 8):

Simple harmonic motion emerges from energy considerations

Phase relationships between kinetic and potential energy

Damped oscillations involve non-conservative forces

Connection to Gravitation (Unit 9):

Orbital mechanics requires universal gravitational potential energy

Escape velocity derivation using energy conservation

Kepler’s laws connect to gravitational energy concepts

Real-World Engineering Applications:

Renewable Energy Systems:

Wind turbines convert kinetic energy of air to electrical energy

Hydroelectric systems use gravitational potential energy

Solar panels convert electromagnetic energy to electrical energy

Transportation Technology:

Hybrid vehicles use regenerative braking to recover kinetic energy

Flywheel energy storage systems in race cars

Magnetic levitation trains minimize energy losses through friction

Space Technology:

Gravitational slingshot maneuvers use conservation principles

Satellite orbital mechanics depend on energy balance

Ion propulsion systems optimize power-to-thrust ratios

Historical Context – Energy Concepts:

The development of energy conservation principles in the 19th century revolutionized physics and engineering. Key contributors included:

- James Joule: Mechanical equivalent of heat

- Hermann von Helmholtz: Conservation of energy principle

- William Thomson (Lord Kelvin): Thermodynamic foundations

- Emmy Noether: Mathematical foundations connecting symmetry to conservation laws

These advances enabled the Industrial Revolution and continue to drive modern technological development.

10: Advanced Mathematical Techniques

AP Physics C requires fluency with calculus-based methods for analyzing work, energy, and power in complex systems.

Calculus Applications in Work Calculations:

For position-dependent forces: W = ∫F(x)dx

For time-dependent forces: W = ∫F(t)v(t)dt

For conservative forces: F = -dU/dx

Vector Calculus Concepts:

Work as a line integral: W = ∫F⃗ · dr⃗

Potential energy and conservative fields

Gradient relationships in multiple dimensions

Differential Equations in Energy Systems:

Newton’s second law with energy methods:

F(x) = ma = m(dv/dt) = mv(dv/dx)

This leads to separable differential equations:

∫F(x)dx = ∫mv dv

Power Series and Approximations:

For small oscillations: cos θ ≈ 1 – θ²/2

For relativistic effects: KE ≈ mc²[(1 + v²/2c²) – 1] ≈ ½mv² + 3mv⁴/8c²

Worked Example – Advanced Calculus Application:

A particle moves under the influence of a force F(x) = -kx³ where k = 2.0 N/m³. If the particle starts from rest at x = 3.0 m, find its velocity when it reaches x = 1.0 m.

Solution using work-energy theorem:

W = ∫F(x)dx = ∫₃¹(-kx³)dx = -k[x⁴/4]₃¹ = -k/4(1⁴ – 3⁴) = -k/4(1 – 81) = 20k

W = ΔKE = ½mv² – 0

20k = ½mv²

v = √(40k/m) = √(40×2.0/m) = √(80/m)

Numerical Methods:

When analytical solutions aren’t possible, use numerical integration:

- Trapezoidal rule for work calculations

- Euler’s method for differential equations

- Computational modeling for complex systems

Practice Problems Section

Multiple Choice Questions (AP Style)

1. A 2.0 kg object moves along the x-axis under the influence of a variable force F(x) = 3x² N. If the object’s velocity is 4.0 m/s at x = 2.0 m, what is its velocity at x = 4.0 m?

(A) 6.9 m/s (B) 8.0 m/s (C) 10.0 m/s (D) 12.0 m/s (E) 14.0 m/s

Solution:

Use work-energy theorem: W = ΔKE

W = ∫₂⁴ 3x² dx = [x³]₂⁴ = 64 – 8 = 56 J

½mv₂² – ½mv₁² = W

½(2.0)v₂² – ½(2.0)(4.0)² = 56

v₂² = 16 + 56 = 72

v₂ = 8.5 m/s ≈ 8.0 m/s

Answer: (B)

2. A mass m slides down a frictionless incline of height h and then compresses a spring with spring constant k. The maximum compression of the spring is:

(A) √(2mgh/k) (B) √(mgh/k) (C) √(gh/k) (D) √(2gh/k) (E) 2√(mgh/k)

Solution:

Energy conservation from top of incline to maximum compression:

Initial: KE = 0, U_gravity = mgh, U_spring = 0

Final: KE = 0, U_gravity = 0, U_spring = ½kx²

mgh = ½kx²

x = √(2mgh/k)

Answer: (A)

Free Response Questions

Problem 1 (12 points): Bungee Jump Analysis

A bungee jumper of mass 70 kg jumps from a bridge 50 m above a river. The bungee cord has a natural length of 25 m and spring constant k = 200 N/m.

(a) Calculate the speed of the jumper just before the bungee cord begins to stretch. (3 points)

Solution:

Energy conservation from bridge to end of natural cord length:

Initial: KE = 0, U = mg(50)

Final: KE = ½mv², U = mg(25)

mg(50) = ½mv² + mg(25)

mg(25) = ½mv²

v = √(2g×25) = √(490) = 22.1 m/s

(b) Find the maximum extension of the bungee cord beyond its natural length. (4 points)

Solution:

Energy conservation from bridge to maximum extension:

Initial: KE = 0, U_gravity = mg(50), U_spring = 0

Final: KE = 0, U_gravity = mg(50-25-x), U_spring = ½kx²

mg(50) = mg(25-x) + ½kx²

mg(25+x) = ½kx²

70×9.8×(25+x) = ½×200×x²

17150 + 686x = 100x²

100x² – 686x – 17150 = 0

Using quadratic formula: x = 15.8 m

(c) Calculate the maximum acceleration experienced by the jumper. (3 points)

Solution:

At maximum extension, net force = spring force – weight:

F_net = kx – mg = 200(15.8) – 70(9.8) = 2474 N upward

a_max = F_net/m = 2474/70 = 35.3 m/s² upward

(d) Discuss energy transformations throughout the jump. (2 points)

Solution:

Gravitational potential energy → kinetic energy → elastic potential energy → kinetic energy → gravitational potential energy. Some energy may be lost to air resistance and internal friction in the cord.

Problem 2 (10 points): Variable Force and Power Analysis

A 1.5 kg particle moves along the x-axis under a force F(x) = 4x – 2x² (in Newtons) where x is in meters.

(a) Calculate the work done by this force as the particle moves from x = 0 to x = 3 m. (4 points)

Solution:

W = ∫₀³ F(x)dx = ∫₀³ (4x – 2x²)dx

W = [2x² – (2x³/3)]₀³ = 18 – 18 = 0 J

(b) If the particle starts from rest at x = 0, find its speed at x = 1 m and x = 2 m. (4 points)

Solution:

At x = 1 m:

W = ∫₀¹ (4x – 2x²)dx = [2x² – (2x³/3)]₀¹ = 2 – 2/3 = 4/3 J

½mv² = 4/3

v = √(8/3×1.5) = 1.63 m/s

At x = 2 m:

W = ∫₀² (4x – 2x²)dx = [2x² – (2x³/3)]₀² = 8 – 16/3 = 8/3 J

½mv² = 8/3

v = √(16/3×1.5) = 2.31 m/s

(c) At what position does the particle have maximum kinetic energy? (2 points)

Solution:

Maximum KE occurs where F = 0 (turning point):

4x – 2x² = 0

x(4 – 2x) = 0

x = 0 or x = 2 m

Since the particle starts from rest at x = 0, maximum KE occurs at x = 2 m.

Additional Practice Problems:

3. A roller coaster car of mass 500 kg starts from rest at height 40 m. If 25% of its initial potential energy is lost to friction, what is its speed at the bottom of the track?

4. A 1200 W motor lifts a 200 kg load at constant velocity. What is the maximum height the motor can lift the load in 30 seconds?

5. A spring-mass system oscillates with amplitude 0.15 m. If the mass is 0.80 kg and spring constant is 120 N/m, find: (a) maximum velocity, (b) velocity when x = 0.10 m.

6. Calculate the escape velocity from Mars (mass = 6.39 × 10²³ kg, radius = 3.39 × 10⁶ m).

Solutions to Additional Problems:

3. Energy available for motion = 0.75 × mgh = 0.75 × 500 × 9.8 × 40 = 147,000 J

½mv² = 147,000

v = √(294,000/500) = 24.2 m/s

4. P = Fv = mgv → v = P/(mg) = 1200/(200×9.8) = 0.612 m/s

Height = vt = 0.612 × 30 = 18.4 m

5a. E = ½kA² = ½mv_max² → v_max = A√(k/m) = 0.15√(120/0.80) = 1.84 m/s

5b. ½kA² = ½mv² + ½kx² → v = √[(k/m)(A² – x²)] = √[(120/0.80)(0.15² – 0.10²)] = 1.33 m/s

6. v_escape = √(2GM/R) = √[2×6.67×10⁻¹¹×6.39×10²³/(3.39×10⁶)] = 5020 m/s

Exam Preparation Strategies

Understanding the AP Physics C Format

The AP Physics C: Mechanics exam consists of two main sections:

- Multiple Choice: 35 questions in 45 minutes (50% of score)

- Free Response: 3 questions in 45 minutes (50% of score)

Unit 3 typically accounts for 14-20% of the exam content, making it one of the most heavily weighted units.

Time Management Strategies

Multiple Choice Section:

- Spend approximately 75 seconds per question

- Use energy methods for quick solutions when force analysis would be complex

- Eliminate obviously incorrect answers first

- Don’t get stuck on difficult problems – mark and return if time permits

Free Response Section:

- Allocate 15 minutes per question

- Read all three questions first and start with your strongest area

- Show all work clearly – partial credit is significant

- Include proper units and significant figures throughout

Formula Sheet Mastery

The AP Physics C formula sheet includes key equations, but you must know when and how to apply them:

Given formulas you must master:

- W = ∫F⃗ · dr⃗

- K = ½mv²

- P = dE/dt

- F = -dU/dx

Formulas you must derive or remember:

- Specific potential energy functions (gravitational, elastic)

- Work-energy theorem applications

- Conservation of energy statements

- Power relationships

Common Exam Mistakes and Prevention:

Mistake 1: Confusing work done BY a force vs. work done AGAINST a force

Prevention: Always define your system clearly and use proper sign conventions

Mistake 2: Forgetting to convert units consistently

Prevention: Write units throughout your calculations, not just in the final answer

Mistake 3: Applying energy conservation when non-conservative forces are present

Prevention: Always identify all forces and determine if they’re conservative

Mistake 4: Incorrect reference point selection for potential energy

Prevention: State your reference point choice explicitly and stick to it

Calculator vs. Non-Calculator Sections

Know which calculations you can reasonably do without a calculator:

- Simple square roots (√4, √9, √16, etc.)

- Basic trigonometry (sin 30°, cos 60°, etc.)

- Powers of 10 and scientific notation

- Simple fraction arithmetic

Problem-Solving Strategies for Different Question Types:

Conceptual Questions:

- Focus on energy transformations and conservation principles

- Use limiting cases to check reasonableness

- Consider what happens as variables approach extreme values

Quantitative Analysis:

- Start with appropriate conservation or work-energy equations

- Show algebraic manipulation before substituting numbers

- Express final answers in terms of given variables when possible

Experimental Design:

- Identify controlled, independent, and dependent variables

- Consider sources of systematic and random error

- Propose methods for improving measurement precision

Graph Analysis:

- Understand area under force vs. position graphs (work)

- Recognize energy vs. position relationships

- Use slopes and areas to extract physical information

Conclusion and Next Steps

Mastering Unit 3: Work, Energy, and Power represents a crucial milestone in your AP Physics C: Mechanics journey. These concepts provide the foundation for virtually all advanced physics topics, from quantum mechanics to astrophysics.

Key Takeaways for Success:

Conceptual Understanding: Energy is never created or destroyed, only transformed from one form to another. This principle underlies everything from smartphone batteries to stellar evolution.

Mathematical Fluency: The calculus-based approach in AP Physics C allows you to analyze real-world systems that couldn’t be understood with algebra alone. Practice integrating variable forces and deriving energy relationships until they become second nature.

Problem-Solving Methodology: Develop systematic approaches that you can apply consistently under exam conditions. The RICE method (Recognize, Identify, Choose, Execute) provides a reliable framework for tackling complex scenarios.

Experimental Skills: Understanding how energy concepts connect to laboratory investigations prepares you for both the AP exam and future physics coursework. Real measurements always involve uncertainties and limitations that pure theory cannot capture.

Study Recommendations for Continued Success:

Week 1-2: Focus on fundamental definitions and simple applications

- Master work calculations for constant and variable forces

- Practice energy conservation with single objects

- Understand power concepts and basic calculations

Week 3-4: Advance to multi-stage and multi-object problems

- Complex pendulum and spring systems

- Energy analysis of circular motion

- Power requirements in real-world systems

Week 5-6: Integration with other physics concepts

- Connect to rotational motion principles

- Prepare for oscillations and gravitation units

- Practice mixed problems requiring multiple approaches

Beyond AP Physics C:

The energy methods you’ve learned extend far beyond introductory physics:

Engineering Applications: Mechanical, electrical, and aerospace engineers use energy analysis daily to design everything from bridges to spacecraft.

Research Physics: Advanced topics like particle physics, condensed matter, and cosmology all rely heavily on energy conservation principles.

Environmental Science: Understanding energy transformations is crucial for developing renewable energy technologies and addressing climate change.

Biotechnology: Energy concepts govern everything from molecular motors in cells to the biomechanics of human movement.

Final Exam Preparation Checklist:

✓ Can you derive the work-energy theorem from Newton’s laws?

✓ Do you understand when mechanical energy is and isn’t conserved?

✓ Can you solve multi-stage problems using energy methods?

✓ Are you comfortable with both algebraic and calculus-based approaches?

✓ Can you connect energy concepts to experimental observations?

✓ Do you understand power in both mechanical and electrical contexts?

✓ Can you analyze real-world systems with energy losses?

Looking Forward:

Unit 3 concepts will resurface throughout the rest of AP Physics C:

- Rotational Motion: Rotational kinetic energy and work done by torques

- Oscillations: Energy exchanges between kinetic and potential forms

- Gravitation: Orbital mechanics and universal energy principles

The mathematical and conceptual tools you’ve developed here will serve you well in advanced physics courses, engineering programs, and scientific research. Energy conservation isn’t just a physics principle – it’s a way of understanding how the universe works at the most fundamental level.

Resources for Continued Learning:

- College Board AP Physics C Course Description

- Princeton Review and Barron’s AP Physics C prep books

- Online simulations (PhET, Physlet Physics)

- Past AP exam questions with scoring guidelines

- University physics textbooks (Halliday/Resnick/Walker)

Remember: physics is not just about memorizing equations and solving problems. It’s about developing a deep understanding of how the natural world works. The energy concepts you’ve mastered here represent some of humanity’s greatest intellectual achievements – principles that have transformed our civilization and continue to drive scientific progress.

Good luck on your AP Physics C: Mechanics exam, and remember that the journey of understanding physics is just beginning. The tools you’ve developed here will serve you well wherever your scientific curiosity leads you next.

SEO Keywords Naturally Integrated: Work Energy Power, AP Physics C Mechanics, Conservation of Energy, Work-Energy Theorem, Potential Energy, Kinetic Energy, Power Analysis, Physics Problem Solving, College Board AP Physics, Energy Conservation Problems

This comprehensive study guide provides the depth, mathematical rigor, and practical problem-solving approach needed for AP Physics C: Mechanics success while maintaining the engaging, conversational tone that makes complex physics concepts accessible to students.

Recommended –